In the 90s, work took me to New York enough that there was a time when I at least knew the pizza scene (which never impressed me that much) and the deli scene (far better; I never came back without a swing by Zabar’s) and a few other things. But kids came and suddenly leaving one big city to visit another made a lot less sense, so I actually had not been back to New York since, I think, 1998. (That’s me, waving the Statue of Liberty good bye with a bag of lox and bagels under my arm.)

But I had to go there for an award recently, as you may have heard here, and I decided to drag the whole family along. Of course, the big question was, what to eat? Except for deli, maybe, I felt completely out of the scene (is Luchow’s still around?) Needless to say, it was essential that I maximize my time in NYC to the utmost, eating exactly the things most different and unique from whatever I eat here. Expertise in about 10 meals total, that was my goal.

On the other hand, I wasn’t there to drop the big wad and eat fancy-schmancy; why spend college tuition at Per Se when you haven’t even been to Alinea here at home yet? So first off, I wanted a couple of nice, not too expensive meals. The kind of meal for which, in Chicago, I would have suggested Mado a year ago. Which made me think, who better to ask for a Mado-like recommendation than not-that-long-ago-New-York-line-cook Rob Levitt, at The Butcher & Larder?

“We’re always happy at Lupa,” Rob said in his laconic way. So that was dinner our first night, and you know what? I will always be happy at Lupa from now on, too. I get the feeling some New Yorkers consider this longtime entry in the Mario Batali empire to be a bit past its prime, but I couldn’t disagree more— this is the laidback neighborhood restaurant par excellence, as good a meal for around $200 for four as I’ve had anywhere. Warm and inviting, but with an Italian menu seriously devoted to doing great and authentic things and not being afraid of offputting ingredients.

I loved a pasta with bottarga, the slight fishy-brine cast it had. Myles had a flank steak that he declared the best steak he’d ever eaten. Glazed carrots, snap peas with mint and wild mushroom, bacalao turned into an awesome piece of panko-crusted fried fish, a delicately jiggly panna cotta with pineapple soaked in something… everything was simple, superbly executed, singing of its fine ingredients and no froufery.

Rob’s other recommendation that we took, Peasant, was more problematic. On paper it seems a Madoesque no-brainer— simple direct-from-farmer ingredients prepared in a woodfire rotisserie or the like, letting the clean flavor of the ingredients shine.

And things were prepared beautifully— in the sense of being cooked exactly right, to the perfect texture and consistency. The problem was, most of it was just kind of bland. I couldn’t help but think that at Mado, they would have found the sprig of something while it was cooking or the twist of something as it was plated that would have taken it to the next level, but nothing here seemed quite sharpened in that way. Starters were very good— one of burrata and tomatoes, one of calamari in wine and vinegar— but after that, seemed to lose their way, with a pizza of nettles and ricotta, roasted pig, roasted sea bass, and two desserts all kind of lacking something.

And the restaurant seemed to be lacking something, too. That shot of the guy next to the oven may look like your dream of buon’ Italia, but the dining room itself was weirdly cold and a bit unwelcoming, with those damn aluminum Navy chairs from the Design Within Reach catalog, dim lighting (and absurdly tiny type on the menu), a chill in the air I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Service was pleasant but distant— a kind of dipping oil arrived, for the fish I think, and there wasn’t so much as a word about the fact that you might actually want to use it for that purpose (where it helped the fish enormously). Compared to our warm embrace in the bosom of Lupa, this wasn’t one to treasure and remember— and measure Chicago by.

Those were our two high-end meals (my third was at the Beard Awards) but we ate many cheap eats things gleaned from Chowhound and the like, and even I didn’t have this soup dumpling or that pizza like I’d hoped, I felt very good about how many different bases we touched in a very short time and the extremely high batting average of what we ate. Arriving around noon, I needed a place near our Times Square hotel, and if there was nothing great near there that I could find, the diversity of choices along Hell’s Kitchen’s Ninth Avenue strip was pretty exciting. We grabbed our first lunch at Empanada Mama, whose empanadas range from classic to Hot Doug’s-esque (I liked the seafood-based Viagra Empanada; my 9-year-old loved the peanut butter and banana Elvis Empanada). Only an arepa, with which you could have won a Stanley Cup, disappointed. (We would have a much better arepa at an otherwise okay roasted South American chicken place called Farmers Rotisserie Chicken.)

