Next’s El Bulli menu is not Grant Achatz’s and Dave Beran’s take on the techniques pioneered by Ferran Adria’s restaurant, now passed into legend. There’s a restaurant that has offered that for years— called Alinea; it presented Achatz’s take on Adria, and Achatz’s take on Keller’s take on Adria, and in the process, it became simply Achatz’s, period. Next’s El Bulli menu is more like the test at the end of Michael Ruhlman’s The Soul of a Chef— we’ve seen how you cook your food, now show us how perfectly you can reproduce the original food it came from. Childhood’s food was the most like El Bulli’s food as food, but the El Bulli menu is most like the historical recreation of the Paris 1906 menu in spirit.

Or so it seems to me. Not that I had Paris 1906; not that I even had all of El Bulli. Roger Kamholz and I went to photograph opening night for Grub Street (he took the good pics, mine could only capture the blur of activity in this light… which is kind of cool in its own right, I think). And in the process, they wound up feeding us half the menu (nearly all the starters and all the desserts, not so much from the middle), while we stood— as out of the way as we could make ourselves, between the pastry station and the Mexican dishwashers— in the kitchen. Nothing, perhaps, speaks to how freely Grant Achatz deconstructs everything about dining as the fact that they deconstructed their own opening night for our benefit this way— an act of incredible generosity and graciousness given the insane demand for their product, with a surprise center of impishness, I think.

So this is a half review of Next El Bulli. But I had enough of it, at least, to overturn every expectation I walked in with. At an event a few weeks back, I was talking to Blackbird’s David Posey about the El Bulli documentary, which I saw on my flight back from Istanbul, and it turned out we had had the same reaction to the same scene— a moment late in the film where Adria and some of his chefs are talking to a fishmonger and buying some fish. And we both wanted to scream at the screen— “Just fry it! Don’t turn into a ball or a gel, it’s beautiful fish, just fry it!” Clearly I expected authentic El Bulli food to be the ultimate space food, the ultimate reduction of beautiful natural ingredients into the most extreme and unnatural globs and foams, with not even a hint left of the original physical integrity of the ingredient.

And at least one dish was like that to a T— the carrot foam (carrot air with coconut milk, El Bulli number 878 from 2003). Yet it wasn’t the desecration I feared, almost a consecration instead. It was carrot, freed of its physical form and made sheer carrot essence. The soul of a carrot, the spiritu sancto of a carrot, free at last to taste more like carrot than any carrot you’ve ever had.

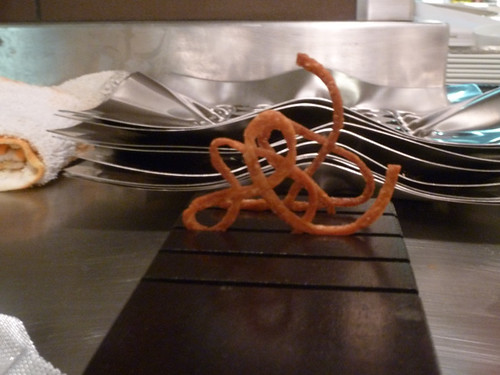

I said to Beran (as he plied me with food) that I was surprised how Spanish the meal was. For all that Adria had created technological marvels which had gone straight to that stateless international realm of global fine dining, for all that it was an American reproduction with American ingredients of a Spanish original (Maytag blue instead of gorgonzola for the gorgonzola balloon produced by liquid nitrogen, no. 1570/2009), it also took me back to Spain as firmly as the most authentic dishes at, say, Vera or Mercat a la Planxa do. I was expecting everything to be transmuted beyond nationality, but in fact many of the tastes were quite simple and spoke plainly of their origin— the briny roe at the center of a deep-fried ball (hot/cold trout roe tempura, no. 644/2000), the mellow greenness of the spherical olives (no. 1095/2008), the iberico sandwich in which pungent jamon wrapped around puffed bread (no, 859/2003). They spoke of their place (Catalunya 2000) in a way that I didn’t expect.

But they were also, I think, Spanish in another way. I am no great expert on the culture of Spain, but I’ve seen enough Goya paintings and Buñuel films and Gaudi buildings and whatnot to have a certain sense of Spain as distinct from France or Italy, say. To see it as a place where the medieval outlook toward the physical world— morbid and overheated— lasted far longer than elsewhere in Europe, so that when modernist movements arrived, they took off from a unique place of fascination with the grotesque. The Dutch Mondrian, reacting to the industrial world, painted neat little subway maps; the Spaniard Dali painted watches that decomposed like a carcass in the desert.

Okay, I’ve lost you when it comes to how that translates to dinner, I know. This paragraph won’t be quoted in anybody’s ad (“‘Morbid and overheated’— Michael Gebert, Skyfullofbacon.com”). But I think there’s an analogous Spanish sensibility at work here in working so hard to manipulate physical form, sometimes to escape mortal reality and touch the divine (that evanescent, immaculately conceived carrot foam) and other times to revel in the brusque contrasts of earthy, briny flavors like the coca of avocado pear, anchovies and green onion (no. 105/1991), a trumpet blast of in-your-face peasant worldliness. Buñuel, who found no joke more potent than to interrupt the most civilized of dinner parties with the shocking intrusion of mortality, would have been right at home this night.

Which, of course, couldn’t be further from Next Childhood, with its narrow emotional range tied to the palates and understanding of children, especially children of an idealized Ward-and-June midwest. Ironically, that night I went to Vera afterwards for a glass of Spanish sherry, needing to balance it with a taste from the adult world. By comparison Next El Bulli works a full range of emotional and sensations from the sacred to the profane, but I think it was the simplest and most transcendent ones that really captivated me, made me feel I had been somewhere that, for all El Bulli is imitated around the world, I had never been before. Phil Vettel dismissed the opening dish, the nitro caipirinha (no. 967/2004), as merely a nod to Adria’s pioneering work with liquid nitrogen, but a look at the date reveals there must be more to the dish than that; by 2004 liquid nitrogen was all over the world, pioneering it was long past. And in fact this starter (or is it an aperitif in solid form?) fairly screams that it’s no mere flash-frozen dessert, when the caiprinha ice is stirred together with fresh tarragon, as if to critique the use of liquid nitrogen with a reminder that fresh flavors will always trump frozen textures.

And then there’s the thing that was perhaps my favorite taste of the whole night— so simple it hardly even seems a dish at all, which perhaps accounts for why I have yet to see a single mention of it elsewhere. Yet for me it combined many the virtues of the menu as I experienced it— simplicity, daring, wit. It’s called mint pond (no. 1647/2009) and it is literally nothing more than a thin crust of ice sprinkled with peppermint and some other spice flavor I have since forgotten. You crack the ice (this could as well have been a Childhood dish) and suck the chips. Ice and spice, hardly food, yet it was entrancing and laugh-out-loud funny— not least knowing what the meal cost. Someone must be mad that they paid 1/28th of $365 for ice, but I went home smiling about the beauty and impertinence of this dish as much as I went home smiling about the crazy circumstances under which I’d eaten it, standing up in the kitchen of the hottest ticket in town.

If you like this post and would like to receive updates from this blog, please subscribe our feed.

If you like this post and would like to receive updates from this blog, please subscribe our feed.