I fretted before our trip to Japan, because here was a chance to dine in one of the world’s greatest food cultures, perhaps my only chance to sample certain things—sushi, wagyu beef, etc.—at their absolute peak. So the clock was ticking, I had to get it right! And picking outstanding restaurants to go to was difficult; it quickly became clear that there was a fairly small set of restaurants talked about by westerners, and a vast iceberg beyond that (Tokyo, famously, has over 100,000 restaurants, and that’s not hyperbole—TripAdvisor lists 82,724 of them). In the area of sushi in particular, for instance, the ones known to the west—led of course by the famous Jiro—were booked up weeks if not months in advance.

So an agonizingly drawn-out process began of soliciting recommendations from people who knew the scene pretty well—including Steve Plotnicki and Yukari Sakamoto, author of Food Sake Tokyo, which also came recommended by both Steve Dolinsky and the Momotaro cook Scott Malloy, who I wrote about for the Reader. They would give me names; I would email my hotel, because you generally cannot make reservations yourself but must go through a concierge or other service; and somewhere around 48 hours later, I would find out if anything had room for us at any time.

Now, let me give you the good news: you kind of don’t need to do any of that. Well, you might for sushi. We ate sushi twice, and there was as obvious a quality difference between the two experiences as between a fine dining restaurant and a diner—which indeed is pretty much what each of them was, and fine in its own way. If you want that high-level experience, which we managed to have, finally, at an up-and-coming sushi temple called Sushi-Ya, you’ll need to do some research and make some plans.

But I’m not so sure I’d do it for anything else. I don’t regret our other high-end, quite pricey experiences, but I don’t know that I think any of them was that necessary, either. The caliber of the food culture is so high that you could just walk into anywhere in the more popular parts of town, just based on what sounded good, and have a great experience. I mean, almost nothing disappointed. We picked an udon place once in Kyoto where the broth wasn’t that great, but even there, the tempura chicken on top was as good as any I ever had in my life. Hell, even at Starbucks we had something that was fantastic—a canteloupe Frappucino with chunks of fresh canteloupe in it.

This is how Japan eats.

And there’s one other advantage to not messing with reservations much—the Japanese, for all their efficiency, have never accepted that street signs and address numbers would help tourists (and themselves). Most of our reservations involved getting somewhere close to the place with the help of our phones, and then standing outside, desperately scanning buildings for some clue as to where what we wanted might be. A stressful start to an expensive meal.

In the end, we stayed in a hotel (Citadines Shinjuku) near the action, though pleasantly a little away from the center of that busy area with its giant department stores and Blade Runnerish red light district, and around the corner from our place was a nice strip of modest restaurants which seemed to have one of everything—ramen, teppanyaki, a breakfast spot, Chinese food, Italian food, and so on. And it was much more pleasant to simply decide what we felt like, and walk two minutes to it, and give it a try—and it was always good. If you go to Tokyo, I recommend doing it that way—it’s cheaper, easier, and makes you feel more at home there.

* * *

And yet, we were still close enough to mad, mobbed central Shinjuku that we could walk in ten minutes to Takashimaya, the great department store. Whose basement food halls are like Food Disneyworld, and overwhelming in their color, their variety (not just Japanese food but everything; we went there a few times for French pastries to eat the next day), and how beautifully they’re presented. Anya von Bremzen has an excellent piece that explains sociologically why and how the department store basements, or depachika, have come to be such temples of gastronomic delights:

To a Westerner these subterranean food halls seem less like places to buy-and-bite and more like mammoth hyperdesigned exhibition spaces devoted to the latest food trends. And it isn’t just the profusion (an average food basement stocks some 30,000 items). The thrill of being at a depachika these days is the sense of riding the crest of the Japanese shopping mania, marveling at the virtuoso layering of the ritualistically traditional and the outrageously outré, of handmade and high tech. If Japan is the mecca of global consumerism, depachika are its newest shrines to excess.

