1944.

Today.

(First image snapped at the way-better-than-I-expected Cantigny Museum in Wheaton.)

|

|

1944.

Today.

(First image snapped at the way-better-than-I-expected Cantigny Museum in Wheaton.)

Before I attended the Taste of Melrose Park last year, I think I had been to that near-western suburb exactly once, to buy a couch. I don’t remember how we wound up there, but we found this furniture store where everything looked like it was designed for one of two people: Joe Pesci in Goodfellas (remember those weird buttoned collars that went on the outside of the jacket?) or Joe Pesci in Casino. (I don’t imply any sort of criminal connection, merely that Scorsese in those movies was such a fabulous anthropologist of 60s and 70s fashions among his people.) Somehow, amid all this loud taste, there was one weirdly preppy-looking couch covered, as furniture sometimes was in the 80s, with blue pinstriped ticking material. It was sedate enough— I later realized that between it and my oriental rug, basically I’d decorated my living room with a dress shirt and a tie— and so we came home with it. The couch went away a decade ago but a similar chair, to give you an idea of how my tastes have changed, was subsequently reupholstered in vintage Tiki barkcloth. Color me Pesci.

In any case, the Italian-ness, or rather the Italian-Americanness, of Melrose Park was etched in my mind. (More specifically, Sicilian-ness; that seems to be where most of the people I talked to trace their ancestry to.) And certainly visiting Taste of Melrose Park, which as a food event is basically 90% Italian-American, last year didn’t alter that point of view. What did was shooting the next Sky Full of Bacon, shortly to appear, there. As we drove there, I saw that there seemed to be more Mexican food businesses than Italian ones; but that’s true of all but the most concentrated Asian neighborhoods, any more. Plenty of Poles are eating at taquerias in Avondale; that doesn’t mean Polish Chicago is over.

But as David Hammond and I interviewed the vendors at Taste of Melrose Park, I began to realize that for many of them, this was a nostalgic event. Maybe even 20 years ago, when I was couch-shopping, Melrose Park was still the suburb that you moved to from the city. But by now the Italian enclaves in the city are virtually extinct— Taylor Street is an Italian-themed drinking strip for UIC students; Noble Square and Heart of Italy are but shadows— and the first, visibly Italian suburb families moved to from the city is beginning to give way to the second suburb, where the Italian-American community assimilates… and disappears. Melrose Park is “the old neighborhood” now, and the Taste of Melrose Park is where you come— from Naperville or Buffalo Grove or Bolingbrook— to see the people you grew up with and eat the food you grew up on. Once a year. Many of the vendors are of an age that you can imagine them moving as children to Melrose Park just after WWII; there are some adult kids working with their parents now who will likely carry it on, and there’s certainly many more happy years of this event to come, but the demographic handwriting is on a distant, but plainly readable, wall.

A little to my surprise, then, this video’s theme turns out to be strikingly parallel to my one about Lithuanian Chicago earlier this year. Lithuanian Chicago was much further along the process, but basically, the story was the same— the immigrant community near the center of the city moved to the edge (in this case, Marquette Park within the city), then dispersed into the suburbs where it is only kept alive by organizations, not by an organic community with restaurants and other commercial activity.

If more Italian-ness survives than Lithuanian-ness, the reason will likely be because of Italy’s great contribution to American culture (well, along with Columbus and Marconi, I suppose): Italian food. Lithuanian food is a very tiny specialty of food geeks like me, but Italian food’s contribution to American food is more in the nature of a wholesale takeover— not only that Italian foods are so common no one thinks of them as foreign any more, but that the Italian ethos— of seasonality and freshness and simplicity in preparation— has so influenced American dining.

That’s the thing that amazes me about Taste of Melrose Park, more than anything. Though some of the vendors are restaurateurs, many must have normal jobs selling insurance or working at the Navistar factory or… well, there’s a hell of a lot of city workers who also happen to have booths. Yet whatever they do the other 362 days a year, they seem to have almost a genetic capacity for dropping it and picking up running a high-capacity restaurant, by themselves, for three straight days in the hot sun. I mean, my family cares about food a lot, I’m merely the most extreme, but I can’t imagine us doing this competently for half a day, let alone three. Yet the Italian-Americans who run the 70+ stands at Taste of Melrose Park all seem to have a fanatic interest in food which translates into competency in serving it at this festival. Bring food up at all, and twenty minutes later they’ll still be talking about it. All of my videos are about the degree to which food matters culturally to somebody, but this one, mamma mia, it’s about a culture where it really matters, to everybody. And that intensity about food will keep restaurants alive, and the restaurants will keep the culture alive… if only as shtick in many cases, but still.

Anyway, the video will be up next week.* Unfortunately, you won’t be able to follow up on it and eat the food you see in it for about 11 more months, until the next Labor Day rolls around. But in the meantime, there is one survivor of the old Italian Melrose Park still operating on Lake Street, which was once Italian row (and is now all taquerias). It’s called Scudiero’s (they have a booth in the Taste, but I didn’t interview them). It’s a little Italian deli, with subs and sheet pizza. I stopped in on Tuesday while getting a few last establishing shots and grabbed a couple of slices; it’s not great pizza (the short crust— i.e., made with shortening— is a typical Italian-American touch that may turn off Neapolitan pizza purists, but it does last longer before getting hard in the case), but it’s simple and tastes of exactly what it is, bread, tomatoes and cheese. What do you want for a buck fifty?

Scudiero’s

2113 W Lake St

Melrose Park, IL 60160

(708) 343-2976

* Yes, I know I said the next one would be about barbecue. But that one’s gotten more complex, and this one meanwhile was simple by comparison— the shortest shoot I’ve ever done, in fact. (Two days, 4 hours of raw footage. It’s no trick to get Italians to talk.) So it got done first.

