Contact Me

Email mikegebert@gmail dot com.

About Michael Gebert

Michael Gebert, editor-publisher of the Chicago-based online food magazine Fooditor and author of The Fooditor 99, is widely recognized as one of the most knowledgeable and innovative journalists on food in Chicago.

Born in Kansas, he worked for many years in Chicago as an award-winning copywriter for many top brands and advertising agencies. The author of a book on film, he began writing about Chicago food online non-professionally in the early 2000s, first at Chowhound and then as one of the creators of the Chicago discussion site LTHForum. In 2008 he launched his nationally-acclaimed video podcast and blog, Sky Full of Bacon, and began writing for publications including the Chicago Reader, Time Out Chicago, Saveur, the Sun-Times, Where Chicago, Maxim, First We Feast and Air Canada’s in-flight magazine, among others. From 2011 until its closing in 2013 he was the Chicago editor for Grub Street, a daily food blog owned by New York magazine, and followed that by two years as a regular columnist for the Chicago Reader. In 2015. he launched his own site Fooditor, and in 2016 published The Fooditor 99: Where To Eat (And What To Eat There) in Chicago.

His video work has earned national acclaim for its in-depth and personal approach to the food scene, and to date he has been nominated three times for James Beard Foundation awards, winning in 2011 for the “Key Ingredient” series for the Reader, for which he’s produced over 100 episodes. He’s participated as a food expert, speaker or judge on PRI’s Marketplace, Chicago Public Radio, WGN Radio, the Hamburger Hop/Chicago Gourmet, the Printers Row Book Festival, the Good Food Festival, Cochon 555, Baconfest, the Greater Midwest Foodways Association, 2nd Story and many other local events.

He lives on the north side (but eats all over town) with his wife and two sons, who think it’s normal when the chef comes to your table during dinner and asks if you want to see the kitchen.

Hey, Do You Have a Shorter Bio We Could Use? Michael Gebert is the editor and publisher of the online Chicago food magazine Fooditor and a James Beard Award-winning food writer and video maker based in Chicago. He has been a contributor to the Chicago Reader, Time Out Chicago, Where Chicago, Serious Eats, Thrillist, Air Canada’s in-flight magazine and others, and was the editor of Grub Street Chicago.

Photo: Click for upscale image:

photo: David Hammond

Click for downscale image:

photo: Myles Gebert

Work Samples

Go here.

What Is Sky Full of Bacon?

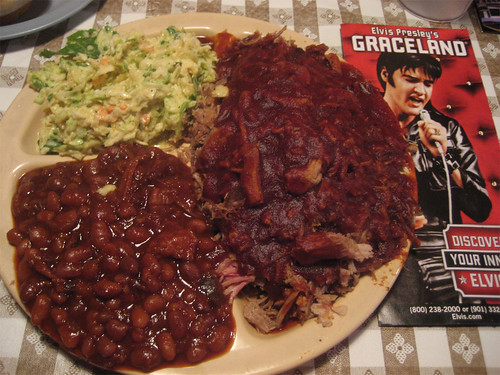

1. It’s Michael Gebert’s acclaimed series of video podcasts about food in Chicago and the midwest, which have been praised by the likes of the Chicago Tribune (“A great story… mouthwatering”), Michael Ruhlman (“great video”), Evan Kleiman (“Have you seen these videos? I think they’re fabulous”), Francis Lam (“Long but lovely”), Serious Eats (“always enlightening”), Saveur.com (“a blog that’s truly great”) and many more. Sky Full of Bacon-produced videos have been nominated three times for James Beard Foundation awards (in 2009 for these videos, together with Chicago Reader writer Mike Sula’s mulefoot pig stories in the multimedia category, in 2011 as half of the Chicago Reader’s Key Ingredient series, also in the multimedia category, which it won, and in 2012 for “A Barbecue History of Chicago.”

Chefs and food world figures who have participated in Sky Full of Bacon-produced videos include Grant Achatz (Alinea), Charlie Trotter, Nathan Myhrvold (Modernist Cuisine), Paul Kahan (Blackbird), Jean Joho (Everest), Doug Sohn (Hot Doug’s), Mike and Amy Mills (Blue Smoke/17th Street BBQ), Paul Virant (Vie), Stephanie Izard (The Girl & the Goat), Sean Brock (Husk), Fabio Viviani (Siena Tavern), Homaro Cantu (Moto), Dave Raymond (Sweet Baby Ray’s), Roberto Trevino (Budatai), Mike and Pat Sheerin (The Trenchermen), Takashi Yagihashi (Takashi), and Sarah Grueneberg (Spiaggia), as well as prosciutto makers Herb & Kathy Eckhouse (La Quercia), Zingerman’s owner Ari Weinzweig, cookbook author Nancie McDermott and Texas barbecue legends Bobby Mueller and Vencil Mares.

2. It’s also Michael Gebert’s blog about food in the Chicago area, which was named Best Local Food Blog by New City in 2009, nominated for a Time Out Chicago Eat Out Award in 2010 and a Saveur Best Food Blogs award in 2011, and featured as one of Saveur’s Sites We Love in 2011.

3. It’s a food video production company which makes low-glitz, high-interest online videos about the world of food for media outlets such as the Chicago Reader, Eater, Time Out Chicago, WBEZ (Chicago Public Radio)— and could do so for you, too. Check out our latest collaboration with the Chicago Reader, the James Beard Award-winning Key Ingredient series, with top Chicago chefs such as Grant Achatz, Stephanie Izard and “Hot Doug” Sohn.

4. And it’s an audio podcast about Chicago food and food media. Go here.

Posted in

Posted in