Chef Jared Van Camp shows off the in-house pasta mill at his new restaurant Nellcôte. (5:04)

Next’s El Bulli menu is not Grant Achatz’s and Dave Beran’s take on the techniques pioneered by Ferran Adria’s restaurant, now passed into legend. There’s a restaurant that has offered that for years— called Alinea; it presented Achatz’s take on Adria, and Achatz’s take on Keller’s take on Adria, and in the process, it became simply Achatz’s, period. Next’s El Bulli menu is more like the test at the end of Michael Ruhlman’s The Soul of a Chef— we’ve seen how you cook your food, now show us how perfectly you can reproduce the original food it came from. Childhood’s food was the most like El Bulli’s food as food, but the El Bulli menu is most like the historical recreation of the Paris 1906 menu in spirit.

Or so it seems to me. Not that I had Paris 1906; not that I even had all of El Bulli. Roger Kamholz and I went to photograph opening night for Grub Street (he took the good pics, mine could only capture the blur of activity in this light… which is kind of cool in its own right, I think). And in the process, they wound up feeding us half the menu (nearly all the starters and all the desserts, not so much from the middle), while we stood— as out of the way as we could make ourselves, between the pastry station and the Mexican dishwashers— in the kitchen. Nothing, perhaps, speaks to how freely Grant Achatz deconstructs everything about dining as the fact that they deconstructed their own opening night for our benefit this way— an act of incredible generosity and graciousness given the insane demand for their product, with a surprise center of impishness, I think.

So this is a half review of Next El Bulli. But I had enough of it, at least, to overturn every expectation I walked in with. At an event a few weeks back, I was talking to Blackbird’s David Posey about the El Bulli documentary, which I saw on my flight back from Istanbul, and it turned out we had had the same reaction to the same scene— a moment late in the film where Adria and some of his chefs are talking to a fishmonger and buying some fish. And we both wanted to scream at the screen— “Just fry it! Don’t turn into a ball or a gel, it’s beautiful fish, just fry it!” Clearly I expected authentic El Bulli food to be the ultimate space food, the ultimate reduction of beautiful natural ingredients into the most extreme and unnatural globs and foams, with not even a hint left of the original physical integrity of the ingredient.

And at least one dish was like that to a T— the carrot foam (carrot air with coconut milk, El Bulli number 878 from 2003). Yet it wasn’t the desecration I feared, almost a consecration instead. It was carrot, freed of its physical form and made sheer carrot essence. The soul of a carrot, the spiritu sancto of a carrot, free at last to taste more like carrot than any carrot you’ve ever had.

I said to Beran (as he plied me with food) that I was surprised how Spanish the meal was. For all that Adria had created technological marvels which had gone straight to that stateless international realm of global fine dining, for all that it was an American reproduction with American ingredients of a Spanish original (Maytag blue instead of gorgonzola for the gorgonzola balloon produced by liquid nitrogen, no. 1570/2009), it also took me back to Spain as firmly as the most authentic dishes at, say, Vera or Mercat a la Planxa do. I was expecting everything to be transmuted beyond nationality, but in fact many of the tastes were quite simple and spoke plainly of their origin— the briny roe at the center of a deep-fried ball (hot/cold trout roe tempura, no. 644/2000), the mellow greenness of the spherical olives (no. 1095/2008), the iberico sandwich in which pungent jamon wrapped around puffed bread (no, 859/2003). They spoke of their place (Catalunya 2000) in a way that I didn’t expect.

But they were also, I think, Spanish in another way. I am no great expert on the culture of Spain, but I’ve seen enough Goya paintings and Buñuel films and Gaudi buildings and whatnot to have a certain sense of Spain as distinct from France or Italy, say. To see it as a place where the medieval outlook toward the physical world— morbid and overheated— lasted far longer than elsewhere in Europe, so that when modernist movements arrived, they took off from a unique place of fascination with the grotesque. The Dutch Mondrian, reacting to the industrial world, painted neat little subway maps; the Spaniard Dali painted watches that decomposed like a carcass in the desert.

Okay, I’ve lost you when it comes to how that translates to dinner, I know. This paragraph won’t be quoted in anybody’s ad (“‘Morbid and overheated’— Michael Gebert, Skyfullofbacon.com”). But I think there’s an analogous Spanish sensibility at work here in working so hard to manipulate physical form, sometimes to escape mortal reality and touch the divine (that evanescent, immaculately conceived carrot foam) and other times to revel in the brusque contrasts of earthy, briny flavors like the coca of avocado pear, anchovies and green onion (no. 105/1991), a trumpet blast of in-your-face peasant worldliness. Buñuel, who found no joke more potent than to interrupt the most civilized of dinner parties with the shocking intrusion of mortality, would have been right at home this night.

Which, of course, couldn’t be further from Next Childhood, with its narrow emotional range tied to the palates and understanding of children, especially children of an idealized Ward-and-June midwest. Ironically, that night I went to Vera afterwards for a glass of Spanish sherry, needing to balance it with a taste from the adult world. By comparison Next El Bulli works a full range of emotional and sensations from the sacred to the profane, but I think it was the simplest and most transcendent ones that really captivated me, made me feel I had been somewhere that, for all El Bulli is imitated around the world, I had never been before. Phil Vettel dismissed the opening dish, the nitro caipirinha (no. 967/2004), as merely a nod to Adria’s pioneering work with liquid nitrogen, but a look at the date reveals there must be more to the dish than that; by 2004 liquid nitrogen was all over the world, pioneering it was long past. And in fact this starter (or is it an aperitif in solid form?) fairly screams that it’s no mere flash-frozen dessert, when the caiprinha ice is stirred together with fresh tarragon, as if to critique the use of liquid nitrogen with a reminder that fresh flavors will always trump frozen textures.

