Chicago has been such a booming, wealthy city for so many decades that entire eras of its past have been almost wiped out— the wedding cake-Victorian Loop obliterated by the imperial classicism of the 1920s; the cheesy modernism of the 1960s hanging on only in ungentrified suburbs. But just when I’m regretting the obliteration of great chunks of our past, I remember that there’s a city not far away where they survive unselfconsciously. Milwaukee has been prosperous enough all these years that it hasn’t fallen into disrepair, like Detroit, yet at the same time it hasn’t boomed with the force of an atomic bomb, the way Chicago sometimes seems to have. A trip last Saturday with a small group of LTHers to visit an artisanal meat-curing facility was also a chance to travel back in time to several pasts much harder to find traces of in Chicago.

The first stop was Bolzano Artisan Meats, who I’ve posted about before here. Bolzano is Wisconsin’s first cured whole-meat producer (ie., things like prosciutto, rather than sausages), and owner Scott Buer offers “Charcuterie School” to a small group each weekend, in which he explains the basics of how he makes his products. (You can check it out here.) Since we were, so to speak, advanced students who’ve mostly made charcuterie ourselves at some point, we skipped the class and went straight to the factory tour.

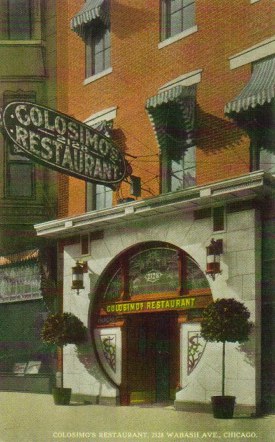

I knew Bolzano was located in the former home of Great Lakes Distillery, which I imagined to be some 19th century brick factory in a rapidly gentrifying area of lofts and nightclubs. Turns out it was actually a streamlined 1950s facility in purest Industrial Moderne originally built as a Sealtest dairy, including the former laboratory, armored around with sturdy industrial tile:

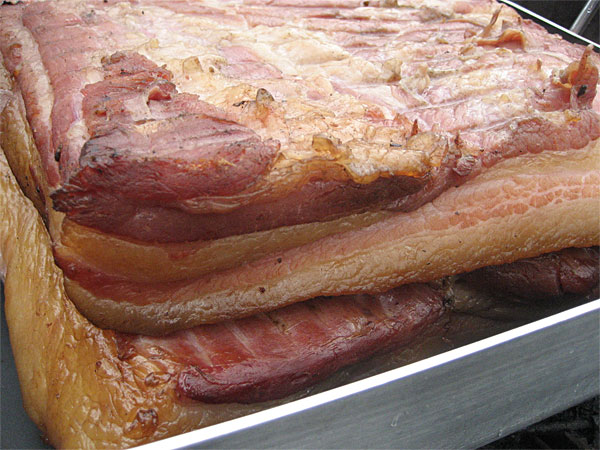

—all of which gave “Charcuterie School” even more of a high school feel than I’d expected at first. The refrigerator cases and smoker are all located in a larger, gleaming white room. The first walk-in is for meat that’s been cut up and salted (or will be shortly):

while the second is for things hanging and drying out:

There’s also a little shop open on weekends, where you can pick up their goods.

Scott told us how the business has evolved since he sent me his first products some months back. He’s now working with whole hogs, which since he doesn’t make sausage, has necessitated some creativity in terms of his product offerings; he’s invented some of the cured products he’s offering, such as Suslende, which means sweet loin and is simply a cured loin with some maple syrup added to the cure. It also requires managing refrigerator space carefully, when you have a products, prosciutto, which takes nine months; it would be easy to fill the fridge with hams and then have nothing to sell for most of a year, at which point you would go bankrupt before anyone got to try any of those hams.

He also told us about the regulatory hurdles he had to overcome. Fortunately for him, since he’s mostly dealing with the state, who are at least vaguely supportive of agriculture-related businesses, he was able to find at least a certain level of cooperation in exploring this uncharted territory, and wasn’t caught in the Catch-22 of “nobody’s doing it, therefore there are no rules, therefore it can’t be done,” as Chicago food businesses have been lately.