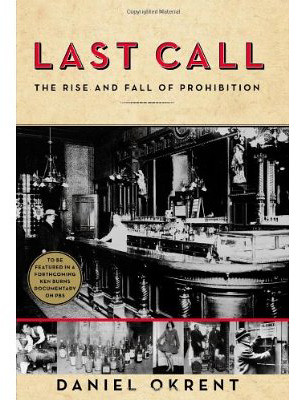

I just read a review of Daniel Okrent’s Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition which sniffed at it as being journalism rather than history. Guilty as charged; if ever there were a subject which called for a fast-paced, impressionistic and anecdotal treatment more than sober examination, it was the 13-year-experiment in telling Americans they couldn’t drink. The subject sprouts analogies like a hydra; this is the most insightful political book, the most informative book about what we put in our bodies, the most revealing book on American morals of the year, and it moves at a pace that, if it sacrifices detail (suddenly Prohibition has passed everywhere— were none of those state by state fights fascinating in themselves?), utterly fits a subject that seemed like a kind of mania that seized the country, and was undone by half a dozen other madnesses it spawned in its wake.

Prohibition came out of the religious revival of the early 19th century, but took a back seat to other moral causes (such as slavery) at first. (It was not being allowed to speak on temperance that drove Susan B. Anthony toward demanding votes for women.) A country so thoroughly drunken as the United States seemed unlikely to ever adopt such a cause, and there was never a pro-Prohibition majority in America, but by choosing to go the Constitutional amendment route (where they could assemble the necessary votes among rural states, and avoid the urban majorities of the House of Representatives), and where necessary preying on anti-immigrant sentiment against those beer-swilling Irish and Germans and the booze-inflamed Negro threat to white womanhood, they managed to eke out state by state victories. Suddenly, without the largest states and cities having had a say, alcohol was illegal nationwide, and the victorious Drys declared a new day had dawned in America, forever.

What they failed to reckon on was, simply, American ingenuity. Prohibition exploded in a million ways of getting liquor past the laws. People with boats could sail to floating liquor supermarkets just past the 3-mile limit of US legal jurisdiction over the seas, or take a new kind of vacation called a “cruise” to a Caribbean destination where rum flowed freely. Doctors issued alcohol prescriptions, drug stores opened to fill those prescriptions (and built mighty chains like Walgreen’s on alcohol profits, squeezing non-alchoholic druggists out of the business), and gentiles became “rabbis” to be able to distribute wine for ritual purposes to their supposed flocks. Great fortunes were made (the Bronfmans, but not, Okrent argues, the Kennedys, at least not nearly so much as is claimed today). The formal dinner party, with its after-dinner segregation by sex, was replaced by the cocktail party, mingling lawbreakers of both sexes who, having broken one rule of morality, didn’t stop there. The income tax was created, largely to replace the decline in government revenues caused by outlawing liquor and, thus, eliminating liquor taxes. (In a real sense, the lifeblood of government before then was alcohol.) The search power of the police was vastly expanded (including to the telephone); something called the “plea bargain” was invented to deal with the immense volume of cases.

Oh, and there was a little thing called “organized crime” that grew from a tiny scourge of inner city ethnic populations into a major, permanent feature of the economy and society, corrupting every police force that existed with an irresistible shower of money for something that, truth be told, most of them simply didn’t believe was wrong in the first place. The Maryland State House had an official bootlegger, who had to be fired when Prohibition ended. In San Francisco, the city trash service delivered California wine— and took away your empties.

It’s a marvelous story, in the sense of marveling at how so many outrageous things happened, and it’s one that is trotted out all the time as a demonstration of the futility of government legislating morality, not least in the matter of our own modern prohibition of mood-altering illegal substances. Ironically that’s the one form of Prohibition that actually did work, for a time; for 40 or 50 years after the government outlawed narcotics, they did stay pretty much out of the mainstream, unlike bootleg liquor. The lesson is, you can outlaw something that people are already convinced is wrong and to be avoided, though once they stop believing that, as people did about pot in the 1960s and 1970s, you’re back where Prohibition started.

Likewise, cigarettes could be restricted once people were against them anyway, and our modern game of replacing lard with trans-fats and trans-fats with the next fat and HFCS with something else can work as long as no one really has to make a sacrifice beyond Mickey D’s fries tasting slightly different. But get more restrictive (or bossy) and you will create a black market in Russian mafiya Twinkies overnight. And while we’re tallying up analogies, the way in which Prohibition was passed through every clever procedural maneuver known to man despite substantial voter doubt and opposition, and trumpeted as a great and permanent achievement that ordinary people would learn to appreciate in time, can’t help but remind one of Obamacare earlier this year. Health care is surely as personal as drinking, and if its restrictions come to seem too intrusive on personal choice, it is not hard to imagine that American ingenuity may sprout just as ingeniously beyond the 3-mile limit of the internet. The lesson that passing a law is not the same as having the consent of the governed has to be relearned with every generation, apparently. The only truly permanent law is the one of unintended consequences.

In Prohibition’s case, when it became (rather belatedly if you ask me) obvious to the Anti-Saloon League’s tight-leashed coalition in Congress that the law was being widely violated, they did what politicians always do— they Got Tough On Crime with something called the Jones Law in 1927, which ratcheted up the penalties for serving a single glass of hooch from speeding ticket level to felonies. To the extent it frightened ordinary barmen and druggists and rabbis out of the business, it only removed competition for the gangsters who were unafraid of any laws, and its excesses finally provoked national outrage against the pecksniffs and humbugs who’d foisted this whole regime on America and found no aspect of everyday life they couldn’t stick their noses into.