And then there’s the thing that was perhaps my favorite taste of the whole night— so simple it hardly even seems a dish at all, which perhaps accounts for why I have yet to see a single mention of it elsewhere. Yet for me it combined many the virtues of the menu as I experienced it— simplicity, daring, wit. It’s called mint pond (no. 1647/2009) and it is literally nothing more than a thin crust of ice sprinkled with peppermint and some other spice flavor I have since forgotten. You crack the ice (this could as well have been a Childhood dish) and suck the chips. Ice and spice, hardly food, yet it was entrancing and laugh-out-loud funny— not least knowing what the meal cost. Someone must be mad that they paid 1/28th of $365 for ice, but I went home smiling about the beauty and impertinence of this dish as much as I went home smiling about the crazy circumstances under which I’d eaten it, standing up in the kitchen of the hottest ticket in town.

Note: if you’re here for the map showing you how to get to Ciya Sofrasi, scroll down till you see something that looks like… a map.

* * *

We arrived in the afternoon— Christmas Eve, though there was little to remind us of it— and the taxi took us to our hotel, a square three-flat on a steep hill facing an ancient city wall… as well as facing a tumbling wooden shack in front of which sat a brand new Toyota. Dark was coming quickly and when I went out to find somewhere for dinner, I took pictures of the turns I made so I could follow my pictures back to our hotel. With drizzle constricting my vision and twisty streets unmarked by street signs and only rarely lit by lamps, it didn’t feel like one of the major cities of the world— it felt like Tibet or something, one of the barely-reachable places, like the village ten thousand feet up where Indiana Jones finds his old flame Marion running a bar.

Even feeling lost and damp, though, I was taken in by the twisty streets and the low-level do-a-little-of-everything commerce, like the Lower East Side in the 20s or something. I quickly saw places I wanted to try to eat at— if I could find them again. Our first meal wound up being in a restaurant run by a Kurd, and it set the pattern for many— it took about ten seconds to have the proprietor or someone else talking English to us and telling us a fractured, semi-comprehensible story of his time in America doing something on behalf of some relative who had some business here, in amid parenting advice, famous Americans they knew of, and every other subject that could come up. Turks, we quickly learned, are as friendly and chatty as the Irish, and they seem to badly want you to like their country.

I hoped I could find this charcoal kebab place again.

The meal also set the pattern for meals— every meal, it seems, is grilled kebabs, rice, and bread. Pointing them all out would be like telling you where to get a Coke in America, so I’ll stick to the more interesting and anomalous ones from here— in particular, the restaurant that everyone seemed to know because it is the one Turkish restaurant that isn’t like all the others. It was a pleasant and welcoming evening… even as I held private doubts as to whether we could stand a week in such a remote and claustrophobic place.

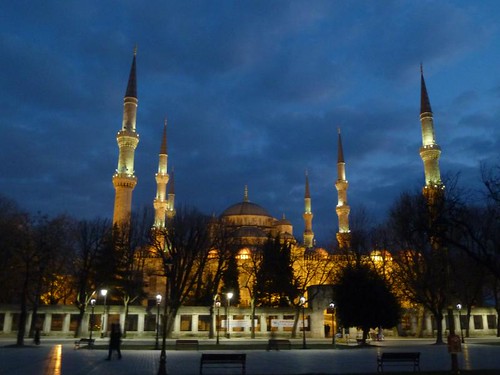

The next morning the rain was gone, the sun was shining… and Istanbul was beautiful, bright blue sky, dark blue sea, clean air (surprisingly little car traffic in this part, actually), a white city by the sea that could not have been more gorgeous, and my love was cemented. It was also, though we rarely thought of it, Christmas. We allowed ourselves to be seduced by a hotel at the south end of the Hippodrome and paid $15 a person for a breakfast buffet, not worth so much for what we ate (yogurt, dried figs, a croissant) but worth twice that for the view from the high point of Sultanhamet of the sea just a few blocks away— and the impeccably old world service by waiters who looked and acted like they were in a Poirot mystery on PBS.

Istanbul is the third largest city I’ve ever been to, after LA and New York (and much larger than Rome which preceded it), but it’s not a place people think of as a natural destination— to judge by the number of people who went “Hmm, why Istanbul?” when I told them about going to Istanbul and Turkey generally. Even if you’d think of going to there yourself, you might not think of it as an interesting destination for your kids. Yet it was all of that, and what’s more, one of those instantly enticing, vibrant and welcoming and youthful cities that always reminds me of Dr. Johnson’s line “If one is tired of London, one is tired of life.” That is what cities are— a grand bazaar of possibilities— and where I left Rome thinking “checked that one off,” I left Istanbul wondering how I’d get back.

The call to prayer, heard from a side door of Hagia Sophia.

Of course, part of it is that the tourist part of Istanbul hardly seems to belong to a city of that size; the area from Topkapi Palace to the Hippodrome is like Central Park in Manhattan, a rare open expanse in a city of crowds and twisty streets. By the numbers the “real” Istanbul is surely the rapidly growing, only moderately urban-planned areas outside the old city, the could-be-anywhere Blade Runner sprawl of glass skyscrapers and cell phone shops that you see stretching out forever as you go up the Bosphorus. The 2000 years of civilization before that are just baubles around its edges from the water. But hey, I visited that Turkish Blade Runner and thought it was pretty fascinating, too.

I’m still not crazy about Turkish desserts, especially anything with rose water.

The logical place to stay for a tourist is in the Sultanahmet neighborhood adjacent to the main tourist attractions (and convenient enough to most anything else). As it happened, technically we were in it, realistically we were below it, facing the exterior of the ancient city wall on its south side— and that would prove to be a good thing.

The hotels in the more touristed and populated area are probably fine, but the restaurants (in a strip right by Hagia Sophia and the Sultanahmet tram stop) tended to be the sort of mediocre, overpriced places that cater mainly to Australians and English looking to get drunk and rowdy; not surprisingly our worst meal and our most expensive one were one and the same, and in that area. (Islam’s prohibition on drink seems to be unknown to Turkey, which not only has bars but breweries and wineries.) Leaving that area and entering the claustrophobic twistiness was nearly always a better idea foodwise, and in time I came to love it too.

We spent Christmas day at Hagia Sophia— hey, I actually went to church on Christmas, for once— and then taking a two-hour Bosphorus ferry cruise, but at night we returned to our neighborhood and I tried to scout out some of the things I’d discovered walking around the night before. To my joy I found again the little shop where they were grilling kebabs over charcoal in the window— if one must have kebabs, these were the kebabs to have—

I found it again!

and then another where they made pizzas— or something pizza-like, though instead of round, the Turkish style seems to be a few inches across and literally two feet or more long. I returned clutching these prizes and this was our Christmas dinner.