The much better arepa from Farmers.

I heard that Zabar’s had a cafe now, so for breakfast before the American Museum of Natural History (good new dinosaur exhibits, some unique things, but overall I’d give the Field the nod, especially for having more spacious dinosaur halls and much better direction/signage), we popped in there. Turns out the cafe is basically aimed at getting commuters in and out; they won’t really make you a bagel and lox fresh, and point you to a refrigerator case where a premade bagel and lox is sitting there getting cold and rubbery.

Not the refrigerator case in the cafe.

I did not return to Zabar’s after close to 15 years to have an experience like the cafeteria in a highway rest stop. Quickly, I figured out how to force a decent experience that would work for breakfast with no means of, say, spreading cream cheese. I ordered the requisite number of bagels, fresh, sliced, with cream cheese. We took them and then I went next door to order lox by the pound. Here, instead of the impersonal rush of the cafe, we enjoyed the full Zabar’s experience, the deli guys sweet-talking 85-year-old ladies and Dominican nannies in their inimitable way (“Dolling, have some sable, just for you I cut this because you’re so beautiful”). It’s one of my favorite places on this earth, for me the essence of what the big city, the urban and urbane, deeply Jewish big city I read about in Mad promised to a Catholic kid in Kansas. I have been away from you too long, Zabar’s, but I have never forgotten you. We put our ethereally supple belly lox on our bagels and sat in the park watching dogs go by. It was one of the best breakfasts I’ve ever had.

The high end burger craze has hit New York like everywhere else and Danny Meyer’s Shake Shack seems to be the one that everyone has fallen in love with. I hadn’t planned to make a special trip there, but when we came out of the museum at about 12:15 and it was right there on the corner, well, the logic with two kids in tow was pretty much inescapable. Maybe we just hit them at an executional off moment, but I was not overly impressed, which is to say, sure, it’s better than hitting a fast food burger, but— you know how somebody will tell you that Oklahoma City finally has a really great French restaurant, and you know it wouldn’t be make the top 50 in New York? Well, the reverse is true, too, with hamburgers. My handformed burger was medium, if medium means the average of one charred side and one nearly raw one; even more strangely, the shakes were not really cold enough and kind of runny. (I will give the deeply crinkly cut fries high marks, though.)

Oh, and one other thing, they say they have Chicago style dogs, but the dog itself is nothing like a Chicago dog— and neither is cutting it in half and frying the insides.

On the other hand, a place that did live up to every bit of its hype was Doughnut Plant. I confess to doubts as I stood in its very slow line and prepared to pay $2.50 per yeast-raised doughnut, while our reservation at the Tenement Museum (fascinating, terrific, reserve your tour in advance) creeped closer. But all doubts went away when we bit into the toothsome, almost brioche-substantial yet light and chewy doughnuts. The creme brulee doughnut, at $3.00 for a small little ball with an admittedly excellent custard inside and a crisp crust on top, seems more like a gimmick, but the straight up doughnut was worth every penny of its ridiculous price, assuming that you’d pay $2.50 for what might well be the best doughnut you’ll ever have in your life.

Doughnut Plant was, truth be told, our second breakfast that morning; the first was a newly opened little place we spotted just down the street from our hotel on 49th between 8th and 9th called Donna Bell’s, a Southern bakery with things like crusty drop biscuits. Not sure I’d go a long way out of my way for them, but we certainly enjoyed finding something so down home Southern in the middle of Manhattan, and they seemed very eager for us to enjoy their products.