Newspapers were filled with tales of the crimes the Jones Law had led to, such as “The Massacre in Aurora,” in which a middle class Illinois housewife was gunned down in her kitchen by Prohibition agents seeking to search her cellar. Even Prohibition’s victories, like the conviction of Al Capone for violating the tax laws that only existed for the same reason he did, couldn’t stem the growing conviction that it had all been a big, naive mistake. A Wet coalition, improbably uniting immigrants (led by the likes of Al Smith and Fiorello LaGuardia) with the bluest of bluebloods (Pierre duPont, William Randolph Hearst) on the common ground of telling government to buzz off, overwhelmed the worn-out, demoralized Drys. The most effective Wet political figure, forgotten today, was probably a Morton Salt heiress named Pauline Sabin, a former Dry who came to believe that responsible social drinking among the young was better than the irresponsible binge drinking Prohibition fostered. (In a weird way, Prohibition and Repeal were both attempts to reduce the amount of alcohol consumption and the attendant social damage.) She legitimized the Wet cause among society women, and that legitimized it for everybody. And so a cause that had started with women’s newfound political power ended with it, too.

It would take five more years to pass the only Constitutional Amendment designed to completely invalidate a previous Constitutional Amendment— the Depression, and the need to restore liquor tax revenue when incomes sank, probably did the trick in the end— and pockets of dryness exist in rural counties to this day. But the idea that government could tell citizens not to drink was discredited forever on the national level (well, except for 18 to 21-year-olds, the one group that still parties like it’s 1929). And so Prohibition ended, but the types who forced it through moved on to other things to frown upon. H.L. Mencken, a vigorous defender of his own heritage of beer-drinking Germanic gemütlichkeit, described them for future generations to recognize and resist:

They cannot stop the use of alcohol, nor even appreciably diminish it, but they can badger and annoy everyone who seeks to use it decently, and they can fill the jails with men taken for purely artificial offences, and they can get satisfaction thereby for the Puritan yearning to browbeat and injure, to torture and terrorize, to punish and humiliate all who show any sign of being happy.

It must seem like a wondrous fantasy of salvation to modern journalists waiting for the ax to fall on an entire industry— a government program to pay writers to write! Alas, the 1930s Federal Writers Project was the sort of idealistic New Deal-era folly our hardened age would find too frivolous to spend money on, unlike more practical fictions such as credit default swaps or a viable American auto industry. Auto workers actually have to be paid to make cars, but as the internet has proven, writers will crank it out no matter what.

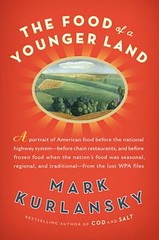

The idea of offices full of neurotic young men and women composing acres of government poetry and plays about the working man would have been horrifying, so someone had the brilliant idea of sending them into the sunshine and fresh air to gather material for guidebooks about the 48 states and various major cities. The result was the wonderful, literate, highmindedly populist WPA Guides; and when those were mostly done by the late 30s, the people still in the program were given the further task of gathering material about the food cultures of the various states. These food manuscripts were collected in Washington, and a guide composed from them was being readied to go to the printer… on December 7, 1941. After that day, other priorities took over, and according to The Food of a Younger Land, an anthology edited by Mark Kurlansky (Cod, etc.) and now in paperback, most of these manuscripts were buried like Rosebud or the Lost Ark in a box in a warehouse, until this book brought them to light for the first time…

…that is, if you don’t count the previous anthology made out of the same material, and at least one book collecting a specific writer’s contributions to the project.

So if this isn’t quite the unknown treasure trove claimed, it’s still a rich slice of one of the major food projects of the previous century, and one of the earliest records of foodways around the nation. For this foodie age, it’s not only a picture of our cuisine’s prehistory B.C. (Before Child, Julia), but a record of how people thought about food before people thought as much about food as we do, or at least in the particular way we do.

The book is, unsurprisingly, organized regionally; and it starts, unfortunately, in the northeast, a section which proves a bit colorless when it comes to food. America Eats! had already used the better of two pieces on a Vermont May breakfast, and the one that’s left sums up the boringness of the flinty Yankee palate perfectly (“Among other things served at that first breakfast was cold boiled ham”). It only comes to life in gleaming Art Deco New York, where we get a snarkily droll account of a literary tea (“If the party happens to be given in honor of a new author, he is almost always completly ignored”), and a well-observed piece on drugstore lunch counters that includes news of a new dish, hyphenated as if T. Herman Zweibel were writing, called the cheese-burger (“a doughty bit combining grilled hamburger and melted American cheese served on a soft bun and tasty enough to ensnare even the one-cylinder appetite”). Most usefully to the author of imitation hardboiled fiction, there’s an extensive glossary of classic diner slang, such as Bay State Bum (a demanding lousy tipper), Guinea Footballs (jelly doughnuts), or Two Cackles in Oink (ham and eggs).

The South, unsurprisingly, has the longest and most colorful section, not to mention the biggest names among the writers (such as Eudora Welty and Zora Neale Hurston). Many of these pieces read like fiction, or scenes from longer stories, and you can just about pick a passage at random and find something evocative of that old weird America:

The Negroes begin to gather by sundown. The host walks around barking:

“Good fried hot chitlins crisp and brown,

Ripe hard cider to wash them down,

Cold slaw, cold pickle, sweet tater pie,

And hot corn pone to sap your eye.”

(Menu for Chitterling Strut: A North Carolina Negro Celebration)

This is the part of the book that fulfills the idea of a lost American food culture, full of exotically named delights (Mississippi Mullet Salad, Georgia Possum and Taters, South Carolina Pee Dee Fish Stew) and, more to the point, a rich social dimension to how food is made and consumed in large groups. It’s also the part that truly seems to care about how you make the food; where the New England section could be frustratingly cryptic about recipes, here the detailed descriptions are loving and meticulous. It is hard not to conclude that this is the part of America where food matters, has always mattered, as more than mere sustenance.

The Midwest portion is missing some sections (Chicago, for instance, somehow vanished from the surviving manuscripts) and some of what’s left reads like parody of its food’s legendary plainness— the first piece on Kansas seems designed to convince you it’s the most boring steak-and-potatoes place on earth. There’s also a definite tendency to overwrite here, as if to make up for the drabness of the subject— Nelson Algren’s would-be intro to the section is a clumsy clip-job of the info presented in the actual pieces. And William L. White— son of the smalltown editor William Allen White, and famous for the European airs he put on after working as a foreign correspondent— affects a rowdy rusticness in the other major piece on Kansas that sounds like a city dude trying to play a tall-hat rancher.