The Spice Bazaar.

Sultanahmet has two famous bazaars, and what I’d heard before we went was that the Grand Bazaar was a vast tourist trap, while the smaller Spice Bazaar was more accessible and interesting. Yes and no. It’s absolutely worth it to go through the process once of being sold spices by a fast-talking salesman overwhelming you with bright colors and smells, and we came back with lots of vacuum-packed spices. That said, the Spice Bazaar is kind of, done one spice stand, you’ve done them all.

We went to the enormous, disorienting Grand Bazaar early in the morning when it was least crowded, which undoubtedly made it easier to like, but as full as it is of silly knickknacks, knockoff designer goods, Nike t-shirts and who knows what all (I went in in just a sweater, and was immediately descended upon by guys convinced I was there for a leather sportcoat), it’s also a place where you can find someone with a shop full of early 20th century tin-plated kitchen pots, surely as good a collection as any history museum in Turkey, and learn more than you ever dreamed about it in 10 minutes from the owner. Like Istanbul, the Grand Bazaar is life in all its clamoring variety, so vast and endless you suspect it must contain some sort of time-space distortion that allows a whole city to fit within a single building. I enjoyed roaming it and the markets extending around it for blocks immensely and would happily do more of it— early in the morning.

The markets continue all around both Bazaars for blocks.

Though honestly, you won’t have a bad meal by simply picking the nearest neighborhood kebab spot that doesn’t look totally discofied for tourists, the monotony of this dining could get to you after a while. The source for online intel on Istanbul eats is a blog called Istanbul Eats, and following their suggestions led us to the two best places by far that we ate at— which also happen to be the two places we ran across that had recently had major articles about them in New York-based media; funny how that works out, isn’t it.

The first was Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi, featured some months back in the New York Times. Doner kebab— the lamb stacked on a cone which is common enough in Chicago middle eastern restaurants, and basically the same as gyros— is everywhere, grilling in the usual doner machine. What’s not common at all— apparently unique in Istanbul in fact— is the pre-industrial version of the same thing, cag kebabi, in which the lamb is stacked by hand, the roll is roasted next to a fire and the pit master shaves off pieces for you, taking care to select meaty bits, fatty bits, charred bits and tender bits according to some algorithm only in his own head.

We ate there twice and did the same thing both times— we each ordered the standard two skewers, with a tomatoey red sauce, salad, a bowl of water buffalo soft cheese, and a big piece of floppy flat bread. Then, when we were done, we ordered two more pairs of skewers and shared them between us.

I used the word pit master advisedly because the care the owner, Ozcan Yildirim, takes makes him brother to any barbecue pit master, to anyone with a love for meat over fire, cooking anywhere in the world. When my kids think of Istanbul, I’m pretty sure the first picture that comes to mind is this:

Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi

Hocapasa Sok. 3/A, Sirkeci

212-520-3361

The other place worth calling out is not as immediately lovable as Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi, but offers more depth— which is why it got a lengthy piece in The New Yorker instead. Owner Musa Dagdaviren might best be described as the Rick Bayless of Turkey, though instead of finding traditions in a neighboring country, he finds them in the much less cosmopolitan east of Anatolia, bringing traditional home dishes to restaurants for the first time. He’s serious enough to have started a scholarly journal about traditional Turkish food, and when he finally publishes a cookbook, it will change the world’s perception of Turkish food (hopefully Phaidon will translate it as they have with other big national cookbooks). Traveling outside Istanbul among other Americans and Europeans later in the trip, we found that nearly everyone had heard of Ciya Sofrasi— because in a country of meat skewers, it seems to be the only restaurant serving vegetarian dishes. (His original restaurant is alleged to be vegetarian— which doesn’t stop lamb from turning up here and there. He also has a kebab place across the street.)

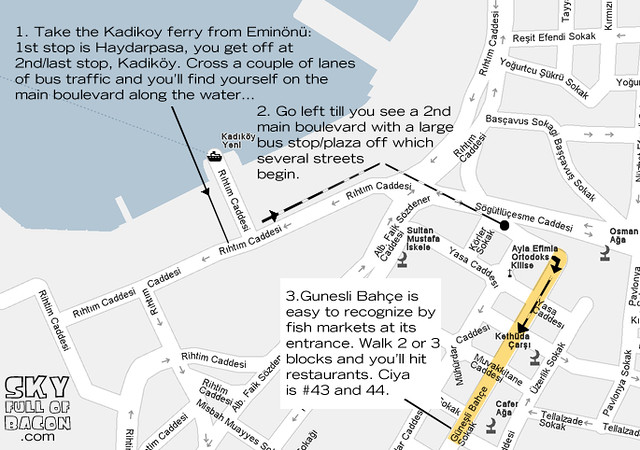

If you find this, you’re standing in front of Ciya Sofrasi.

Heard of Ciya Sofrasi, I should say, but found it hard to find. Ciya Sofrasi is on the Asian side, in a district called Kadiköy, near the Haydarpasa train station which is where, once your journey on the Orient Express terminated on the European side, you would arrive by ferry to continue on to… India? Siam? I don’t know.

Haydarpasa. You stay on till the next and final stop.

Anyway, Kadiköy is very much the modern Blade Runner place I was talking about, cell phones and skyscrapers and busy markets, and except for the ferry terminal none of it was on our map or indeed any map I could find. Even the best written directions I got took a couple of tries to match to reality, which is why I decided to put this map online to make it easier. You get off the ferry, cross the street to another cluster of bus stops…

look for the street that is full of fish markets, and start walking. After many fascinating markets…

You will hit a patch of restaurants, all of which will try to lure you in, American, Ingleesh? Very nice menu for toorists.

Keep walking and eventually you find…

There’s no menu you could likely read, but the food is all laid out behind glass. Just point and point and sit down and they’ll bring it to you. Don’t try to choose, don’t look for a certain dish as they change a lot, just point.

Salads; the thyme salad in front seems to be a particular favorite.

No idea what this was.