Von Bremzen’s insights are well worth reading but, like a lot of Disney sociological insight, you’re not necessarily going to have more fun in the moment by thinking about it critically rather than just letting yourself go with the flow of sheer sensation. In the supermarket part there’s a guy tending clams in rushing water as if he were at an aquarium and wagyu beef marbled like an Italian palazzo and candies and spices and teas of every color. There are stands for yakitori, and Chinese food, and shimmering cakes and stained-glass-like custards and jellies. In multiple trips to Takashimaya as well as one to nearly-as-nice rival Isetan, I was always exhausted, overstimulated like a sugared-up three-year-old, before their wonders were exhausted for me.

Prepared meals in a bag.

We ate a lot of these. Basically chocolate rolls a la cinnamon rolls.

Indeed, not counting breakfast at the hotel, our first meal was entirely stuff we picked up at Takashimaya, bento boxes of this and that. One question, though—where do you eat it? Not, it turns out, at Takashimaya—there’s no seating (though there are separate restaurants some floors up). Generally people seem to picnic at the nearby park, though as it was spitting rain, we just ate back at our hotel.

Sushi-Ya, which literally means, “Sushi Place.”

Delicately thin chives inside a slice of fish.

That night, for the first and only time to date in a foreign place, we left the kids on their own. Ramen is easily their favorite Japanese dish, and there were two ramen places on our little restaurant row, so we gave them money to pick one and order for themselves. Meanwhile my wife and I took the subway to Ginza to find Sushi-Ya, which turned out after much phone-mapping to be in an alley (with no English signage)—never mind that everyone dining there was an English speaker from another country (such as Singapore).

I could tell what everyone was because it’s an 8 seat restaurant. This is part of the charm, certainly, and one we’re just starting to adopt in the U.S., the tiny dining space where you’re up close and personal with the chef and your fellow diners. I would like to report that the intimacy meant we all made friends and I have new pals in Singapore, but honestly, it was awkward as well as charming, a hushed experience like dining in a library; less jet-lagged, I might have worked harder at making us all convivial, but I just didn’t have it in me that night. (Next time, I go with Plotnicki.)

Baby octopi.

Anyway, the fish. I should say the crabs; the most interesting parts for me were things like a purple-skinned soft shell crab, or a hair crab salad (stuffed inside the hairy shell).

Looks brown, but it was purple.

Slightly obscene, but tasty.

All in all, it was many things we had not seen before, and very fine. The kids meanwhile wandered down our little restaurant strip and found a ramen place, ordered off the pictures, paid their own cash… and had a grand time on their trip to Tokyo, too.

So a couple of days later we met a hired guide at Tsukiji Market for a tour of the fish market. That’s Kiyoshi, our guide, in front:

Wasabi!

The famous tuna auction was hours before, but we caught a 7 am vegetable auction.

Bluefin is valuable, clearly.

So even after you’ve been to the smoke hall of Oaxaca and the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul and other things, Tsukiji is something else, acres of guys cutting up fish surrounded by markets of stalls selling everything that has anything to do with food and restaurants and everything.

Those look like… purple-skinned soft shell crabs!

One of the questions for any sushi devotee is, can you get the things that the high end sushi places in Tokyo have, or is there just a class of fish offerings so rare and so far above your puny station in life that you could never have them any other way, certainly not in America? And the fact was, we saw much of what we ate at Sushi-Ya here for sale, quite readily. Of course there’s a matter of quality, you can’t buy the same tuna from the same guy that Jiro can, but still, it looked to me like it was purple soft shell crab season, for sale all over the place, and the only thing stopping you from having that in the U.S. was knowing about it. There are surely some super-rare things—Sushi-Ya is high end, a spinoff of three Michelin star Sushi Saito, but not the highest end—but basically, everything seems to be available.

Anyway, an extraordinary place… and in November it will close and move to new, undoubtedly less atmospheric digs. We did a little noshing along the way, like this bacon-wrapped fish cake, or this noodle place (see the pic of the family slurping noodles at top):

Afterwards we stopped in to one of the little diner-like places, for sushi breakfast:

It was no Sushi-Ya, but it was fine, the rice still warm from having just been made, the staff pleasantly surprised when my kids picked out and ate their own orders.