A lot of the Midwest section is devoted to what the Indians ate before the white man, and the same is true of the Southwest section, which, as the area was pretty unpopulated, would be quite short if Southern California weren’t shoehorned in. The best of this part is a surprisingly thorough picture of the basics of Mexican-American cooking, introducing the cheese-burger’s great rival for the hearts of late 20th century Americans, “a sandwich called the taco: a tortilla fluttered through hot grease, folded around shrimp, sausage, and chili stew, garnished with shredded lettuces and grated cheese.” The remaining section, covering the west and northwest, gives just a modest preview of the impact this region would have on American dining in the postwar era, mainly conjuring up a half-lost world of plentiful seafood like geoducks and salmon. It does offer two of the quirkiest pieces; one is a three-page rant against inferior ways of making mashed potatoes, and the other is sympathetic account of the choices in industrial alcohol products available to skid row sterno bums, which reads like a parody of connoisseurship (“a new type of tippler now tops all in drinking bravado, according to Portland police. His drink is a mixture of gasoline and evaporated milk”).

Mexicans come off pretty well, and so do blacks, thanks to the regional division of the book. Otherwise ethnic cuisine is pretty much ignored, save for the occasional ringer (some Scandinavian material from the midwest, a piece on Basques in Idaho). You’ll look in vain for New York deli or Providence red-sauce Italian; this is a book about the old WASP culture. Of course, fast food doesn’t exist yet (those nascent cheese-burgers and tacos are just harbingers from the future) and there’s little mention of restaurants at all outside the New York and Los Angeles sections; “famous chef” is very nearly an oxymoron in these days.

Mostly this is a book about social gatherings, as that would be the main occasion when rural Americans (and the country was still about evenly rural and urban then) escaped a subsistence diet (like the “corn-dodger” bread described in one piece) and managed to eat, well, high on the hog. We tend to be convinced that the generation or two before us spent less time consuming media and more time interacting with people, but this book is so filled with affection for church suppers, barbecue struts, Nebraska bison roasts, police widow benefit potlucks and the like that you start to wonder, did they feel like the golden age of food togetherness had been just before their time, too? Were they regretting the time they spent listening to Amos & Andy and thinking they should have been out catching possums for a burgoo? On the evidence of this book, America has been bowling alone for longer than we may realize, and the social events that bring us together over food at its most dressed up have always been the cherished exception, not the everyday rule.

Chicago magazine has folks a-flutter (you can’t say a-twitter anymore) with a list of the 40 Greatest Chicago Restaurants of All Time. Okay, I’ll play, I’m always happy to see the past get some attention alongside the trendy. Chicago’s list is pretty much what you’d expect: three parts hot restaurants of today (Alinea, Avec) or the very recent past (Le Francais, Gordon), one part names of the more distant past whose luster still lasts (The Bakery, Henrici’s), one part nostalgia for North Shore folk who grew up on the likes of Fanny’s in Evanston or Don Roth’s.

Of course, some of this is pure hypothesizing about things we’ll never have direct experience of, like a debate over whether John Barrymore or Richard Burbage was a better Hamlet; even though a snippet of Barrymore’s Hamlet is preserved in a screen test, we can never see it with the eyes that found it revelatory in the 1920s, and we couldn’t eat at The Bakery and find it new now, either. Really, this is more like a list of the most memorable or influential restaurants, and in that sense I’ll throw out five of my own that I would replace something on Chicago’s list with.

Rosded.

Chicago’s pick: Arun’s

My pick: Thai Town

Enough already about Arun’s, a temple of overpriced Thai dining which Chicago magazine has been bowing down to for two decades. Erik M., whose knowledge of Thai food in Chicago is light years beyond anyone’s (even though he doesn’t live here any more), credits Thai Town at Belmont and Clark, in its original incarnation in the early 1970s, as the first Thai restaurant that Thais took seriously, or that took its own cuisine seriously. The owner later opened Thai Villa at Western and Winnemac, helping launch the little Thai restaurant and shopping enclave near Lincoln Square that still includes many of the most authentic and venerable Thai restaurants. Neither of his restaurants exists today in anything resembling its original form, but I suspect Lincoln Square’s Rosded, which dates to around the same vintage (and is pictured above), conveys much of the atmosphere of these prototypes of one of Chicago’s great glories of ethnic dining.

Chicago’s pick: Spiaggia

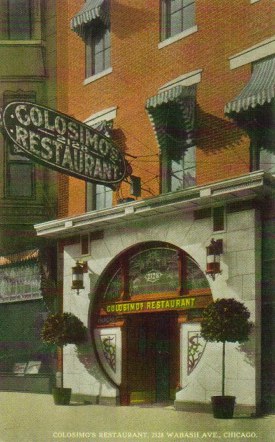

My pick: Colosimo’s

Nothing against Spiaggia, hey, I had my wedding reception there, but before anybody needed to revitalize Italian food in Chicago and return it to its authentic roots, first they had to bastardize it and give it its colorful reputation in America. And Big Jim Colosimo’s joint did just that, introducing Chicagoans to both the pleasures of hearty red sauce Italian and to the illicit delights of dining amidst mobsters, not least on the day in 1920 that Big Jim himself was gunned down in it, turning control of the nascent Outfit to Johnny Torrio, who in turn would retire and hand the keys to his young lieutenant, Alphonse Capone. (That quintessential Chicago dish, Chicken Vesuvio, is often attributed to Colosimo’s, though Rene G says there’s no documentation to support that and my bet is the dish originated at a restaurant actually called Vesuvio which was in existence at roughly the same time.) Postcards and matchbooks are worth many thousands of words here, so check out this page full of Colosimo’s memorabilia, and savor a reputation we still haven’t escaped.