The stews all kind of look like this, but they’re different.

This leek-based one was my favorite.

Candied fruits for dessert.

Musa Dagdaviren is on the right. I don’t think he understood a word I said, but I hope he understood that it was genuine admiration.

In some ways they’re all very similar, and it’s not that there are lots of different flavors that jump at you, their satisfactions are those of things well stewed together. But here and there one thing will leap out, and they’re all as satisfying as soul food, and a break from kebabs for a night, for no more than about $1.20 on the ferry. Make your way back through the markets, consider whether you really need an Ataturk cover for your iPhone, and go back by the next ferry. You’ve been to Asia for dinner.

Ciya Sofrasi

Guneslibahce Sokak 43, Kadiköy, Istanbul

902163303190

http://ciya.com.tr/index_en.php

Whenever we saw this portrait of Ataturk, it prompted (very quiet) jokes about “the father of our country, Bela Lugosi.”

* * *

Cappadocia is the sort of place where they set up a wood-burning spiced wine stand next to a 600-year-old limestone city.

We spent a few days outside of Istanbul in Cappadocia (home of strange limestone formations and houses carved out of them, as seen in the original Star Wars), and Pammukale (home of other strange limestone formations that look like Antarctica, and a nice Roman amphitheater).

We went on tours arranged by this company, located right by the Sultanahmet tram stop, and while I’m generally firmly against tourbus travel, it was the only sensible choice here for this remote country and I recommend their services wholeheartedly. The tours were small (usually a 14-seat bus 2/3 full) with a guide who was engaged with the subject and happy to talk about other aspects of life in Turkey; while the home base took care of everything (including an itinerary change from the road) without a hitch. (Turkey, incidentally, has inexpensive regional airlines with brand new fleets, so we flew the long distances, very reasonably.) There is the usual shopping stop during the day, but of high quality (a pottery workshop, an onyx factory), and a lunch stop at some restaurant which was never spectacularly good but turning out pleasant enough homestyle food in an atmosphere of camel tapestries and swords on the wall that could have been anywhere from Morocco to Mongolia, seemingly. (The only thing I might say is that two days of limestone formations in Cappadocia might have been a bit much; if you want to cut it shorter, pick the one day in which you get to see the deeply creepy underground Christian city. To have come to that, literally a religious community burying itself alive in a hole in the ground, from the staggering worldly splendor of the Vatican a few days earlier is to get the most visceral feel possible for Christianity’s journey in the world over the millennia.)

The food in central Turkey— setting aside that it was truly winter at that elevation, where it had been fall in both Rome and Istanbul— was much more like things I’ve had in Georgian or Armenian restaurants than the meat-focused kebab cuisine of Istanbul, consisting mainly of simple stews and carrot-based salads. That said, I can tell you an infallible way to have a good meal in Cappadocia, even in the emptiest, most desperate for tourists time of the off season: look for a wood burning oven. If they have it, they’ll be making the stew inside a clay pot, which is a better show than a dish (they crack the tops off at the table; they’re sealed with dough):

but also they’ll be making pizzas, again, two foot pizzas. I’m not a huge fan of the Turkish basturma, the air dried pastrami-like meat which is very sharp tasting, but if there’s anything to be done with it, putting it on a pizza is it. And especially with kids, who were not inclined to be happy with a lot of vegetables or a plate of cold manti, no matter how much their father insists they’re just like ravioli (no they’re not, they’re cold and covered in yogurt), a Turkish basturma pizza is a godsend.

* * *

Dandurmas, with some kind of syrupy yet also stretchy topping.

Although I dissed Turkish desserts above, there was one we had just briefly on our last day (splitting a single cup between the four of us) that led to an amusing coincidence. It is maras dandurmas, a kind of ice cream made with orchid flour which makes it weirdly stretchy in the same kind of way that a lot of molecular gastronomy hydrocolloids do to food. After we got back I was shooting the new Key Ingredient, with Brandon Baltzley, and he mentioned (as you see in the film) dandurmas. But the film doesn’t show the exchange that followed right after:

ME: I just had that three days ago.

BALTZLEY (giving me an are-you-shitting-me look): Really? Where?

ME: Istanbul.

Sometimes life works out strangely neatly. So I’ve tried dandurmas twice in my life, on two different continents… in the same week.

Two new Key Ingredients since I last posted any— hey, I’ve been busy hanging out with my homies. First up, Bryce Caron, pastry chef of Blackbird and Avec, with Asian carp as his ingredient:

And then Brandon Baltzley with flour, this one’s almost as madcap and funny as the Michael Carlson one:

There’s a new Sky Full of Bacon podcast coming in the next few weeks… after its premiere at a special dinner put on by FamilyFarmed.org at Uncommon Ground on Thursday, February 23. Here’s the link for the dinner, which is 3 courses including wine at Uncommon Ground in Chicago.

Catching up here on past Key Ingredients; incidentally, please note that it’s going to every other week at the Reader, but keeps on keeping on past the point where any of us would have expected it to wear out its welcome, as Julia said in her recent 50th-edition piece. Anyway, the two over the New Year were, first up, John Anderes of Telegraph given the epistemological question of ash by Jason Hammel:

And then, Erling Wu-Bower of The Publican using gold leaf, which he totally disliked on aesthetic/moral grounds, making this one one of my favorites for the tension between chef and ingredient:

One thing to note, though: Michael Nagrant and I looked at our respective schedules and decided we just can’t pull off the week-long year-end roundup this year. Partly due to other obligations (we both have steady gigs) but also partly due to feeling like we’re saying it all elsewhere (we both have steady gigs). Maybe somebody else, someone who’s still on the outside and a rebel, needs to do it and give us the hell we gave others, now that we’re establishment figures. Or maybe we’ll do it next year. But it just isn’t going to happen this year. If you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, here’s Year 1 and Year 2.

