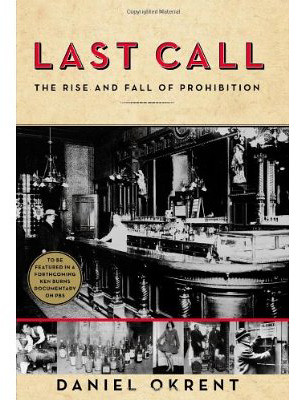

I just read a review of Daniel Okrent’s Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition which sniffed at it as being journalism rather than history. Guilty as charged; if ever there were a subject which called for a fast-paced, impressionistic and anecdotal treatment more than sober examination, it was the 13-year-experiment in telling Americans they couldn’t drink. The subject sprouts analogies like a hydra; this is the most insightful political book, the most informative book about what we put in our bodies, the most revealing book on American morals of the year, and it moves at a pace that, if it sacrifices detail (suddenly Prohibition has passed everywhere— were none of those state by state fights fascinating in themselves?), utterly fits a subject that seemed like a kind of mania that seized the country, and was undone by half a dozen other madnesses it spawned in its wake.

Prohibition came out of the religious revival of the early 19th century, but took a back seat to other moral causes (such as slavery) at first. (It was not being allowed to speak on temperance that drove Susan B. Anthony toward demanding votes for women.) A country so thoroughly drunken as the United States seemed unlikely to ever adopt such a cause, and there was never a pro-Prohibition majority in America, but by choosing to go the Constitutional amendment route (where they could assemble the necessary votes among rural states, and avoid the urban majorities of the House of Representatives), and where necessary preying on anti-immigrant sentiment against those beer-swilling Irish and Germans and the booze-inflamed Negro threat to white womanhood, they managed to eke out state by state victories. Suddenly, without the largest states and cities having had a say, alcohol was illegal nationwide, and the victorious Drys declared a new day had dawned in America, forever.

What they failed to reckon on was, simply, American ingenuity. Prohibition exploded in a million ways of getting liquor past the laws. People with boats could sail to floating liquor supermarkets just past the 3-mile limit of US legal jurisdiction over the seas, or take a new kind of vacation called a “cruise” to a Caribbean destination where rum flowed freely. Doctors issued alcohol prescriptions, drug stores opened to fill those prescriptions (and built mighty chains like Walgreen’s on alcohol profits, squeezing non-alchoholic druggists out of the business), and gentiles became “rabbis” to be able to distribute wine for ritual purposes to their supposed flocks. Great fortunes were made (the Bronfmans, but not, Okrent argues, the Kennedys, at least not nearly so much as is claimed today). The formal dinner party, with its after-dinner segregation by sex, was replaced by the cocktail party, mingling lawbreakers of both sexes who, having broken one rule of morality, didn’t stop there. The income tax was created, largely to replace the decline in government revenues caused by outlawing liquor and, thus, eliminating liquor taxes. (In a real sense, the lifeblood of government before then was alcohol.) The search power of the police was vastly expanded (including to the telephone); something called the “plea bargain” was invented to deal with the immense volume of cases.

Oh, and there was a little thing called “organized crime” that grew from a tiny scourge of inner city ethnic populations into a major, permanent feature of the economy and society, corrupting every police force that existed with an irresistible shower of money for something that, truth be told, most of them simply didn’t believe was wrong in the first place. The Maryland State House had an official bootlegger, who had to be fired when Prohibition ended. In San Francisco, the city trash service delivered California wine— and took away your empties.

It’s a marvelous story, in the sense of marveling at how so many outrageous things happened, and it’s one that is trotted out all the time as a demonstration of the futility of government legislating morality, not least in the matter of our own modern prohibition of mood-altering illegal substances. Ironically that’s the one form of Prohibition that actually did work, for a time; for 40 or 50 years after the government outlawed narcotics, they did stay pretty much out of the mainstream, unlike bootleg liquor. The lesson is, you can outlaw something that people are already convinced is wrong and to be avoided, though once they stop believing that, as people did about pot in the 1960s and 1970s, you’re back where Prohibition started.

Likewise, cigarettes could be restricted once people were against them anyway, and our modern game of replacing lard with trans-fats and trans-fats with the next fat and HFCS with something else can work as long as no one really has to make a sacrifice beyond Mickey D’s fries tasting slightly different. But get more restrictive (or bossy) and you will create a black market in Russian mafiya Twinkies overnight. And while we’re tallying up analogies, the way in which Prohibition was passed through every clever procedural maneuver known to man despite substantial voter doubt and opposition, and trumpeted as a great and permanent achievement that ordinary people would learn to appreciate in time, can’t help but remind one of Obamacare earlier this year. Health care is surely as personal as drinking, and if its restrictions come to seem too intrusive on personal choice, it is not hard to imagine that American ingenuity may sprout just as ingeniously beyond the 3-mile limit of the internet. The lesson that passing a law is not the same as having the consent of the governed has to be relearned with every generation, apparently. The only truly permanent law is the one of unintended consequences.

In Prohibition’s case, when it became (rather belatedly if you ask me) obvious to the Anti-Saloon League’s tight-leashed coalition in Congress that the law was being widely violated, they did what politicians always do— they Got Tough On Crime with something called the Jones Law in 1927, which ratcheted up the penalties for serving a single glass of hooch from speeding ticket level to felonies. To the extent it frightened ordinary barmen and druggists and rabbis out of the business, it only removed competition for the gangsters who were unafraid of any laws, and its excesses finally provoked national outrage against the pecksniffs and humbugs who’d foisted this whole regime on America and found no aspect of everyday life they couldn’t stick their noses into.

Newspapers were filled with tales of the crimes the Jones Law had led to, such as “The Massacre in Aurora,” in which a middle class Illinois housewife was gunned down in her kitchen by Prohibition agents seeking to search her cellar. Even Prohibition’s victories, like the conviction of Al Capone for violating the tax laws that only existed for the same reason he did, couldn’t stem the growing conviction that it had all been a big, naive mistake. A Wet coalition, improbably uniting immigrants (led by the likes of Al Smith and Fiorello LaGuardia) with the bluest of bluebloods (Pierre duPont, William Randolph Hearst) on the common ground of telling government to buzz off, overwhelmed the worn-out, demoralized Drys. The most effective Wet political figure, forgotten today, was probably a Morton Salt heiress named Pauline Sabin, a former Dry who came to believe that responsible social drinking among the young was better than the irresponsible binge drinking Prohibition fostered. (In a weird way, Prohibition and Repeal were both attempts to reduce the amount of alcohol consumption and the attendant social damage.) She legitimized the Wet cause among society women, and that legitimized it for everybody. And so a cause that had started with women’s newfound political power ended with it, too.

It would take five more years to pass the only Constitutional Amendment designed to completely invalidate a previous Constitutional Amendment— the Depression, and the need to restore liquor tax revenue when incomes sank, probably did the trick in the end— and pockets of dryness exist in rural counties to this day. But the idea that government could tell citizens not to drink was discredited forever on the national level (well, except for 18 to 21-year-olds, the one group that still parties like it’s 1929). And so Prohibition ended, but the types who forced it through moved on to other things to frown upon. H.L. Mencken, a vigorous defender of his own heritage of beer-drinking Germanic gemütlichkeit, described them for future generations to recognize and resist:

They cannot stop the use of alcohol, nor even appreciably diminish it, but they can badger and annoy everyone who seeks to use it decently, and they can fill the jails with men taken for purely artificial offences, and they can get satisfaction thereby for the Puritan yearning to browbeat and injure, to torture and terrorize, to punish and humiliate all who show any sign of being happy.

Posted in

Posted in