One change that’s unfortunate, if understandable, is that he’s about to switch to only selling sliced product; he’s had too much trouble with people who buy chunks and then can’t cut them properly and come back, looking to get their product sliced. But I like dicing the pancetta and guanciale from larger than the paper-thin slices, so I stocked up on those in chunk form during this trip, and recommend making your reservation for charcuterie school and picking up a little of everything at their store soon.

Our next stop was the new home of Great Lakes Distillery. They give tasting tours on the weekend, but since we arrived late and it’s all in one room anyway, we just listened to the tour and went straight to the tasting. They’ve made everything from bourbon to pumpkin brandy, much of which has sold out quickly, so on this day we got to try a straight and flavored vodka, a very floral gin (not sure how this would mix— I guess there’s one way to find out!— but I liked it a lot), some fruit brandies (the pear, which has a really nice real-pear aftertaste, was by far the best), and finally, two absinthes:

One is a straight green absinthe, the other is called red from added hibiscus, though it’s actually clear. This latter seemed odd to me, too floral, but I’m sure it has its uses. The green absinthe seemed very good, and about half the price of others I’ve seen, so that’s what I came home with, though whether I’ll ever get to making it in the traditional way (as opposed to using in sazeracs, say) is questionable. Anyway, another great and welcoming experience, I’d certainly recommend this as well.

Next up were a couple of abortive attempts to connect with Milwaukee’s old Italian heritage in the Brady street area. We arrived at Glorioso’s, Milwaukee’s best-known Italian deli, just as they were closing, but did note that they’re about to move into a bigger building across the street, so will have to visit them before that happens. Another more mysterious stop was Dentice Bros., an Italian sausage supplier which Peter Engler thinks may have gone out of business (the owners being quite elderly). Yet when we found the shop, everything looked as if they had just closed up five minutes earlier— and really, it is often hard to tell between a 100-year-old business that’s still around or one that’s preserved in death like a museum display. So who knows?

What was still in business after 100 years was Kegel’s, an old German bar and restaurant where it could easily be 1890. There are others like this in Milwaukee, such as Mader’s and Karl Ratzsch’s, but they depend on the tourist trade to no small part; Kegel’s, on the other hand, feels like it’s still serving a thriving German neighborhood clientele, and the idea that it’s picturesque hasn’t really occurred to it. We had a beer and two orders of pork shank rolls, another example (like Mader’s reuben rolls) of the odd Milwaukee tendency to take bits of Germanic meat and roll them up in eggroll wrappers and deep fry them. I have to say, they went with the dark German beer very happily.

Kegel’s, however, was merely an appetizer before our main dining event, Maria’s, which comes close to the platonic ideal of the old school pizza joint— located in a building that looks like somebody’s 50s ranch house, decorated on the outside with world-class neon and plexi 60s signage, and on the inside with a mixture of paint-by-religious paintings and the usual sports geegaws, while a staff of mostly family do what they’ve been doing forever.

Zaffiro’s has a reputation on LTHForum as the Milwaukee old school pizza, and it’s a fine one, but Maria’s easily surpassed it as the one I’m jonesing to get back to right now; I loved the burnt-edged, crispy cracker crust, the simple tomato sauce topping, the sausage bright with fennel. As far as I’m concerned, it’s about as good as an old school pizza joint experience gets (though I could tell the one Easterner in our group, still under the spell of Pepe’s in New Haven or whatever, was the less enchanted one among us).

We ended the night with another temple of neon, Leon’s, for custard. Again, LTHForum has anointed Kopp’s among Milwaukee custard emporia, but Leon’s seemed just as good, and it certainly had the 70s-brutalist Kopp’s location in Brookfield beat. By this hour it was quite chilly out, but that didn’t seem to have stopped anyone from standing in line for custard cones, and it was a fitting end to our travels through many pasts in Milwaukee.

Posted in

Posted in