Some years ago I went to Florence and Siena. The image of dining in Italy that Americans have is idyllic— every Olive Garden ad bloodsucks that image of the table of hearty food and warm family in our collective head— so it often surprises people when I say that I found it almost impossible to find anything good to eat on that trip. Well, for dinner; for lunch we would stop at the central market or the bakeries nearby, and that stuff was always cheap and fantastic. Here was the bounty of amazing-tasting simple stuff that is Italy’s birthright. But let them actually cook it into a dish… there was the pasta place so bad we waved other tourists away, like the damned warning the living that there was still time to save themselves, and there was the Florentine steak place we picked out of Michelin which forever defined Michelin for me (snobbish, insanely expensive, twenty years behind the times). Honestly, one of the best dinners we had in Florence was Chinese food. It was almost as good as the old school Cantonese in Wichita.

Now it is many years later, Chowhound and LTHForum and Sky Full of Bacon and Grub Street Chicago later, and I think I understand better how to avoid crap places and suss out promising ones, in any culture. First, of course, is just to go where someone you trust says you should go; more on that anon. Second is learn how to recognize the signs of crap for tourists— the Coca-Cola-branded signage promising menu turistico, the lavish gelato bar (Americans are drawn to vast arrays of sweets like bees to flowers), etc. I’m not going to say we scored 100%, there were a couple of meals where we wound up spending $50 to feed the four of us hospital cafeteria sandwiches, but I also had several scores where we picked a place, a humble bar or bakery, and spent a relative pittance to have fresh-tasting, beautiful homecooked food served up by a smiling Italian mama or gent straight out of a 50s movie. Like this place:

This was the bakery just around the corner from our friendly B&B near the Colosseum, facing the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, and I could find its address for you, but I don’t want to recommend it (unless you stay at the same B&B), I want you to be able to find yours near where you’re staying. A bustling little bakery, freshly made sheet pizza (pizza al taglio) with simple toppings like ham and mozzarella or potato and rosemary, desserts, a few tables crammed into a space right in front of a door, traffic in and out, stuff like this in the morning:

And it cost nothin’ and I felt like a million Euros for being able to recognize it and direct my family there just a couple of hours off the plane. Same thing when we went to the Vatican, we stopped on the way for a coffee and pastries before our time in the Sistine Chapel (allow me to highly recommend going at Christmas, not because they do all that much different then— it’s not really a place that needs extra religious-themed decoration— but the crowds were a fraction of what they’d be in the high season). The place we stopped was just a little cafe, nothing special:

Luckily I didn’t see the Coca-Cola sign till after. Anyway, coming back at lunchtime we had a recommendation for a nice, if expensive lunch, and we got to it and they were still setting tables and vacuuming, wouldn’t open till 1 or 1:30, so we walked half a block back to the cafe to have something to tide us over for a half hour or so. And we sat there, and guys like this:

were feeding an obviously local crowd with stuff like this:

And it all smelled really good and was dirt cheap and I thought, are we chumps for waiting to eat a $100 lunch for four when this stuff is being served up all around us? Yes, we were. So we stopped being chumps and just had them make up plates of enough food for six or eight, and it was maybe $35 (and half of that was Cokes), and we dug in, and were happy as could be.

Or when we went to this place (again, because a lunch choice wasn’t open yet, after seeing Bernini’s St. Theresa):

And while we were waiting the guy came by with the fresh mozzarella and the mama opened the box and jabbed toothpicks in a couple of them and handed them to us to try:

And on and on like that. One thing I learned along the way: nobody knows how to microwave like the Romans do. Because that’s how a lot of this food was heated up in these little cafes and bars; they don’t have room or time for a big oven, they just pop it in the microwave, yet it was never hardened and rubberized like food is when American restaurants microwave stuff. I suspect part of it is that our microwaves are simply too powerful, compared to theirs; we death-ray our food by comparison. For once the fact that everything in Europe is smaller and underpowered was an advantage. Whatever it is, they know how to use technology without destroying the tradition the food comes out of.

* * *

Now, one place I would unquestionably recommend, just as it was recommended to me— actually, two different parts of the business were recommended to me separately, and I didn’t realize they were the same place until we got there. It’s Roscioli, which you might call kind of the Zingerman’s of Rome— a group of businesses devoted to presenting the best artisanal foodstuffs, which may seem redundant in Rome, but in a city where that humble bar-ball of mozzarella on a toothpick was something special, Roscioli’s are a cut or two above even that. Jared Van Camp recommended the main store for its stunning collection of cured meats from all over the region, as well as the chorus line of prosciutto and jamon iberico legs poised above the salume:

Looking at their website, I saw that Roscioli also served dinner— as it turned out, kind of a popup dinner spread throughout the store. Dining among the olive oils and salume was an irresistible idea, and so we went:

It’s not, I think, that there’s some great chef here, but there’s a good chef making the same stuff you’d have elsewhere, but with ingredients sourced at Roscioli’s level of quality, like a gooey alien-egg of burrata topped with shaved white truffle (you pick the amount by the gram):

Or this platter of mostly housecured meats, including a fantastic testa and a speck-like ham:

Cacio e pepe, the most everyday Roman dish, elevated by the outstanding quality of the parmesan:

Which brings us, though, to a conundrum. Roman pizza, wherever we had it, was great just because the bread was so fresh and simple and delicious, whatever you put on it got a gold frame for its own flavors. But I didn’t feel that way about Roman pasta at all. The best pastas we had were at Roscioli because the best things went in the pasta. Other pastas we had were fine, satisfying enough, but without Roscioli’s sourcing, they were no better than things I’ve had in many places in Chicago, and the pasta itself was always serviceable, not one of those things that makes you go, aha, so that’s why pasta. This was the case at Luzzi, a frequently-recommended-in-guidebooks spot near our B&B, where the wood burning oven’s simple products infinitely outshone our homey (in the not entirely flattering way)* pastas:

I frankly feel there’s more devotion to making great pasta in or about to unveil itself in Chicago (Nellcote, Balena, etc.— at least that’s what their press releases promise) than we saw anywhere in Rome; if there’s someone in Rome obsessed with making the world’s greatest authentic preindustrial pasta, a Poilane of pasta, we didn’t eat his stuff.