Chicago’s pick: Avec

My pick: The Dill Pickle Club

Today it’s radical when guys who own a fancy restaurant go downscale and put in community seating so people might actually talk to each other, gingerly. Back when the Dill Pickle Club opened in 1916, radical genuinely meant radical, in dress, behavior and ideas, and could get you and your whole community of Wobblies, hobos, poets, slumming trust fund types and dope fiends arrested. Mainly a “little theater,” the place also had a tearoom, readings and lectures by anybody willing to stand up and take a chance, and in general was the crossroads of intellectual ferment across class lines in this rude place by the lake during the pre-Depression era. Everything Wicker Park or any other center of hipsterism wants to be, the Dill Pickle Club was. Here’s a good overview.

Rib tips, Clarksdale, MS

Chicago’s pick: Carson’s

My pick: the first guy from Mississippi to start selling rib tips and hot links on the South Side

Not having grown up here, I don’t have nostalgia for any old white people’s barbecue joint— Carson’s, Russell’s, Twin Anchors— and so I’m much more interested in Chicago’s indigenous black style, the rib tip and hot links joints that would eventually be associated with aquarium smokers. Before the aquarium smoker came to be, though, somebody was making this stuff over a 30-gallon drum cut in half in a vacant lot somewhere, for his fellow transplants from Mississippi come to seek work in the North. While he filled the air with smoke, maybe a neighbor named Chester Burnett started filling the air with blues at the same time. We remember Howlin’ Wolf; the guy who fed him, not so much, but here’s to his memory, whoever he was.

Chicago’s Pick: Ambria

My pick: Hot Doug’s

It kind of says it all that the only place actually busted under our short-lived foie gras ban wasn’t a French restaurant but a hot dog stand. Chicago honors Ambria, the place that represented Rich Melman and Lettuce’s graduation to the big leagues of fine dining in their view, when a better choice would be Fritz That’s It, R.J. Grunt’s, the beginning of the Melman empire and the jokey cartoonization of dining out that dominated our scene through so much of the 70s and 80s. But to me Melman’s conscious climb from low to high over the years is trumped by Doug Sohn, who simply saw no contradiction in putting foie gras, artisanal cheese and truffle honey on a sausage, and then naming it for someone on American Idol. He’s the godfather of all the high-low combinations that are currently one of the liveliest aspects of our dining scene— or at least the Solozzo to Bayless’ Don Vito.

[note: I thought I had read somewhere that Fritz That’s It actually predated Grunt’s, but that the Melman corporate history had been rewritten to accommodate the one that still existed and make it the official beginning of the empire. But David Hammond disputed this, and when I checked with Peter Engler/Rene G, he was quite certain that Grunt’s really was first and that Fritz actually came third, after Jonathan Livingston Seafood. Also, thanks to Gaper’s Block for the link!]

If you’re looking for something to do this Saturday night… it’s time for the annual Delafield, Wisconsin raccoon feed, chronicled in Sky Full of Bacon #9. My friend Cathy Lambrecht, who has been the Coon Feed’s leading Chicago booster and publicist, has a piece about how it all started in the north shore editions of the Tribune today; you can read it here. And here’s the video, if you haven’t seen it:

Sky Full of Bacon 09: Raccoon Stories from Michael Gebert on Vimeo.

The spat between Atlantic writer Caitlin Flanagan and the Empress of Organic Food, legendary chef Alice Waters, came to an end pretty quickly with all sorts of people running to the defense of Waters and declaring Flanagan anathema. Not since Christopher Hitchens attacked Mother Teresa has the civilized literary world reacted with such a unanimous cry of “Oooh, who farted?”

I think Flanagan raises, snarkily (it’s undoubtedly a fun read), some issues worth thinking about apart from the near-universal adulation that Waters enjoys, and I think Corby Kummer and others refute them to a considerable extent. But I think there’s an issue beyond that that no one has quite touched on— which, in the end, puts Waters in some very surprising company for an old Berkeley lefty.

Flanagan’s argument basically comes down to a single incredulous observation: So a rich white lady is telling Mexican kids they need to spend less time in the classroom and more time harvesting crops? And people think this is progress for them? She portrays Waters’ Edible Schoolyards project as a crackpot idea out of Rousseau, an anti-intellectual Cultural Revolution which is cutting into the class time they really need and wasting it on hippie notions of getting back to nature:

What evidence do we have that participation in one of these programs—so enthusiastically supported, so uncritically championed—improves a child’s chances of doing well on the state tests that will determine his or her future (especially the all-important high-school exit exam) and passing Algebra I, which is becoming the make-or-break class for California high-school students?

Now, as it happens my kids go to a so-called “hippie school” (Chicago Waldorf School), which indeed has a garden. And where they also learn things like knitting, painting, music, all that non-book stuff that there’s no room for in modern public schools. Do I send my kids there because I want them to be macrame-making airheads who don’t know which century the Civil War took place in? No, I send them there because despite spending a good portion of the day on non-academic subjects, I see that these kids, my own and their classmates, are far more engaged with the world, interested in history and politics, passionate about reading, curious about science and math, than the typical Chicago public school student. In a very real sense, they get more out of four hours of that a day than most kids get out of seven in a public school. (Kummer points out how the whole program comes out of Waters’ long-ago experience as a Montessori teacher; Montessori and Waldorf are, if not twins, certainly cousins.)

Knitting, what the school calls handwork, is the one that’s inevitably the hardest sell for parents considering Waldorf. It seems like the school day is being wasted on occupational therapy. But as the teachers patiently explain, it has all kinds of value for the rest of the curriculum, developing hand-eye coordination, inculcating self-discipline, nurturing a sense of accomplishment (people are blown away when they tell a second-grader “Nice hat” and the kid nonchalantly replies “Yeah, I made it”), even teaching math (you have to count rows and so on).