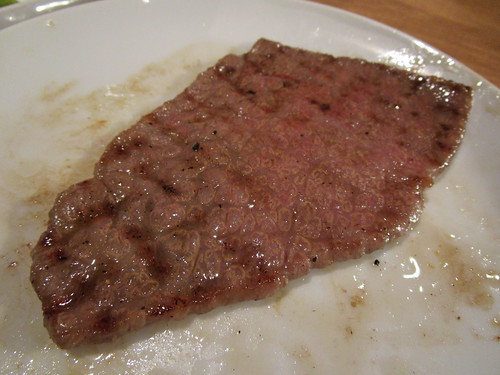

But enough of fish. There is also beef in Japan, as you may have heard. We booked two special beef experiences, which was probably one too many. One was Sumibi Yakiniku Nakahara, which turned out to be sort of like a teched-up version of Korean BBQ:

They brought us stacks of incredibly marbled meat, different cuts, and I cooked them over coals—and I could tell they thought I was overcooking them:

But dammit, you need a little actual searing or browning for the flavor, in my book. This was an all-meat meal, which was interesting as a sampler but a bit odd, a kind of stunt meal. Our other meat experience was high-end teppanyaki at a very posh place in a modern office building called Ukai-Tei:

This was quite expensive, the kind of place visiting businessmen go, very handsomely wood-paneled and so on, and the food was almost worth it. It was beautifully prepared—Susan and I actually had a tasting menu which had some exquisitely crafted things like white asparagus dotted with all kinds of modernist touches:

Though the most impressive thing on the plate, honestly, was that tomato wedge, one of the best tomatoes I’ve ever had.

And yet… I don’t want to use a phrase like “soulless” because the kitchen’s craftsmanship was excellent, the service treated us like emperors, the decor was over the top in a very refined way… but overall it gave off an air of the place Accidental Tourists go to avoid real contact with the city. This was when I thought, at the teppanyaki place down our street I could have had a meal 80% as good for 30% of the money, in an atmosphere that didn’t feel cut off from the place we were visiting. And that was more like what I was there for. So after this meal, I canceled a couple of our other reservations and resolved to just eat wherever I saw what looked good.

Instead, here’s the kind of thing we could eat for all of $12. Ramen, at the other ramen place on our street, Gotsubo, which came with a couple of nice slices of what was advertised as Iberico pork. Really? I could question that, yet without question it was very fine quality pork, and great ramen, for no more than any ramen would cost here. Which points to another bit of travel book advice you can forget. Books listed some very popular ramen places in the center of Shinjuku where you should go early and line up for an hour to get your precious seat. But I don’t believe for a second those places are measurably better than Gotsubo—they’re just better known to guidebooks. We put money in the machine to get tickets for the type of bowl we wanted, we waited maybe 10 minutes tops… and we had great ramen.

Same for tsukemen; I found a place called Gachi, located on a gay strip a few streets west (though so subtle that the kids barely knew that’s what it was), which proved to be a hipster tsukemen place, and a lot of fun. Again, maybe a 15 minute wait for thick, richly flavored tsukemen with fantastic fried chicken on top.

While in Ueno Park (home to the national art museum, well worth a trip for a quick history of Japanese aesthetic styles over time, and what the Impressionists stole from them), we went to Innsyoutei, a tea house. This was our first real exposure to the flavor of historical Japan, and the flavor of the experience went over better, I have to say, than the mostly vegetarian bento box meal did with the kids. Too many weird things in disconcerting colors.

A different time in history can be felt wandering Asakusa, another shopping area which has the feel of 50s Japan, GI’s looking for Hawaiian shirts. Indeed, one of the main strips still has its raffish black market feel as well as the modern food that goes with shopping for Levi’s and T-shirts with illogical English phrases on them—Döner stands.

In a suburb, we caught the cat bus for the Studio Ghibli museum.

Not a Disney-like theme park, the museum devoted to the filmmaker of Spirited Away and other anime films tries to instill a magical appreciation for filmmaking. You can’t take pics inside, so this is the pic everyone takes, with a robot from Laputa: Castle in the Sky.

Hachiko, Tokyo’s most famous dog, has a statue at Shibuya station. Note hat with illogical English phrase.

Liam, fitting in.

There are many treats to be had in any Tokyo train station.

Next: Kyoto

Posted in

Posted in