Note: if you’re here for the map showing you how to get to Ciya Sofrasi, scroll down till you see something that looks like… a map.

* * *

We arrived in the afternoon— Christmas Eve, though there was little to remind us of it— and the taxi took us to our hotel, a square three-flat on a steep hill facing an ancient city wall… as well as facing a tumbling wooden shack in front of which sat a brand new Toyota. Dark was coming quickly and when I went out to find somewhere for dinner, I took pictures of the turns I made so I could follow my pictures back to our hotel. With drizzle constricting my vision and twisty streets unmarked by street signs and only rarely lit by lamps, it didn’t feel like one of the major cities of the world— it felt like Tibet or something, one of the barely-reachable places, like the village ten thousand feet up where Indiana Jones finds his old flame Marion running a bar.

Even feeling lost and damp, though, I was taken in by the twisty streets and the low-level do-a-little-of-everything commerce, like the Lower East Side in the 20s or something. I quickly saw places I wanted to try to eat at— if I could find them again. Our first meal wound up being in a restaurant run by a Kurd, and it set the pattern for many— it took about ten seconds to have the proprietor or someone else talking English to us and telling us a fractured, semi-comprehensible story of his time in America doing something on behalf of some relative who had some business here, in amid parenting advice, famous Americans they knew of, and every other subject that could come up. Turks, we quickly learned, are as friendly and chatty as the Irish, and they seem to badly want you to like their country.

I hoped I could find this charcoal kebab place again.

The meal also set the pattern for meals— every meal, it seems, is grilled kebabs, rice, and bread. Pointing them all out would be like telling you where to get a Coke in America, so I’ll stick to the more interesting and anomalous ones from here— in particular, the restaurant that everyone seemed to know because it is the one Turkish restaurant that isn’t like all the others. It was a pleasant and welcoming evening… even as I held private doubts as to whether we could stand a week in such a remote and claustrophobic place.

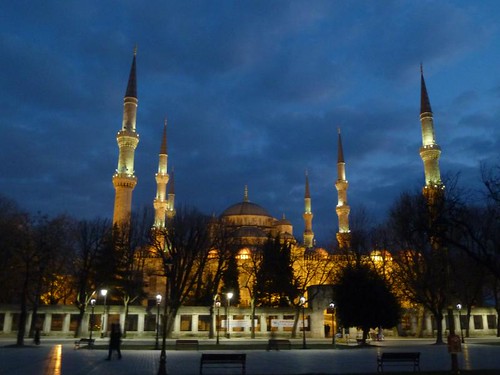

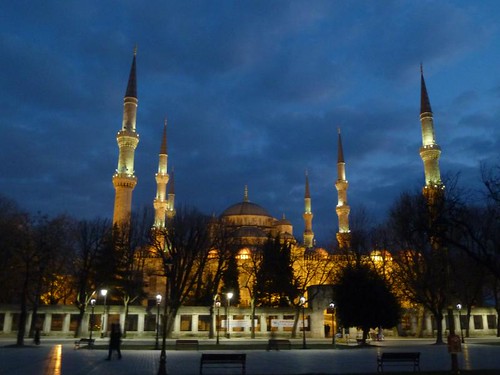

The next morning the rain was gone, the sun was shining… and Istanbul was beautiful, bright blue sky, dark blue sea, clean air (surprisingly little car traffic in this part, actually), a white city by the sea that could not have been more gorgeous, and my love was cemented. It was also, though we rarely thought of it, Christmas. We allowed ourselves to be seduced by a hotel at the south end of the Hippodrome and paid $15 a person for a breakfast buffet, not worth so much for what we ate (yogurt, dried figs, a croissant) but worth twice that for the view from the high point of Sultanhamet of the sea just a few blocks away— and the impeccably old world service by waiters who looked and acted like they were in a Poirot mystery on PBS.

Istanbul is the third largest city I’ve ever been to, after LA and New York (and much larger than Rome which preceded it), but it’s not a place people think of as a natural destination— to judge by the number of people who went “Hmm, why Istanbul?” when I told them about going to Istanbul and Turkey generally. Even if you’d think of going to there yourself, you might not think of it as an interesting destination for your kids. Yet it was all of that, and what’s more, one of those instantly enticing, vibrant and welcoming and youthful cities that always reminds me of Dr. Johnson’s line “If one is tired of London, one is tired of life.” That is what cities are— a grand bazaar of possibilities— and where I left Rome thinking “checked that one off,” I left Istanbul wondering how I’d get back.

The call to prayer, heard from a side door of Hagia Sophia.