Likewise, gardening isn’t taking time from science class, it is biology. And so on. The focus and ability to concentrate and think things through and follow through till they’re done— all these things are crucial to academic subjects, and they’re developed in these non-academic pursuits. The unchallenged assumptions in Flanagan’s piece are that more and more class time in algebra would get everybody through the tests on algebra— and that the tests on algebra have real meaning in terms of future achievement, indeed, they’re the only way you’ll get there. Only if you think that the only place learning happens is a lecture hall, can you believe that it’s that simple.

Flanagan’s argument comes down attempting to paint Waters’ solution as run-amok 60s big government liberalism, what you might expect from a Berkeley free-speech lefty type:

Waters calls for a new federal program based on an old one [the Presidents’ Council on Physical Fitness], but the new one is necessary only because the old one has obviously failed: American kids are fatter and sicker than ever…

The suicidal dietary choices of so many poor people are the result of a problem, not the problem itself. The solution lies in an education that will propel students into a higher economic class, where they will live better and therefore eat better.

But if Waters is applying the Wahington-money-fits-all-problems approach, Flanagan is hardly a Hayekian herself; she simply wants a different federal program with different classroom priorities to make good middle class taxpayers out of all those kids. And is there any evidence her kinds of government programs are working in inner city schools at a notably higher rate of success than gardening is?

At the same time I was reading this, I read a piece on minority Chicago schools by Heather MacDonald in City Journal, which is published by a conservative think tank; okay, I know many people checked out right there, but there’s some solid, if grim, reporting in the piece that will leave you better informed about how something like the Derrion Albert beating death happened. (There’s also, admittedly, quite a lot of use of it to bludgeon the record of the area’s most famous ex-community organizer.) The argument here is that Chicago social programs are very much focused on defeating social pathologies by raising the kids economically to the middle class with government spending. Their (decidedly conservative) argument is that this has it backwards— middle-class responsibility will be achieved not when it’s handed to those unprepared for it, but when they have it inside themselves and raise themselves to the middle class:

Now, perhaps if [school superintendant Ron] Huberman’s proposed youth “advocates” provided their charges with opportunities to learn self-discipline and perseverance, fired their imaginations with manly virtues, and spoke to them about honesty, courtesy, and right and wrong—if they functioned, in other words, like Scoutmasters—they might make some progress in reversing the South Side’s social breakdown. But the outfit that Huberman has picked to provide “advocacy” to the teens, at a reported cost of $5 million a year, couldn’t be more mired in the assiduously nonjudgmental ethic of contemporary social work.

Talking about Boy Scouts in the context of schools run by gangs may seem like a joke— but it’s no moreso than talking about gardening, surely. Gad! Does this mean Alice Waters is a closet conservative, using gardening to infiltrate her sneaky rightwing ideas (like honesty and perseverance) into the school system?

Well, no, not exactly. But it might mean that Waters’ idea of liberalism is a broader and more thoughtful thing than Flanagan’s big-government-by-experts version. The hippie left of the 60s is usually portrayed as impractical and druggy, but it also had powerful strains of libertarian self-reliance within it— certainly within Waters’ world, it meant back-to-the-land types who ate or starved based on their own willingness to work, and who became her suppliers by assiduously seeking to produce the best possible produce for her restaurant.

And that’s what Flanagan just doesn’t get— gardening isn’t menial labor to Waters, it’s the pursuit of excellence. Waters wants kids to learn the self-reliance and discipline that farming teaches— and if that’s conservative, well then so is my kids’ hippie school and so are Thoreau and Jefferson, and liberalism has just given up some very important home ground for bad reasons, it seems to me. Flanagan is ultimately on the side of tests and credentialism and knowledge being dispensed from on high; Waters is ultimately on the side of developing the individual so they can achieve, and will want to. And that’s why Waters is more right than Flanagan about the value of getting the kids out of the classroom for an hour a day and cultivating their own gardens.

My head was still swimming with fish from the new Sky Full of Bacon podcast (that was a direct link to it, by the way, that will skip you past the ten zillion pierogi pics to follow), from the frenzy in which I shot the last interview on Tuesday, finished editing Tuesday night, watched it the next morning and wasn’t happy, restructured it completely and rewrote and rerecorded the voiceover on Wednesday, and posted it Thursday morning. It was done, I needed to forget it and move on, I needed new adventures. In short, I needed the Pierogi Fest in Whiting, Indiana.

Chicagoans tend to have a pretty dire notion of northwest Indiana but, as I knew from a visit last summer, Whiting is a proud and tidy little town, full of cute little houses with perfect square lawns and flowerbeds and, during Pierogi Fest at least, flying the Slovakian flag. And, it seemed clear, a cheerful sense of the absurdity of a festival devoted to dumplings.

Knowing her to be the source on small town food events, I called Cathy2 beforehand. She warned me that during the Friday night parade and lawn mower drill team performance, Pierogi Fest could be packed beyond one’s tolerance for crowds; she felt it had become more of a tourist event than an organic local festival. Well, I couldn’t go Friday night anyway, so I aimed for what I hoped would be a midafternoon lull on Saturday.

Timing was pretty perfect, actually; the ice cream and root beer stands had long lines but the pierogi stands were fairly quiet.

The fest stretches through four or five long blocks of Whiting’s picturesque main street (119th), with probably 8 or 10 pierogi stands as well as a variety of other refreshments and assorted local vendors of the sort you see at any street fest, everything from tchotchke sellers to tarot readers to a National Guard recruiter, as well as a stage area devoted to folk dancing and music.

Clearly there were going to be more pierogi than I could take in on one trip. I needed a strategy, and so skipped the first couple of vendors in favor of a name I recognized:

Lynethe’s, on 119th just a few blocks east of here, is well known as one of the best spots for pierogi, especially since John Kass wrote about it a few years back. Ironically it’s actually run by a Latino who had worked for the previous Eastern European owner, but it remains a pillar of the Whiting pierogi scene and was doing some busy frying even during this lull time:

So I figured Lynethe’s would be a good choice for a control, especially since I’ve cooked them at home (and still have some in my freezer from last summer). I ordered a sauerkraut one and a potato with cheese:

Lynethe’s belongs to the fried-crisp school of pierogiology. The sauerkraut I liked a lot, the potato oozed way too much orange cheddar, like Cheez Whiz Pierogis, I wanted just a note of tart bryndza-type cheese like they have at Smak Tak. Still, a good baseline for what would follow.