Anyway, meanwhile Michael Morowitz had recommended a place called Antico Forno. The trouble was, that just means “old-style oven,” there are “Antico Fornos” all over Rome. What he meant was just up a side street from Roscioli:

This was Antico Forno Roscioli, a bustling bakery with lots of food to go (and almost nowhere to eat). There was sheet pizza:

and an amazing array of baked goods for the Christmas holiday just a couple of days away:

We bought it and sat on the steps of this chapel a block away, like the poor with their crusts of bread:

Except we had this, the greatest ham sandwich of my life, as I mentioned in my ten best list for last year:

Another recommendation from Morowitz was a tiny bakery in the Jewish quarter— more the Jewish block— which he said specialized in a kind of chocolate ricotta cake. Alas, after standing in line for twenty minutes, crowded into it like a phone booth, the ricotta cake was sold out (not sure why the Jewish bakery was as busy as all the others right before Christmas, but it was). I came away with slightly burnt biscotti:

And the irony of remembering that I had seen exactly the thing I’d come here for earlier that day… at Roscioli.

I bet they do a great job with it, too.

Another pizza place that was widely recommended to me, notably by Tony Mantuano who says it inspired the pizzas at his new Bar Toma, was Pizzarium, which I wrote about more fully at Grub Street. It’s just a walk-up stand in a fairly modern neighborhood on the outskirts (easy to get to, though, since it’s just up the street from the Cipro metro stop), but renowned for the excellence of the sourdough crust, which more than Bar Toma’s, reminded me of Great Lake’s (and has a similar overnight retarding period before it’s baked).

There were all kinds of toppings— I regret passing on one that had mandarin orange slices on it— but again, simplest was often the best; the tomato bread with burnt spots was magical. Pizzarium, like Rome generally, demonstrated to me anew that the secret to eating well in Italy is to spend as little as possible… in exactly the right places.

__________________

A few extra notes:

* Better in all departments (especially the warm Italian mama welcome) was I Clementini in the same neighborhood:

That said, one night when we were tired we did return to Luzzi and stuck to pizza, and were all happy.

Gelato is everywhere, but everyone seems to agree that one place, off the Trevi Fountain, is a standout, Il Gelato Di San Crispino:

This despite being a bit surly and having few places to sit. I’d agree— for the fruit gelati, especially the pear (praised in the NY Times) and some of the fig ones. Dairy ones seemed less outstanding to me— fine, but not unique.

Here’s my list of ten best things I tasted this year, most of which you can still go out and have, though considerable airfare may be involved. As I did last year, I disqualified all the Key Ingredient dishes because they’re just one-offs made under unusual circumstances; I also decided not to count the one-night-only “Modern Midwestern Cuisine” dinner planned by Steve Plotnicki and Bruce Sherman at North Pond, although it was good enough to qualify and certainly has me interested in visiting North Pond again after some years since my last visit,not to mention some of the other restaurants involved such as Niche (St. Louis) and June (Peoria). (You can read more about it at Grub Street Chicago.) Michael Nagrant and I will delve into the year in far more exhaustive detail at some point this month, though we both took vacations at the end of the year rather than knock heads in time for Jan. 1.

10. My strawberry-mint-basil jam— For a party this year I made a Dale Degroff cocktail combining these flavors with gin. I liked the combination so much I made it into jam with good things I bought at the Green City Market, or even grew myself. It’s really good, you’re just going to have to trust me. Or make it your own self next year.

9. Corn cake and greens, Yah’s Cuisine— The least likely spot on this list goes to a south side vegan soul food restaurant visited after shooting an interview with Peter Engler for my barbecue video. Before the visit, I’d have said the soul in soul food inevitably came from pork; Yah’s deep, heartfelt food proves me wrong. (Or proved; there’s some reason to think that Yah’s is closed, though no one has confirmed that.)

8. Ham sandwich et al., Roscioli, Rome— We ate a fantastic meal one night at this artisanal deli/foodshop with a pop-up restaurant on its premises, full of great handcrafted Italian tastes, and had great takeaway pizza from its neighboring bakery a day or two later, but maybe the champ of all was the greatest ham sandwich of my life— as good a vehicle as any fancier dish for demonstrating how something can be even more than the sum of terrifically well-chosen parts.

7. Short ribs & spaetzle, etc., Perennial Virant— So, yeah, I said what the ad says I said, sort of, if you read this post it’s more or less there. But it’s not number one on my list, did I mean it? Well, yeah. I mean, there were other restaurants I loved on first visit (Vera and Telegraph and Bar Toma and who knows what), and they may well end up on a ten best list once I’ve been to them a few times, maybe even ranked higher. But Perennial Virant seemed like a culmination for Paul Virant as I’ve followed him over the past few years, his food a little more casual than in Western Springs, newly in a BoKa Group high-energy city setting, yet nonetheless fully realized out of the gate and perfectly attuned to my tastes. Even so, as successful as PV’s PV is, it seems half-overlooked already— there are so many openings, novelty smacks you in the face almost daily, and Virant has been such a familiar figure that you don’t think of him as having not been here all along and thus something new in town. So stop to smell the short ribs and spaetzle— Paul Virant, once out in the suburboonies, is now right down the street from you, buying from the market and cooking it that night to bring out all its smoky porky fresh farm flavor. Doesn’t that deserve as much cheering and insane hype as anything that happened this year?

6. Sehzade Erzurum Cag Kebabi, Istanbul— Winner of this year’s Screw the Fancy Stuff, Just Give Me Meat Over Open Fire Award goes not to the latest barbecue joint I’ve discovered, as it usually does, but to Istanbul’s possibly unique old school cag kebap spot, located near the Sirkeci station where the Orient Express ended. The preindustrial ancestor of the ubiquitous doner kebap, cag kebap is handcut lamb stacked onto a giant metal skewer and roasted sideways over fire, then hand sliced and threaded onto skewers. More to come on this in an upcoming Turkey post, but suffice it to say that the owner is brother to any great BBQ pit master— picking out just the right mix of crispy and fatty bits and occasionally rounding out a skewer with burnt ends from the tray below.

5. Tarte flambee, Paris-Brest, Balsan— Will Balsan under chef Danny Grant be around next year to make anybody’s list? With the sale of the Elysian it’s an open question, and pastry chef Stephanie Prida has already moved on to L2O. So this choice reflects the ephemerality of the magic that comes together in high end restaurants, but the two visits I’ve made this year to Balsan all confirmed that— especially for a hotel— this is a great big city restaurant with high capabilities and the kind of cosmopolitan atmosphere that makes you feel cool for living here.