Of course, part of it is that the tourist part of Istanbul hardly seems to belong to a city of that size; the area from Topkapi Palace to the Hippodrome is like Central Park in Manhattan, a rare open expanse in a city of crowds and twisty streets. By the numbers the “real” Istanbul is surely the rapidly growing, only moderately urban-planned areas outside the old city, the could-be-anywhere Blade Runner sprawl of glass skyscrapers and cell phone shops that you see stretching out forever as you go up the Bosphorus. The 2000 years of civilization before that are just baubles around its edges from the water. But hey, I visited that Turkish Blade Runner and thought it was pretty fascinating, too.

I’m still not crazy about Turkish desserts, especially anything with rose water.

The logical place to stay for a tourist is in the Sultanahmet neighborhood adjacent to the main tourist attractions (and convenient enough to most anything else). As it happened, technically we were in it, realistically we were below it, facing the exterior of the ancient city wall on its south side— and that would prove to be a good thing.

The hotels in the more touristed and populated area are probably fine, but the restaurants (in a strip right by Hagia Sophia and the Sultanahmet tram stop) tended to be the sort of mediocre, overpriced places that cater mainly to Australians and English looking to get drunk and rowdy; not surprisingly our worst meal and our most expensive one were one and the same, and in that area. (Islam’s prohibition on drink seems to be unknown to Turkey, which not only has bars but breweries and wineries.) Leaving that area and entering the claustrophobic twistiness was nearly always a better idea foodwise, and in time I came to love it too.

We spent Christmas day at Hagia Sophia— hey, I actually went to church on Christmas, for once— and then taking a two-hour Bosphorus ferry cruise, but at night we returned to our neighborhood and I tried to scout out some of the things I’d discovered walking around the night before. To my joy I found again the little shop where they were grilling kebabs over charcoal in the window— if one must have kebabs, these were the kebabs to have—

I found it again!

and then another where they made pizzas— or something pizza-like, though instead of round, the Turkish style seems to be a few inches across and literally two feet or more long. I returned clutching these prizes and this was our Christmas dinner.

The Spice Bazaar.

Sultanahmet has two famous bazaars, and what I’d heard before we went was that the Grand Bazaar was a vast tourist trap, while the smaller Spice Bazaar was more accessible and interesting. Yes and no. It’s absolutely worth it to go through the process once of being sold spices by a fast-talking salesman overwhelming you with bright colors and smells, and we came back with lots of vacuum-packed spices. That said, the Spice Bazaar is kind of, done one spice stand, you’ve done them all.

We went to the enormous, disorienting Grand Bazaar early in the morning when it was least crowded, which undoubtedly made it easier to like, but as full as it is of silly knickknacks, knockoff designer goods, Nike t-shirts and who knows what all (I went in in just a sweater, and was immediately descended upon by guys convinced I was there for a leather sportcoat), it’s also a place where you can find someone with a shop full of early 20th century tin-plated kitchen pots, surely as good a collection as any history museum in Turkey, and learn more than you ever dreamed about it in 10 minutes from the owner. Like Istanbul, the Grand Bazaar is life in all its clamoring variety, so vast and endless you suspect it must contain some sort of time-space distortion that allows a whole city to fit within a single building. I enjoyed roaming it and the markets extending around it for blocks immensely and would happily do more of it— early in the morning.

The markets continue all around both Bazaars for blocks.

Though honestly, you won’t have a bad meal by simply picking the nearest neighborhood kebab spot that doesn’t look totally discofied for tourists, the monotony of this dining could get to you after a while. The source for online intel on Istanbul eats is a blog called Istanbul Eats, and following their suggestions led us to the two best places by far that we ate at— which also happen to be the two places we ran across that had recently had major articles about them in New York-based media; funny how that works out, isn’t it.

The first was Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi, featured some months back in the New York Times. Doner kebab— the lamb stacked on a cone which is common enough in Chicago middle eastern restaurants, and basically the same as gyros— is everywhere, grilling in the usual doner machine. What’s not common at all— apparently unique in Istanbul in fact— is the pre-industrial version of the same thing, cag kebabi, in which the lamb is stacked by hand, the roll is roasted next to a fire and the pit master shaves off pieces for you, taking care to select meaty bits, fatty bits, charred bits and tender bits according to some algorithm only in his own head.

We ate there twice and did the same thing both times— we each ordered the standard two skewers, with a tomatoey red sauce, salad, a bowl of water buffalo soft cheese, and a big piece of floppy flat bread. Then, when we were done, we ordered two more pairs of skewers and shared them between us.

