An old LTH friend tweeted about my Grant Achatz post and video series the week before last that it was a nice tribute to one of his culinary heroes. Yet ironically enough, Achatz wasn’t the biggest culinary hero of mine that I met, listened to or even shot video of that week. (Or, as my wife points out, the only one on the Time 100 released a few days later.)

That title would belong to Temple Grandin, and if you haven’t seen the HBO movie about her starring Claire Danes, which won a small herd of Emmys, you should. I first heard of Grandin from an Oliver Sacks book maybe 15 years ago; a high-functioning autistic with a powerful visual memory but awkward human social skills, she came to realize as a student that her form of autism in many ways mimicked the ways animals experience the world— as visual and aural stimuli which are instinctively processed as threatening or soothing, and just as instinctively reacted to. Over time, despite difficulties with human social situations, by sheer force of will and insight she conquered an ultimate man’s world— the meatpacking industry— devising new ways to handle animals humanely and efficiently on their way to slaughter by creating an environment which directs them to slaughter in a way they find calming and non-frightening. Her ideas and designs are in practice today at more than half of all US slaughterhouses.

Not everyone easily sees her work as a good thing— an anti-meat activist could paint it as deceit to lure animals to death by exploiting their instincts to imply safety ahead, and she apparently gets plenty of those— but Grandin is a powerfully blunt advocate for the notion that we owe the animals we eat a decent experience under our care, and that any notion beyond that (such as that we might all stop eating meat) is simply pie in the sky which would get in the way of being humane here and now. As she said at one point, with characteristic lack of soft-pedaling, getting killed instantly by an electric stun gun is a lot better way to die than wolves dining on live sheep guts. For her, it’s that simple— probably, again, in part because her autism focuses her on immediate, real world responses to events, not utopia.

Grandin was in Chicago for the American Meat Institute conference; she came to Wagner Farm, where my kids are in the 4-H program, for an entirely different set of reasons. Julie Tracy, who runs the 4-H program, is a communications therapist often dealing with autistics, and has an autistic son who has been in 4-H in past years. As she described it in her introductory speech at lunch, at one point when she was having a difficult time, she got to thinking about Grandin’s areas of expertise— animals, autism, communication— and decided that everything in her life coincided with them. So she called Dr. Grandin up in Colorado and left a rambling message, asking for any insight she could offer into the troubles she was experiencing. Grandin called her back within an hour to offer her insights, and was made even more interested in our 4-H program because of the problems we had experienced with animal rights protesters last year. Grandin plainly believes that getting more kids involved in 4-H is the solution, not the problem, to animal rights issues, and that protesters like we had need to be confronted head on with a positive message about the program— and, by extension, the reality of a meat-eating world and how to make it decent toward animals.

The luncheon was a private talk, largely addressed at the farmers and other supporters of our 4-H program, and Dr. Grandin requested that its content be kept private. But I don’t think I’m giving anything away by saying it basically followed her stated philosophy about the meat industry in her books, which in the Facebook and YouTube age basically amounts to— meat’s a necessity and a reality, so don’t be afraid to show the public what you’re doing… and if you are afraid to show it, maybe you need to change what you’re doing so you aren’t. Grandin is, in a sense, an industry insider, but she’s incapable of being co-opted by the industry; she’s the voice for a personal view of the ethics of animal treatment which she has forced on a vast industry by sheer force of will and intellect.

And we heard that voice, oh yeah. As good as the HBO movie about her is, just by the nature of the medium, you’re put in her perspective as she fights the industry as a young woman to be heard; you internalize and sympathize with her viewpoint as she harangues stick-in-the-mud dumbasses who screw up her solutions and get animals needlessly killed in a pesticide dip. But when she’s speaking to you directly in real life, my friend, you are the thick-headed one who just doesn’t get it yet. I don’t mean that she’s rude or contemptuous as celebrities can be, not at all— in fact, she’s a surprising advocate for old-fashioned manners and respect, and credits her somewhat strict 1950s upbringing with a big role in helping her function and be successful. (I suspect clear rules of conduct are a help for someone without an intuitive sense for the subtleties of human interaction.) It’s just… she’s the cow and your question is the fencepost that needs knocking down, I think. And she heads straight for it.

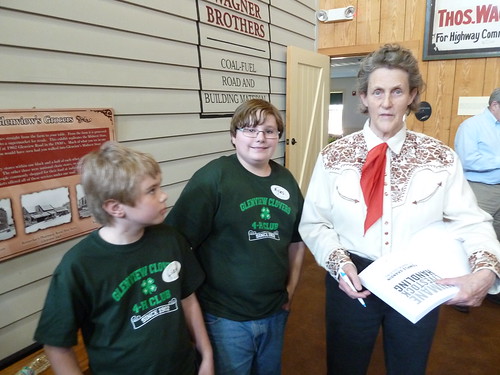

Which made her address to the kids (and the general public) afterwards all the more surprising. Having gotten used to the idea that she had one way of interacting, she was suddenly much warmer and friendlier with the kids. Admittedly, on a relative scale I’m sure she’ll seem blunt about certain realities that may seem too harsh for kids to handle (but not 4-H kids); her work, after all, is built on facilitating slaughter, and even though she was talking about how to show your animal at the fair, you didn’t long forget where she got all this insight about how to make animals do what you want them to do. But she presented to kids wanting to know how better to treat their animals in an entirely different way than she had to the adults in the meat business.

And listening to her, there’s something almost magical about her understanding of animals. We’re used to people putting human emotions into animals, every cartoon ever made has done that for us, and even the most serious-minded of animal authors, like Jack London, has been unable to completely escape putting human thoughts and feelings into the animal mind. Grandin does something entirely different— she helps us understand the animal as machine, takes the often puzzling outward signs of animal behavior and explains the syllogisms that produce them. (If A is in my path and reflecting light, I must have response B, flight.) In some ways it strips away the sentimentality of our relations with animals— and as a dog lover secretly convinced that my dog understands English and would express his devotion to me in full sentences if only he could form words with his tongue, this can be a little hard to accept. But it comes with a great gift which these kids, the dedicated and thoughtful kids of 4-H, accepted hungrily— actual insight into your animals’ behaviors and feelings. The cool logic and honesty of her explanation of animal behavior is bracing.

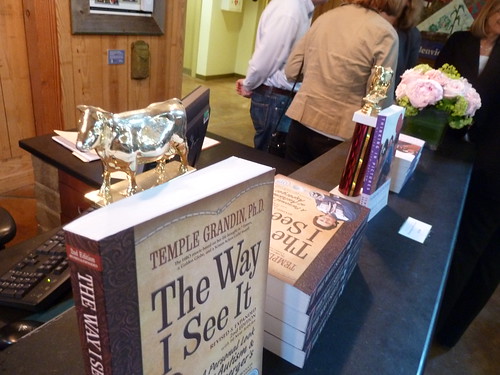

I especially liked what they used to prop up her books at the signing.

Myles gets his copy of Humane Livestock Handling autographed.

A question from the audience.

If you like this post and would like to receive updates from this blog, please subscribe our feed.

If you like this post and would like to receive updates from this blog, please subscribe our feed.