With two breakfasts in tow and dinner at Peasant not that far away, we just needed a snack for lunch. I had printed out this Chowhound guide to a post-Tenement Museum Chinatown tour, and took the first advice on it: chive dumplings at tiny, grungy Prosperity Dumpling, along with two orders of scallion pancake (more like focaccia, but whatever), for a whopping $4. These would be great cheap eats anywhere but especially in Manhattan, wonderfully flavorful dumplings fresh off the wok and swimming in grease. Yum!

NYC Chinese food was something I wanted to sample, and so was Japanese food; since my meal at Sankyu, especially, I’ve been really interested in trying Japanese places that offer something other than the typical American-Japanese restaurant fare. Unfortunately, with so many of them hot tickets to get into (like Ippudo for ramen), I didn’t have much hope of being in the right place at the right time with family in tow and patient enough to put up with the wait. (For the same reason, I didn’t even mess with the whole Momofuku empire and the gyrations required to get into any of its places.)

But after the Beard awards, the group I was with (Reader editor Mara Shalhoup’s Atlanta friends, mostly) suggested that if everybody wasn’t completely full, maybe we could pop by for a late snack and drinks at Yakitori Totto, a popular Japanese bar-restaurant located on a second floor in Midtown which I had jotted down as one I hoped to try… yes I said yes I said yes. It took a lot of standing around and phoning other restaurants while we waited, but thankfully none of them could take us and Yakitori Totto finally did and so, at midnight, we placed a hurried last call order and sat down with, in my case, a shochu-yuzu jam cocktail.

Most of the food comes from a tiny grill where a single cook keeps flipping skewers— everything from the expected pork and chicken to shisito peppers and something made from ground rice turned into a sticky ball on a stick. Add a couple of bowls of fantastic savory congee-type porridges and this was a great meal in a kinda hipster, kinda divey late-night atmosphere. If there was a place like this in Chicago I’d become an alcoholic just to hang out there every night. Or a yakuza.

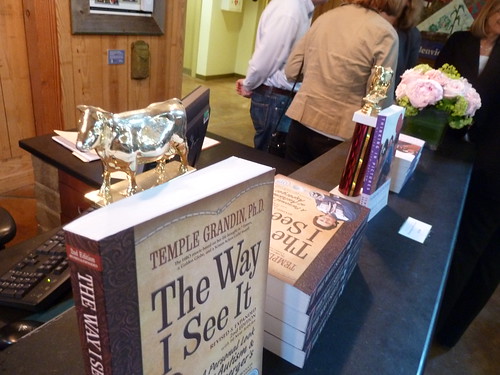

Finally, one of the places I was absolutely going to visit, no matter what, was Russ & Daughters, legendary for its sturgeon. Even if it was Mother’s Day, and Sunday morning, and it was going to be absolutely packed:

I left the kids outside to fend for themselves with a couple of black and white cookies; taking a cue from the Tenement Museum the day before, they immediately declared themselves to be orphaned street urchins. But they were still there when I came out, and hadn’t joined the Dead Rabbits or some other alley gang, so I guess everything was okay.

Now, Russ & Daughters is famous for sturgeon. It was good, the lox was good, but I didn’t love it more than Zabar’s. The sturgeon, in particular, seemed like it didn’t quite have the meatiness of sturgeon I’ve had elsewhere. A nice place, lots of character, but Zabar’s remains my love.

Except… I never had the sturgeon.

I think. I just discovered this looking at their website. What we ate as “sturgeon” had a distinct orange cast from seasoning (paprika?) on the outside. I don’t see that here, on the sturgeon. But I see it here… on the sable. I’m 98% sure that he cut me sable, not sturgeon (and hopefully charged me the sable price).

Jesus, now I have to get nominated for another Beard award next year and have the sturgeon.

So, fantastic eating in four days, covering the globe from South America to Eastern Europe to Japan. Several things that were arguably the best of their genre that I had ever eaten, or top 5 material at least. Does that mean New York is better than Chicago? I don’t think of it that way; both are capitols of eating. But what it does show is how you can zero in on the really great stuff in a distant city these days, thanks to the internet and all the food content on it. That’s why we all do this stuff, that I was lucky enough to win an award for.

Posted in

Posted in