I used the word pit master advisedly because the care the owner, Ozcan Yildirim, takes makes him brother to any barbecue pit master, to anyone with a love for meat over fire, cooking anywhere in the world. When my kids think of Istanbul, I’m pretty sure the first picture that comes to mind is this:

Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi

Hocapasa Sok. 3/A, Sirkeci

212-520-3361

The other place worth calling out is not as immediately lovable as Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi, but offers more depth— which is why it got a lengthy piece in The New Yorker instead. Owner Musa Dagdaviren might best be described as the Rick Bayless of Turkey, though instead of finding traditions in a neighboring country, he finds them in the much less cosmopolitan east of Anatolia, bringing traditional home dishes to restaurants for the first time. He’s serious enough to have started a scholarly journal about traditional Turkish food, and when he finally publishes a cookbook, it will change the world’s perception of Turkish food (hopefully Phaidon will translate it as they have with other big national cookbooks). Traveling outside Istanbul among other Americans and Europeans later in the trip, we found that nearly everyone had heard of Ciya Sofrasi— because in a country of meat skewers, it seems to be the only restaurant serving vegetarian dishes. (His original restaurant is alleged to be vegetarian— which doesn’t stop lamb from turning up here and there. He also has a kebab place across the street.)

If you find this, you’re standing in front of Ciya Sofrasi.

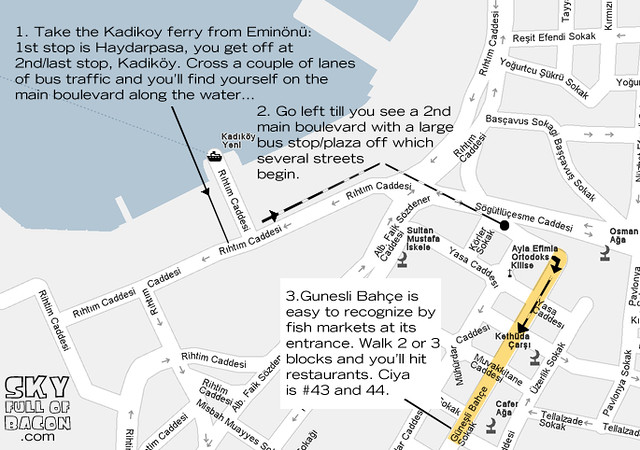

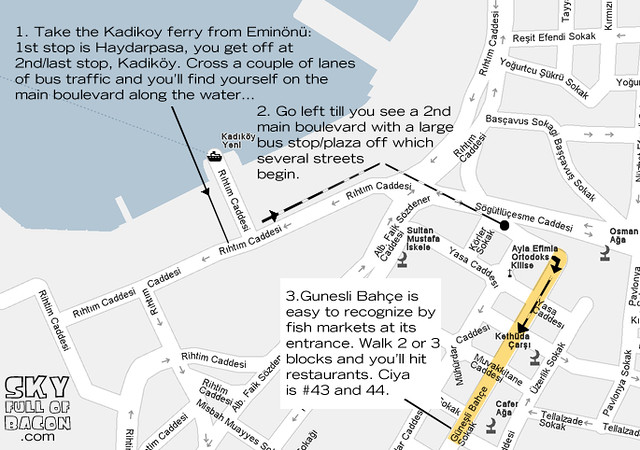

Heard of Ciya Sofrasi, I should say, but found it hard to find. Ciya Sofrasi is on the Asian side, in a district called Kadiköy, near the Haydarpasa train station which is where, once your journey on the Orient Express terminated on the European side, you would arrive by ferry to continue on to… India? Siam? I don’t know.

Haydarpasa. You stay on till the next and final stop.

Anyway, Kadiköy is very much the modern Blade Runner place I was talking about, cell phones and skyscrapers and busy markets, and except for the ferry terminal none of it was on our map or indeed any map I could find. Even the best written directions I got took a couple of tries to match to reality, which is why I decided to put this map online to make it easier. You get off the ferry, cross the street to another cluster of bus stops…

look for the street that is full of fish markets, and start walking. After many fascinating markets…

You will hit a patch of restaurants, all of which will try to lure you in, American, Ingleesh? Very nice menu for toorists.

Keep walking and eventually you find…

There’s no menu you could likely read, but the food is all laid out behind glass. Just point and point and sit down and they’ll bring it to you. Don’t try to choose, don’t look for a certain dish as they change a lot, just point.

Salads; the thyme salad in front seems to be a particular favorite.

No idea what this was.

The stews all kind of look like this, but they’re different.

This leek-based one was my favorite.

Candied fruits for dessert.

Musa Dagdaviren is on the right. I don’t think he understood a word I said, but I hope he understood that it was genuine admiration.

