Usually program notes for stage productions all sound alike; your actors have a nice list of serious credits for Remains or the Goodman along with some minor scattered TV roles on Chicago-shot shows like ER or Early Edition. Then there’s the notes for Cascabel, where the past roles are more likely to have been Vegas, Cirque de Soleil, or some strange fringe carnival troupe… not to mention the guy who’s apparently never appeared in anything, other than his own TV series about cooking in Mexico.

Mike G’s Rule holds that if there’s a reason to eat somewhere besides the food (ie, a view, waitresses in skimpy outfits), the food’s most likely not that good. Cascabel, co-conceived by and starring, sort of, Rick Bayless, seems to invent a theater corollary to that— if there’s a really good chef’s food in a play, the play itself is probably not much. Cascabel has a wisp of a plot about a mysterious cook and a boarding house whose female owner has a secret sorrow, cobbled out of Like Water For Chocolate’s cookbook for mixing food and erotica, with a hearty dose of broad Latin stereotypes— but like in a play about a famous bunch of musicians, you can’t judge it by too stringent terms, it’s there just to bridge the numbers. Of which Cascabel has two kinds: Bayless’s food, and the cast’s acrobatics.

The acrobatics are great, nervy fun, insofar as most of them are performed over the heads of at least a few audience members and could, conceivably, kill them if they went wrong, a fact that even the well-muscled performers of both sexes can’t shed enough clothing and grind lasciviously enough to entirely make you forget. One performer changes clothes standing on a clothesline tightrope, leaving you genuinely wondering how much of his shakiness and near-missing is actually acting; a couple doing an erotic dance wind up not only using bananas in the obvious sexualized way, but shooting chunks of banana from one mouth to the other, and catching nearly every time. At their best, which happens pretty frequently, the acrobatic numbers are graceful or thrilling or just plain funny enough that they blast past erotic-review cheesiness and achieve something of the “magical realism” the story aims for.

Then there’s the other kind of “number” this show has— the food of Rick Bayless, who is on stage for almost the entire play, cooking for the cast (and given that he is pretty much nose to the grindstone, no phony flourishes the whole time, you believe he really is cooking). After a couple of appetizers and a complimentary margarita, the meal has three courses, eaten at the same time as the cast eats it and is transported to new realms (several feet in the air) after a few bites. The first and best by far was a tuna ceviche with a passionfruit flan, all the gloriously tart citrus flavor of Mexican seafood (I even loved the pre-show popcorn snack that sat with it and soaked up a little of its limey flavor). The second is the inevitable hunk of red meat, a compromise nod to those audience members for whom every meal must have a big piece of protein even if Mexicans generally don’t eat like that: a ball of filet in a mole with a tamale and some braised kale. (Given that my favorite Bayless recipe to make is his swiss chard tacos, I’d have been happy with less red meat and more greens.) Finally, a bright pink cake of Oaxacan chocolate with a blood orange mousse on top, which is good but not so obviously Mexican. I’m sure it’s the best meal I’ve ever eaten at a play, if not the most interesting meal I’ve ever eaten from Rick Bayless.

All in all, it’s a good meal and a broadly enjoyable show, though the fact that the play has to stop cold for both kinds of “numbers” only emphasizes the thinness of the underlying dramatic material; there might be thirty minutes of dialogue in this 2-1/2 hour show, and by the time they’ve hit the wine pretty good, a lot of the audience is barely aware when there’s a show going on on the stage at all, only paying attention when it’s going on above it. I might have wished for a real playwright to flesh out these archetypes during the dead time when audience and cast are eating. I also might be the only one who was thinking about that as well as of the carnal pleasures on display, on stage and on plate.

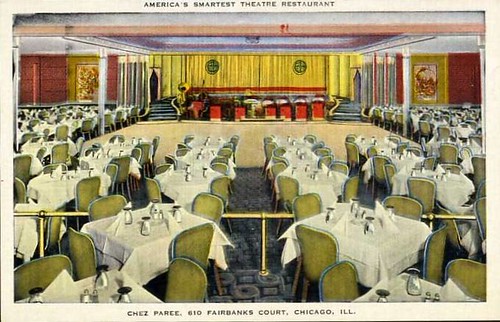

At the end, happily, the cooks in back come out to join the cast for a bow, and are warmly appreciated by the audience. Will there be more Cascabels? I’m not sure how many chefs can really act even to the degree that Bayless does, though it does have me suddenly contemplating shows they could do (Paul Kahan and Donnie Madia as Nathan and Sky in Guys and Dolls?) I doubt we’ll see many more shows of this type— much easier for the chef with performing ambitions to just be on TV— but as at least one other restaurant is proving right now, there is an audience for a dinner that tells a story and puts on a show as much as it satisfies hunger, as surely as there was 60 or 70 years ago when the floor show of dancing, acrobatics and girls was as essential to dining out as the food.

Posted in

Posted in