Buscia’s is a non-restaurant vendor cooking up pierogi in an assortment of 50s-style electric pans. They are apparently there to represent Whiting’s transgender community:

Seriously, I was totally drawn in by the promise of bacon buns in a combo, so I ordered the combo. The pierogi were a little mushy and just so-so; hamburger forgettable, potato decidedly better:

The bacon bun could stand to learn a thing or two about being lighter and fluffier, it was pretty much artillery standard, but it had great bacony flavor and was one of the best things I tried.

I walked past other, more improbable food vendors…

But this bunch, from a bar called Coach’s Corner, lured me in with some quick-witted banter and infectious enthusiasm. They were serving “chevaps,” which is to say cevapcici, ground meat sausages freshly grilled, and despite hardly thinking that I needed the minimum order of five, I tried them.

“You take pictures of your food before you eat it?” one of them asked.

“Well, you don’t want to take pictures of it after you eat it,” I said.

These were great, and I loved the simple butter-cream cheese stuff that came on the side. I’m definitely going to have to go back and give Coach’s Corner, 6208 Kennedy Ave. in Hammond, a try.

I haven’t been able to track down Victor’s Grill, if it’s a standing restaurant, and it may just be another homemade spot, but it looked promising, so I stood in its line for a few minutes (business was starting to pick up as lunch was digested).

These were kind of heavy, wrapping-wise, but the fillings were pretty good.

I wandered some more past the stage area and reached the block with the beer garden in it. Although business had picked up a little at other stands by now, I wasn’t prepared for the line at Dan’s, which stretched down the street and around the picnic tables:

What accounted for this wild popularity? Did everyone know that Dan’s was the place, or was this one of those psychological things where a line attracts more line because, hey, if there’s a line, it must be good?

I heard someone ask these very questions of someone ahead of me and the answer came back, “This is the only place where they’re not frozen. They’re totally fresh.” Well… I’m not convinced that that was the reason, because I’m not convinced you can tell the difference, frankly. Still, it wasn’t like I was too hungry to spend 15 minutes in line, so I did.

It is an impressive operation, a dozen bins filled with a dozen flavors, certainly the widest choice here by a comfortable margin.

I tried cabbage, sauerkraut and mushroom, and cherry (which squirted hot cherry juice all over me as I bit into it). The wrappers were a little rubbery from the holding method, but the fillings were outstanding, it wasn’t hard to see why this place was popular. As I picked up my order, I heard someone say that the spinach were the best, so now I have a reason to go back next year.

I’m often disappointed by Chicago’s small street fests because it seems like the same vendors are there at each one dishing up the same pork skewers. Pierogi Fest, though it had some commercial catering ringers, clearly draws real local cooks and earns a lot of local support as a result. I loved it, the small town feel, the enthusiastic goofiness of pierogimania, the women who clearly should not have been wearing “Hey, Nice Pierogies!” T-shirts yet did so anyway, everything. It’s a great Chicago-area event and well worth checking out on a sunny Saturday afternoon, the perfect day for it.

The following is something I wrote for my kids’ school’s newsletter, outlining some interesting spots for daytrips in the greater Chicago area, together with a few food recommendations either personally experienced or at least gleaned from LTHForum. Several of the places are discussed further in this LTHForum thread. If anyone from the school (or anybody else) sends me more ideas, I’ll update it.

* * *

We are big fans of summer road trips, the kind you can do in a day, see something that may not objectively be worth the drive, but makes for a great day of helping your kids discover the world and see life out of Chicago. Here are some places we’ve enjoyed within an hour and a half or less from Chicago, along with restaurant recommendations (this is small town America, so it’s mostly diners and drive-ins; vegans, you’re on your own).

AURORA— Aurora Regional Fire Museum has historic firefighting trucks and other equipment in a 19th cent. firehouse. Lunch: El Pollo Giro, 991 N. Aurora at Rte. 25.

GARFIELD FARM—19th century farm museum near Elburn. Mostly Wednesdays and Sundays only; best time to visit would be 1840s Days, June 27-28. Lunch: Bien Trucha, 410 W. State, Geneva.

GLENVIEW—Wagner Farm, Cook County’s last working farm, is now a museum; my son Myles does 4H there.

KENOSHA, WI— Kenosha has quite a remarkable array of inexpensive or free museums largely unknown to Chicagoans near the lakefront, including a new Civil War museum dedicated to the service of the Great Lakes states, the Kenosha Public Museum (a small natural history museum), and a dinosaur museum. There’s also a lighthouse you can climb and streetcars to ride for a quarter. Breakfast or lunch: Frank’s Diner, 508 58th St., Coffee Pot, 4914 7th Ave. Lunch/picnic stuff: Tenuta’s Deli, 3203 52nd St.

LAKE COUNTY FAIR—Carnival rides, animal and crafts competitions and more; look for us in the 4-H sheep barn. July 28-Aug. 2, Grayslake. Lunch: corn dogs at Squire’s Dog Haus on fairgrounds.

LOCKPORT/LEMONT— The Illinois & Michigan Canal has historical sites and walking/biking trails all through this area; the best-preserved lock is near Channahon. Lunch: Vito & Nick’s Pizzeria/Bowling Alley, 1015 State St., Lemont.

OTTAWA— One of the largest artworks in the world is in Buffalo Rock State Park a little southwest of Chicago—who knew? Effigy Tumuli is a series of earthworks shaped like giant river fauna; fun to climb over and try to make out what the shape is. Ottawa is the nearest town; for lunch try Row House Cafe, 728 Columbus St.

