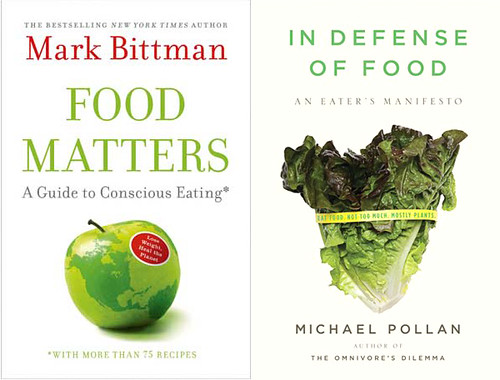

Mark Bittman is a New York Times writer and the author of some highly useful cookbooks which bridge the gap between real cooking and modern lifestyles. So Food Matters: A Guide to Conscious Eating seems at first as if it might be a more practical (“With More Than 75 Recipes!”) version of Michael Pollan’s food-system polemics like The Omnivore’s Dilemma and In Defense of Food (the cover of which it especially resembles):

It certainly starts out like the work of a New York Times writer:

Two years ago, a report from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) landed on my desk. Called Livestock’s Long Shadow, it revealed a stunning statistic: global livestock production is responsible for about one-fifth of all greenhouse gases—more than transportation.

Unfortunately, the New York Times writer this mainly sounds like is Thomas Friedman, whose standard breathless lead-in was mocked recently by Matt Taibbi: “I was in Dubai with the general counsel of BP last year, watching 500 Balinese textile workers get on a train, when suddenly I said to myself, ‘We need better headlights for our tri-plane.'” Everything about this paragraph throbs with self-importance: the report didn’t come in the mail, it landed on his desk at the Times, with an urgent thud (“Bittman! Friedman! I need global greenhouse gas statistics— that means now, ladies!”) The report doesn’t contain, it reveals a statistic, which stuns Bittman (though it shouldn’t be that surprising to a leading food writer that modern agriculture uses a lot of fossil fuels). And all that’s just in the opening paragraph. At this rate, by the third chapter he’ll be spraying cranial fluid every time a carrot arrives in his inbox, demanding action.

Indeed Bittman soon reveals that his is no mere feelbad meditation on food, but an actionable diet plan with truly planetary consequences. And not just in the sense that yo’ mama so big, when she rubs her legs together, it makes global warming:

If I told you that a simple lifestyle choice could help you lose weight, reduce your risk of many long-term or chronic diseases, save you real money, and help stop global warming, I imagine you’d be intrigued. If I also told you that this change would be easier and more pleasant than any diet you’ve ever tried, would take less time and effort than your exercise routine, and would require no sacrifice, I would think you’d want to read more.

He might think that. You might be thinking, how do I get away from this relentless huckster before I wind up with a timeshare in Florida and a complete set of ShamWow?

Cutting through the hype, Bittman’s basic premise is that if we eat less meat and more greens, the pounds (and the planet) will take care of themselves. Eating less meat may seem a simple choice, but only in the sense that “Stop drinking” and “Relate to hot girls as people” are simple choices, too, which often prove devilishly difficult to carry out. Eating less meat is no sacrifice only if you find Pan-Cooked Greens With Tofu and Garlic (p. 211) every bit as satisfying as steak. The change is easier and more pleasant only if you have the time to devote to learning new ways of meal-planning. And so on. It’s not that these things aren’t true, possible or undeniably beneficial, it’s that Prof. Harold Hill keeps selling us on all the fabulous benefits of having a band while gliding over any mention of the need to practice.

Most of all, there’s that reference to global warming. I expect publishers have been trying for years now to find a way to make global warming into a diet book, thus bringing two of today’s hottest trends together, and Bittman does valiant work in connecting the dots between industrial agriculture and global warming. Again, it’s not that any of this isn’t true, necessarily, it’s that it’s hyped so breathlessly to make this the most important, most impactful, most earthsaving diet book in the history of mankind:

Could improved health for people and planet be as simple as eating fewer animals, and less junk food and super-refined carbohydrates?

Yes.

Helpful tip: never answer “no” to the question “Is it really this simple?” in Bittman’s book. For baby boomers, who can turn any personal choice into an issue of planet-sized portent, it’s no longer enough to lose weight to save your arteries or your sex appeal; only the prospect of rescuing an entire celestial body will keep you away from the donut cart.