4. Pleasant House Bakery. If the video above doesn’t explain why I keep going back for that mushroom and kale pie, go here.

3. Dry chili fish filet, Chairman Mao’s Favorite Pork Belly, and others, Lao Hunan— I said somewhere that this was the best Chinese meal I’d had in some years, then had to think what that previous milestone would be— which, in fact, was probably Lao Sze Chuan. In any case, an overfamiliar cuisine (Chinese, in all its gloppy Americanized familiarity) came to new life at Tony Hu’s newest and so far best attempt to showcase a particular regional Chinese cuisine— and teach us how much more there is to Chinese food that what we know and take for granted.

2. Lots of skewers, Yakitori Totto, New York— “If there was a place like this in Chicago I’d become an alcoholic just to hang out there every night. Or a yakuza.” Well, maybe there is one now, given all our Japanese bincho grill openings. I haven’t found its equal yet, but I’m willing to give them time. And my liver.

1. Everything, The Butcher & Larder— As I said in the Reader’s best-of issue: “When Rob and Allie Levitt walked away from Mado to open an artisanal butcher shop and have regular lives as a family, it was hard to see how cold raw meat in a case could compensate for the loss of all the beautiful things at Mado. Which just goes to show how little we understood Rob’s vision, and how quickly he’d turn his butcher shop into one of this city’s most essential spots for food appreciation, education, and evangelism.”

No place in town has given food more respect and meaning in the last year, no place, not even Next for all its fertile creativity, has thought more about food and done more to convey that thinking to its customers and get them thinking too. And if these all seem extravagant claims to make about a place selling raw meat for other people to cook along with a couple of prepared sandwiches each day, well, I’m at work on a video to validate that claim, so give me a little time to make that case in full. Working at the most elemental level of cookery, with the most direct contact with farmers and animals, The Butcher & Larder is the food revolution people like Michael Pollan write about at the level of rubber meeting the road. And that people have gone so wild for it is one of the most encouraging things to happen on our local food scene in years. None of which, however, should be taken to suggest that their placement at the top of my list is because of anything other than food— than the ground beef and sausages I’ve bought there for hamburgers or pizzas, the roast beef or porchetta sandwiches I’ve eaten there; the top spot is more than sufficiently justified by the amount of deliciousness they brought into my life last year.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I don’t usually do worst of the year, but the greatest disparity between hype/acclaim and actual execution had to be Shake Shack in New York, whose rare-well burger (one side was one, the other the other), frozen Ore-Ida fries and lukewarm shake would get Danny Meyer run out of Wichita on a forklift. But then, Wichita is a serious burger town, unlike New York City, which is a trendy burger town.

Here are other things I enjoyed in the last quarter, most of which you could go have now; you can see previous quarters by clicking on “Best Things I’ve Eaten Lately” under Categories at right.

• Red snapper, bluefin sashimi at Arami, though didn’t like the cooked stuff nearly as much

• Chestnut and buttermilk doughnuts, Doughnut Vault

• Fish course, cider doughnuts, Madeira-maraschino cocktail, Next Childhood menu

• Chocolate frosted cake doughnuts, Zettmeier’s in Tinley Park

• Speculoos shake, Edzo’s

• Rabbit bolognese, octopus, Telegraph

• Pork belly, octopus, Vera

• Lentil (maybe) soup, Barwaqo Kebab

• Bob Andy pie, made by me

• Duck sugo, fish & chips, Owen & Engine

• Low country oysters, Chicago Food Film Festival

• Sunchoke-hazelnut soup, Acadia (preview)

• Walleyed pike, Cafe des Architectes

• Olives, burrada, espresso at Bar Toma

• Shoyu ramen, Takashi

• Tequila manhattan at Trenchermen preview

• Potato pieroshki, Bai

• Honey Butter Fried Chicken at Dose Market

• Blueberry-bergamot preserves by Marianne Sundquist/Mess Hall & Co.

• Strawberry marshmallow, 240sweet

• North Shore Distillery Aquavit, at Ikea Julbord dinner

• Omelet full of lentils at Lula Cafe

• Side of blue cheese coleslaw, Knockbox

• Assorted dishes at Ciya Sofrasi, Istanbul, post to come

• Assorted pizzas at Pizzarium, Rome, post to come

The 50th episode of Key Ingredient— that would be about 4 hours’ worth so far, if you were going to watch them back to back— is this week, starring Jason Hammel of Lula Cafe.

Julia Thiel, my partner in chef-torment, has a cool remembrance of our year of eating weird stuff in nice restaurants. As for me, it’s time to recount how the last ten were, as I do every ten episodes (click on Key Ingredient at right to see any of these):

• Luke Creagan/bamboo worms: Fried, they were just fine with cheese, French fries and mustard.

• Dirk Flanigan/sugarcane: Flanigan worked his butt off to experiment with this in so many directions; I wish I loved some of them more but they didn’t always pay off (like the pink powdery sawdust). The dish was fine in itself, it’s just that sugarcane didn’t contribute as much to it as one might have hoped.

• Kevin Hickey/Mountain Ash berries: the berries were fine, very well made upscale dish— but what blew me away was the squab, easily the best and most flavorful of that bird I’ve ever had.

• Beverly Kim/black cardamom: One of the few I’ve actually made at least part of— I made her black cardamom ice cream, which was very good.

• Edward Kim/turtle: A very pleasing pot pie… but turtle is just one of those ingredients that doesn’t have any character of its own, really.

• Kristine Subido/balut: I’m the only one who wasn’t grossed out too much by the fetal duck to eat this. I was actually more grossed out by the overwhelming egginess of it.

• Ariel Bagadiong/haggis: This was really tasty— the slight Asian touch on a funky comfort food dish was totally pleasing.

• Rodney Staton/calves’ liver: I can eat calves liver but I don’t love it, that’s for sure. This was an elegant approach, but still, liver comes through like a bell.

• Mike McGill/grass jelly: I didn’t get the bitter aftertaste from the grass jelly, so this was just a pleasant ravioli to me.

