Click “Our Season of Pig” under Categories at right to read past installments.

The truck pulled into the gravel lot and slowly backed up to the swine barn. We held plastic barriers between the truck and the walkway to the pens, and the doors opened:

The pigs didn’t want to take that first step out of the truck, but by slapping their hams and pushing them (100-lb. girl putting all her might against 250-lb. pig), they were eventually all unloaded:

We washed them, a somewhat quixotic effort since pigs have a habit of fouling themselves just as you get them clean. The big unspoken joke of all this is that you’re competing for an award for showmanship when your animal’s idea of on-stage behavior is blithely pooping a continuous stream the whole time you’re smiling at the crowd and they’re applauding. You can see why pig-raising countries like Spain invented Dada and Surrealism.

But we got them clean enough, and set them up in their pens, decorated with pictures and ribbons. Then the kids began feeding some of them high-fat foods like cake mix to get their weight up for the official weighing-in the next day, while others (who were too close to the top of the weight class) watched and squealed angrily at being deprived.

* * *

Wednesday there were two shows— one was to judge the pigs, one to judge showmanship. Frankly, I have no idea what the distinction is with pigs; in both cases, the pigs just run where they want, and the kids chase after. (With lambs, there was at least some degree of walking them like a dog.) This was the judging among the 4H clubs; then there’s the open show judging on subsequent days. Lots of chances to get ribbons is the point, I guess.

The same judge, surprisingly not a gravel-voiced old rancher but a serious young woman, judged both. She judged six different weight classes, picking a champion and reserve champions in each, justifying her choices with language that combined cool matter-of-factness about these animals being product with a kind of aspirational language that sounded like we were trying to help them get into good schools. Her favorite words seemed to be “practical” and “everyday,” as if pigs were hairdos or sensible pants.

Liam guides Thor around the ring.

After a couple of weight classes we noticed a definite pattern— our club’s pigs usually seemed to come in dead last. I asked Julie, our club leader, why that was. She said part of it was due to our not keeping their weight up during the day of transportation and arrival; they didn’t eat due to stress and heat, and many of them lost weight rapidly. But the other part, she said, was that most of the others had probably fed their pigs Paylean, a supplement commonly used for show animals that’s basically steroids for pigs. It gives them good muscle development for the show, but the price is that it turns the meat mushy— and if you’ve eaten pork that struck you as soft and spongy, a supplement like Paylean is probably part of the reason. This is when I’m glad that, for all that we work hard and want to do well, it kind of doesn’t really matter so seriously in our lives that we’re tempted to use modern industrial-farming practices like this. If we come in last for following some principles about raising the pigs a little more naturally, that’s not so bad.

Showmanship followed and the judge hardly even seemed to look at our pigs, or our kids; we knew we didn’t meet her industrial pigs-as-product standards, and again we came in low in the group. But the kids didn’t seem to mind; it’s more about the fun of being together at the fair than it is about winning.

* * *

Friday night was the real excitement— Battle of the Barns, between the kids from all the different 4H groups. It started with a relay race including such athletic activities as running with a greased watermelon…

and running backwards around the cows.

Then the tug of war in the mud…

The adults wisely backed up once it was over, because:

When it’s over, the kids hose themselves off as best they can in the same place where they washed their pigs a few days before. Watching some of the teenagers horse around in the water, many of the older girls finding excuses to get down to bathing suits they had conveniently placed under their Battle of the Barns clothes, I couldn’t help but think that as a way to make farming cool among today’s teens, 4H is way underselling this whole coed-mud-showering thing…

* * *

Saturday was the auction. Unlike with the lambs in past years, with pigs again you just kind of chase yours around the arena.

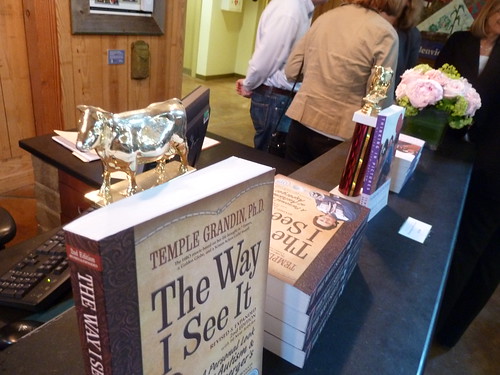

Pigs were last (after cattle, goats and lambs) so we had plenty of time to observe, happily, that prices were up again after being pretty low last year. Where cattle prices were in the dollar and something range last year, this year it was more like three dollars and something. Part of this might be that buyers are less spooked by the economy than they were last year, but part of it was also that the various clubs and the fair were making a more serious effort to cultivate buyers— there was a nice little reception at the back of the swine barn this year, complete with beer, for prospective bidders. In the end, though, our pig was sold to the same man who bought two of our lambs (and donated them to a local food bank) in past years, and we got a good price, $3.25 a pound, which means we turned a modest profit on our kids’ activity. Add in the gold star that Liam got on one of his art projects— meaning he made the short list for Grand Champion in that category— and we had a good year.

Although Myles made some comments about not shopping anywhere that bought our pigs for at least a year, in the end they weren’t bothered by a season of raising one of their favorite foods. Although pigs are more intelligent and were certainly easier to handle than lambs, they’re still kind of alien, and the kids didn’t bond with these ominously large, black-eyed (except for Frank) creatures as they might a dog. Myles even ate pulled pork at the carnival just a few hundred yards from his own pig. I don’t think this is bad in any way; only city dwellers can sentimentalize all animals as comparable to household pets. Farming has a vastly different view of livestock, and the symbiotic relationship of humans and domesticated animals is a natural thing which developed over millennia and needs to be reintegrated into our modern lives, not shunned or denied. I’m glad my kids have had a chance to discover it and understand it for themselves— including, recently, visiting a slaughterhouse and processing plant (though not observing slaughter, but engaging with it directly) for a future Sky Full of Bacon podcast. I feel I have done everything I can to prevent them from growing up to be food hypocrites, at least.

Along the way Myles said something to me which, as he sometimes does, showed a surprisingly adult perspective on his own childhood. As the summer went along and the demands of having a 4H pig got more intensive, he occasionally whined about the time it was taking up in his summer versus some imagined glorious summer of socializing as a preteen. (In reality, given that time he’d have read Harry Potter over again with his iPod in his ears.) But as Fair week approached its end, he said, “I know I’m going to complain about it sometimes, but I want to do a pig again in 4H next year. I like being part of something bigger.”

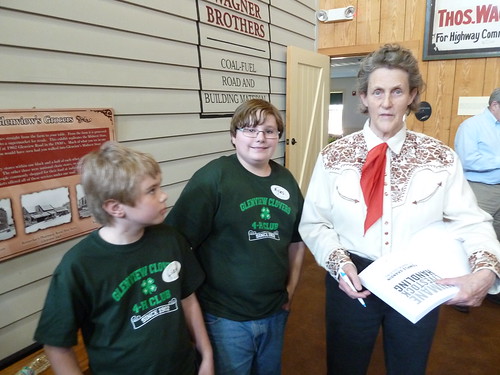

Special thanks and well wishes to our adviser, Julie Tracy, whose guidance and support during a difficult personal time is appreciated and treasured by all of us in the Glenview Clovers 4H club.

Posted in

Posted in