To be fair, having pounded the podium into organic mulch in his first few chapters, Bittman does tone it down in in the next 100 pages or so, with a more temperate run-through of our present food system that will be familiar to Pollan readers, especially those of In Defense of Food. Familiar, that is, but not comparable in its impact or interest— Bittman does essentially none of the reporting Pollan does, never taking us to meet food scientists or feedlot operators; he’s saving the planet without leaving his desk. (He even explicitly prefaces a section on factory farming by saying he’s going to “skip most of the deplorable stuff,” as if dramatization would get in the way of self-dramatization.)

Nor is his account as well organized as Pollan’s critique, flitting about semi-randomly from topic to topic as long as every factoid he flings supports his general thesis. That opening statistic about agricultural greenhouse gases returns at the end of chapter 2 as if we’d never heard it before; every activity is reduced to its measure in fossil fuels consumed—as if efficiency alone weren’t a numbers game that industrial agriculture is destined to win.

And not to sound like I’m shilling for the American Michael Pollan Council, but in contrast to Pollan’s coolly incisive dissection of the problems, Bittman’s anger often runs ahead of his grasp on logic:

It doesn’t take a genius to see that an ever-growing population cannot continue to devote limited resources to produce ever-increasing amounts of meat, which takes roughly 10 times more energy to produce than plants. Nor can you possibly be “nice” to animals, or respectful of them, when you’re raising and killing them by the billions.

Like a soy burger, this looks like it has the meaty fiber of an argument, but crumbles at the first touch of a fork. Set aside the sloppy writing (that first “produce” should surely be “producing”), and it’s a logical muddle: how much meat is taking 10 times more energy to produce than what plants, the meat we eat now or the ever-increasing amounts? And is it the killing or the numbers that make raising meat not nice? Are we talking my individual niceness (hence the second person), or society’s (hence the billions), which are presumably two different forms of niceness? A fiery but confused paragraph like this doesn’t exist to inform, it exists to keep you wound up enough to keep turning the page. Bittman is to Pollan on nutritionism what Dan Brown is to Graham Greene on Catholicism.

Okay, but even if Bittman’s book is a clip job, doesn’t it serve a purpose if it calls more attention to the very real problems in our food chain? I think not, because the lack of nuance in Bittman’s account extends not only to the problems but to the solutions. Because ultimately he’s writing a diet book, which is to say a book preaching hope and salvation for those who follow the one true path, he ignores and even flatly contradicts himself on the sticky dilemmas that Pollan wrestles with.

Pollan recognizes that food prices will have to go up to support better forms of agriculture. But Bittman preaches that you’ll be saving money in no time (and his factoids have food prices shooting up in one chapter and falling, thanks to industrial efficiency, in the next). Bittman pushes buying less meat as a way to reduce the impact of meat on the planet, but never considers the irony that that’s likely in the short term to increase the market share of industrial meat, as the conscientious people support their local farmers less and the unconscientious ones buy 48-packs of lamb chops at Sam’s Club.

Which leaves only the second half of the book, the recipes. How are they? They look all right, in a Mediterranean-diet-with-a-touch-of-Asian kind of way. The breakfast and lunch ones are simple and pretty attractive; there’s no question that Bittman has a genuine knack for idiot-proofing contemporary flavors so that the harried, not-all-that-culinarily-skilled yuppie can turn out something respectable that matches modern tastes in a fairly short amount of time.

The dinner ones are more problematic, because they look less like a change from anything anyway (when Bittman suggests a 40-minute cassoulet containing a pound of sausage or pork chops, he’s not making a healthful cassoulet, he’s just mucking up a classic dish with bad technique), and because many of them are too vague to really help the cook who has no clue what to do with a kohlrabi or a squash. Telling people they can use any old vegetables they want in a stir-fry isn’t likely to be news to them, and it isn’t likely to lead to terribly good stir-fries, either.

And that’s the problem with what ought to be the most useful part of this book: there’s not enough depth to it. Are 77 recipes, even ones that teach basic skills, enough to put my family and the planet on an entirely new basis for eating? It seems unlikely.

To put the comparison in Bittmanesquely reductive terms, at a shipping weight of 1.2 pounds per book, a case of Food Matters uses as much fuel (according to calculations that just landed on my desk) as a 733-mile road trip. Deborah Madison’s Vegetarian Cooking For Everyone weighs in at a much heftier 4.3 pounds, which is as much oil as 3.6 sperm whales, but it contains over 1400 recipes, making it approximately 20 times as efficient to take those sperm whales on a road trip. Can it really be this simple, that if you want to take Bittman’s advice, you can get all you really need of it from this review and then spend your money more wisely on a comprehensive vegetarian cookbook like Madison’s— or, indeed, Bittman’s own How To Cook Everything Vegetarian? Yes.

Posted in

Posted in