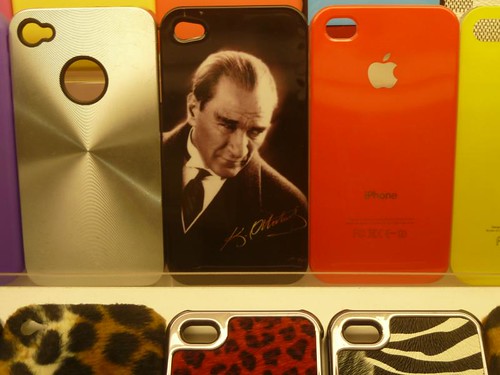

In some ways they’re all very similar, and it’s not that there are lots of different flavors that jump at you, their satisfactions are those of things well stewed together. But here and there one thing will leap out, and they’re all as satisfying as soul food, and a break from kebabs for a night, for no more than about $1.20 on the ferry. Make your way back through the markets, consider whether you really need an Ataturk cover for your iPhone, and go back by the next ferry. You’ve been to Asia for dinner.

Ciya Sofrasi

Guneslibahce Sokak 43, Kadiköy, Istanbul

902163303190

http://ciya.com.tr/index_en.php

Whenever we saw this portrait of Ataturk, it prompted (very quiet) jokes about “the father of our country, Bela Lugosi.”

* * *

Cappadocia is the sort of place where they set up a wood-burning spiced wine stand next to a 600-year-old limestone city.

We spent a few days outside of Istanbul in Cappadocia (home of strange limestone formations and houses carved out of them, as seen in the original Star Wars), and Pammukale (home of other strange limestone formations that look like Antarctica, and a nice Roman amphitheater).

We went on tours arranged by this company, located right by the Sultanahmet tram stop, and while I’m generally firmly against tourbus travel, it was the only sensible choice here for this remote country and I recommend their services wholeheartedly. The tours were small (usually a 14-seat bus 2/3 full) with a guide who was engaged with the subject and happy to talk about other aspects of life in Turkey; while the home base took care of everything (including an itinerary change from the road) without a hitch. (Turkey, incidentally, has inexpensive regional airlines with brand new fleets, so we flew the long distances, very reasonably.) There is the usual shopping stop during the day, but of high quality (a pottery workshop, an onyx factory), and a lunch stop at some restaurant which was never spectacularly good but turning out pleasant enough homestyle food in an atmosphere of camel tapestries and swords on the wall that could have been anywhere from Morocco to Mongolia, seemingly. (The only thing I might say is that two days of limestone formations in Cappadocia might have been a bit much; if you want to cut it shorter, pick the one day in which you get to see the deeply creepy underground Christian city. To have come to that, literally a religious community burying itself alive in a hole in the ground, from the staggering worldly splendor of the Vatican a few days earlier is to get the most visceral feel possible for Christianity’s journey in the world over the millennia.)

The food in central Turkey— setting aside that it was truly winter at that elevation, where it had been fall in both Rome and Istanbul— was much more like things I’ve had in Georgian or Armenian restaurants than the meat-focused kebab cuisine of Istanbul, consisting mainly of simple stews and carrot-based salads. That said, I can tell you an infallible way to have a good meal in Cappadocia, even in the emptiest, most desperate for tourists time of the off season: look for a wood burning oven. If they have it, they’ll be making the stew inside a clay pot, which is a better show than a dish (they crack the tops off at the table; they’re sealed with dough):

but also they’ll be making pizzas, again, two foot pizzas. I’m not a huge fan of the Turkish basturma, the air dried pastrami-like meat which is very sharp tasting, but if there’s anything to be done with it, putting it on a pizza is it. And especially with kids, who were not inclined to be happy with a lot of vegetables or a plate of cold manti, no matter how much their father insists they’re just like ravioli (no they’re not, they’re cold and covered in yogurt), a Turkish basturma pizza is a godsend.

* * *

Dandurmas, with some kind of syrupy yet also stretchy topping.

Although I dissed Turkish desserts above, there was one we had just briefly on our last day (splitting a single cup between the four of us) that led to an amusing coincidence. It is maras dandurmas, a kind of ice cream made with orchid flour which makes it weirdly stretchy in the same kind of way that a lot of molecular gastronomy hydrocolloids do to food. After we got back I was shooting the new Key Ingredient, with Brandon Baltzley, and he mentioned (as you see in the film) dandurmas. But the film doesn’t show the exchange that followed right after:

ME: I just had that three days ago.

BALTZLEY (giving me an are-you-shitting-me look): Really? Where?

ME: Istanbul.

Sometimes life works out strangely neatly. So I’ve tried dandurmas twice in my life, on two different continents… in the same week.

Posted in

Posted in