• Duncan Biddulph/cod milt: Although the cod jizz stunk up my fingers for two days, in the dish it was just a subtle brininess. I still find the idea of putting it on toast repulsive, though.

• Jason Hammel/gjetost: I thought this was pretty irresistible, actually— he was dead on about giving it some bitterness to cut the cheese (so to speak). I got the sense that being both cheesy and sweet, Jason thought it was a little white trash for Lula, though.

The debut of a new blog a few months back devoted to what cabbies eat reminded me to pay more attention to this subgenre, which is truly the cutting edge of the immigrant experience in Chicago, places least devoted to serving any clientele other than the most recent immigrant from the third world, and thus offering, in a very gritty way, as direct a reflection of other cuisines at home as you are likely to find. This is not a new observation, of course; there were 24-hour Pakistani joints on the 24-Hour-A-Thon nearly a decade ago, which was one of the key bonding events of the earliest Chowhound posters becoming ultimately LTHForum. (I didn’t go on it, but I read Monica Eng’s account in the Tribune avidly.) Here are three I’ve been to recently, all worth a stop for at least something.

The sort of undefined slice of west Edgewater and Rogers Park between Clark and Ravenswood is a definite cabbie haunt and, not coincidentally, probably the city’s main concentration of African food. Barwaqo Kabob is an East African spot on an obscure stretch of Ridge, hidden back by Ravenswood cemetery, and it will serve to introduce several of the giveaway signs of a cabbie hangout, including 1) TV tuned to popular native channels (which means an Indian one for South Asians, and Al-Jazeera for the middle east and Africa), 2) communal seating (no one thinks anything of sitting right down in the bubble of personal space Westerners tend to expect exists around them), and 3) a menu whose existence is basically theoretical; what you get is basically whatever you see cooking behind the cash register. Which means, in fact, that there were no kabobs that day at Barwaqo Kabob. What I got instead was a plate of chicken and rice:

This was kind of bland in a mildly spiced, slightly tomatoey way, and, frankly, the vegetables and the chicken had a kind of industrial cast to them, as if they came from a large bag at Costco. What saved this was some sort of dark, bitter sauce served on the side, sour with tamarind. I don’t know that it was supposed to go with the chicken, but I used it that way, and it made it far more interesting. What really saved my trip to Barwaqo was the free soup that came with it:

I don’t know what it was exactly— mashed lentils would be my best bet, but I’m open to other suggestions— but it was powerfully garlicky, and full of deep stewed flavor. It was great; it’s worth ordering randomly among the entrees, just to get this soup. Barwaqo definitely deserves more exploration (and there has been some in this LTHForum thread).

Barwaqo Kabob

6130 N Ravenswood

Chicago, IL 60660

When Kennyz said there had been a 24-hour Kyrgyzstani place called Bai Cafe in a storefront in my neighborhood for the past nine months, on a stretch I frequently walk by (or at least I though I did), I found it hard to believe him— but I eventually found the city inspection records and he’s right. My only extenuating circumstance is that apparently it only put up a sign in the last month or so, and even now could easily be mistaken for a place that’s going to open soon, and hasn’t moved much of anything into the space yet.

But David Hammond and I popped in there late one night when most other options were unavailable and had a meal that was plain and perhaps best described with the word “sturdy,” yet had one stellar component— besides the warmth of the welcome. There were two employees at work at 10 pm— one a Chinese-looking man, the other a round little Eastern European-looking woman patting out balls of something. (To be honest, I’m not sure which of them was more likely to be Kyrgyzstani, if either.) After we looked, a bit hopelessly, at the menu written in impenetrable Kyrgyzanglish (stuffed into a plastic holder which, bizarrely, had some copies of papers from the City stuffed into it, the Asian-looking guy waved us into the kitchen and showed us what was on the stove— a soup, a stew of chicken wings and corkscrew pasta, some fried ovoid balls about which the little round woman beamed and said “pieroshki— you like?”

We said we liked all of it and the guy, rather than try to calculate an actual price, said “I give you some of everything and two pieroshki.” We said one pieroshki was probably fine, and sat down to wait.

The soup (below) wasn’t bad. A simple beef broth, with handcut noodles in it, it was easy enough to like if not something that will stay with me as the Barwaqo soup did. The chicken wing pasta— well, it was like something you might eat at home. Not my home, the home of someone who doesn’t cook as well as me, and doesn’t know how much to season stuff. Nothing offensive about it, but very plain, and the only thing to dress it up with at the table was sriracha, which seemed really incongruous with something kind of goulashy like that.

But the pieroshki— they were fantastic. I expected a dense ball, sort of like a samosa minus the seasoning, but in fact they were as light and fluffy as a beignet. We ate our one, then kind of looked at each other— and decided maybe we’d better have that second one after all. Which we did.

Bai Cafe

3406 N Ashland Ave,

Chicago, IL.

(773) 687-8091

Tabaq is a Pakistani (probably) place near the beginning of Clybourn, in the no-man’s-land before you start reaching things like the Apple Store, and nearly as white and tidy as that establishment. As I walked in I got a serious stinkeye from an imam-looking guy in a floor-length garment, to which I responded with a look of bluff German-American heartiness, but the actual proprietor couldn’t have been more welcoming and was happy to put together a plate out of the things lined up as a sort of buffet behind the counter. They had chicken tikka, fried tilapia and another kind of fish, nihari, and a couple of vegetables; I tried to suggest vegetables, but wound up with two meats and a plate of lentils over white (not basmati) rice, along with some salad/garnish type vegetables and a small bowl of very thin coriander sauce.

The tikka was very good; the lentils were good, though the bland rice sucked flavor from them and I tried to eat them off the top of it; the fish had a nice spice but muddy flavor (catfish maybe). Unlike my other two cabbie meals, this one was of a cuisine which I actually have experience with, so I can say that it wasn’t the best of its kind I’ve had, but it was pretty decent, and I’d go back to check out more things, and especially to push to try some of the vegetable dishes which included some things I hadn’t seen before.

Tabaq Restaurant

1245 North Clybourn Avenue

Chicago, IL 60610-6655

(312) 944-1245

Posted in

Posted in