RACINE, WI— Racine has a very nice small zoo on the lakefront, 2131 N. Main, and there are some interesting playground areas for small kids on the beaches nearby. There’s also the Frank Lloyd Wright buildings at S.C. Johnson, which have some public access. Lunch: Kewpee, 520 Wisconsin Ave. Then swing by Bendtsen’s, 3200 Washington Ave., to pick up some kringle.

ROCKFORD— Excellent children’s museum, the Discovery Center Museum, 711 N. Main St.; also a nice small dinosaur/natural history museum, the Burpee Museum, 737 N. Main, and a public waterpark. Lunch: Not much, there’s a local chain called Beefaroo, various locations around town.

SOUTH HOLLAND—The Forest Preserve District of Cook County has several nature centers with exhibits and walking trails; one of the nicest yet least-known is in a large reclaimed preserve on the southeast side. Lunch: Schoop’s, 695 Torrence Ave., Calumet City

UNION— The Illinois Railway Museum has one of the largest collections of real live trains in the world, many you can walk inside or even ride around their property. Lunch: there’s an on-site restaurant, or Allen’s Corner near Hampshire on Hwy 20 is a good old-style country diner.

VOLO— Tiny Volo has the Volo Auto Museum, but the coolest thing is a swamp—specifically, the huge Volo bog, which has a floating walkway through it as well as a nature center. Lunch: Sammie’s, 799 E Belvidere Rd, Grayslake.

WAUCONDA— There’s a Lake County historical museum whose main exhibit, oddly, is about a big postcard printer in Chicago; also some historical stuff of the Capone era, a tribute to Waukeganite Jack Benny, etc. Lunch: Frank’s Karma Cafe, 203 S. Main St.

You read a million things on a subject and then you finally read the one that explains it all. Michael Barone, veteran political analyst, explains why GM and its unions have become a marriage made in Hell:

Unionism as established by the Wagner Act is inherently adversarial. The union once certified as bargaining agent has a duty not only to negotiate wages and fringe benefits but also to negotiate work rules and to represent workers in constant disputes about work procedures.

The plight of the Detroit Three auto companies raises the question of why people ever thought this was a good idea. The answer, I think, is that unionism was seen as the necessary antidote to Taylorism. That’s not a familiar term today, but it was when the Wagner Act was passed in 1935. Frederick Winslow Taylor was a Philadelphia businessman who pioneered time and motion studies. As Robert Kanigal sets out in The One Best Way, his biography of Taylor, he believed that there was “one best way” to do every job. Industrial workers, he believed, should be required to do their job in this one best way, over and over again. He believed workers should be treated like dumb animals and should be allowed no initiative whatever, lest they perform with less than perfect efficiency.

Taylor’s work was regarded as gospel by many industrial managers in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s, a time when many factory workers were recent immigrants, often with a less than perfect command of English. Auto assembly lines were organized on Taylorite principles to squeeze the last bit of efficiency out of low-skill workers. And squeeze some more…

Interestingly, management often sought to deny that things were run this way at all— hence the video clip at the top of the page, from a 1936 industrial film called Master Hands, which seeks to show that GM workers (right at the moment of the violent strikes in the late 30s) were not interchangeable automatons but skilled artisans, like sculptors or bootmakers. (The conclusion naturally being that Michelangelo didn’t need a union.) (Note the additional irony that Master Hands, beautifully made corporate propaganda, shows so much influence of Soviet filmmaking.)

Barone draws the expected conclusion that the unions are what keeps the automakers from changing:

Japanese automakers… managed their plants not according to Taylorism but by giving their workers more autonomy and more responsibility—by treating them like sentient human beings and not like dumb animals as Frederick Taylor taught. The Detroit Three by all accounts I have seen were slow to learn from this—and were even slower to apply the lessons the Japanese taught—because of Wagnerism. Japanese management required cooperation between managers and workers. Wagnerism insisted that all interaction between managers and workers be conducted on an adversarial basis. The 5,000 pages of work rules mean that GM can’t manage the way Toyota does…

Taylorism is pretty much dead in our society; no automaker free to make a choice chooses it as a way to manage its workforce. But its antidote, Wagnerism, remains.

I’m not so sure this is true— that Taylorism is dead. Watch the Discovery Channel’s “How It’s Made” and you’ll see an awful lot of conveyor-belt, repetitive-motion production that sure doesn’t look like kaizen management in action. But let’s accept that cars are not made in quite such a robotic function (except for the parts made by actual robots).

Nevertheless, there is clearly at least one industry that still has Taylor’s fingerprints all over it—one which a high percentage of Americans will have had some experience with, mostly in their youth. Fast food. I worked at McDonald’s in high school and my freshman year of college (the sum total of my professional culinary experience, incidentally, in case anyone was wondering). And the whole secret of McDonald’s processes was that they were broken down into such simplified, repetitive processes that even a slackjawed, inattentive teenager could be instructed how to turn out perfectly average Quarter Pounders in about a half hour of training. And once learned, the processes were indelible— almost 30 years later, I could walk into a McD’s during lunch rush today and take over the Quarter Pounder grill without a hitch.

That this was something less than really learning to cook was a lesson driven home to me when I tried to get a summer job the next year at a Denny’s-type coffeeshop— and it was explained to me that by the time I was trained to be even a barely competent grillman, I’d be leaving to go back to school. Ironically, though I had to recognize the truth of what he said— I hadn’t learned to cook, I’d learned to cook Quarter Pounders— there was one part of McD’s menu where the desire to impose Taylorist processes had run into the customer’s expectations, and real cooking was required.

Breakfast. Sure, the Egg McMuffin might have been a pure McD’s automa-food invention— eggs cooked to unnatural circles, each yolk broken on purpose so that there will never be an issue of customers wanting it runny in the middle or not. But the pancakes are pretty much pancakes, like at any other place; the scrambled eggs are pretty much scrambled eggs, and not screwing them up means exercising a grillman’s judgement as to when things are done and how to arrange them on the styrofoam plate. We might have been Taylor-trained baboons in every other area of the menu, but at least in this one small corner of the menu, we were Master Hands.