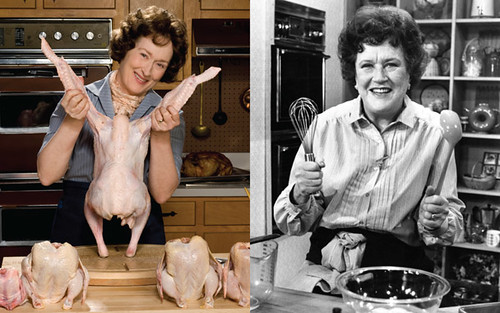

Permanently behind the times on new movies now, I watched Julie and Julia courtesy of a Starz preview a couple of nights ago. Streep was a hoot, a caricature of Child that nonetheless captured the woman bursting with life in a Muppet’s voice; as her husband, the normally sharp Stanley Tucci was so sweet and supportive you eventually wanted to smack him with a hammer (he also looks too Hollywood-fit for 1946); while Amy Adams and Guy Who Played Her Husband struggled to have more to their characters than the sloppily-dressed slacker couple in a cellular phone commercial. (I’m a blogger! Can you hear me now?) Still, this was better, and more likable, than I expected, even ever so slightly formally inventive for second-generation chick flick auteur Nora Ephron (whose parents wrote Desk Set for Tracy and Hepburn back in Julia Child’s day).

By giving us a lush 1950s story and a much more cramped and neurotic modern parallel, it’s basically a deconstruction of one chick flick subgenre, the career gal movie. Back in the day, a career gal movie was about a young woman who goes to New York, pursues a career and independence in some field open to women like magazine publishing and advertising, fends off some powerful but married wolf, and winds up happily ever after with some lesser hunk of 1950s actorly cheese. (The masterpiece of the genre, of course, is The Apartment. This is of course because it transcends the genre with a career that sucks, a wolf who isn’t fended off, and an ending that only barely manages to seem happy.)

But Ephron, aiming at a better educated female audience than the latest Matthew McConnaughy rom-com, switches the tables around. Both Julie and Julia are married as the movie begins; the real prize at the end is something a mere husband pales next to— a book contract. (I will assume that spoilers are by definition impossible with this movie.) So this is a romance about two women groping their way toward the greatest of all loves, of an author for her name on the cover of a book.

Except one of them is reading and cooking from the life of the other— so one is basically living in a movie which the other is watching. (They can never meet on the same temporal plane, of course, not least because Child lived long enough to sniff disdainfully at Powell’s blog— accurately, to judge by the banal excerpts we hear or read onscreen.) Julia and Paul Child live in a Paris where there’s room to park a motorboat of an American car, buy whole fish at the market in gloves and pearls, and throw parties in your vast apartment managed by a smiling, welcoming concierge. That they may have actually lived this life (except for the welcoming Parisian concierge, a detail I refuse to believe) doesn’t make it any less movie-like, and as fantasy Europes go, it’s as confected and irresistible as Mary Poppins’ London. There is some modest struggle for Julia in getting to her consummation with a publisher, but basically, the movie Julia Child goes through life like a parade float.

Where Julie has all the struggles of the modern caricature— a comically dilapidated Queens apartment, comically awful more-successful friends who use cell phones at the table, a comical encounter with live lobsters. (All credit to Amy Adams for whatever real feeling she can bring to this sitcom life.) The blog will be her way out, and frankly given Hollywood’s typical portrait of technology (all those high tech intelligence agencies still using c. 1988 green screen monitors that type one letter at a time) I feared how badly this movie would get blogging.

Not badly at all, actually. There’s an early scene which exists only to explain what blogging is in the simplest of terms to the older ladies in the audience, but once she’s online, the details seem pretty right. The problem I had was with the purpose the movie purports for the blog— which is to provide a new way in which someone whose pathway from editor of the Amherst literary journal to authorial fame had flamed out can mount a sideways assault on the publishing world.

And so while Julie’s rise is tallied in terms of her readers (“I got 55 comments today! From people I didn’t know!”), what’s dramatized are her encounters with the institutions of the New York publishing world— Child’s own editor Judith Jones (who jilts her), The New York Times (via Amanda Hesser, who comes to dinner playing herself), and finally, an orgasmic cascade of phone messages from big media brand names, Simon & Schuster and Food Network, this movie’s equivalent of the montage in an old musical in which we see the marquees of Alice Faye’s hit shows (“Lois Lovely in Damaged Woman… Lois Lovely in Hearts Over Montana… Lois Lovely in A Kiss For Princess Maria”).

Although plenty of people blog to get a book deal (or even, I’ve heard, to help attract freelance writing and videomaking gigs), by focusing all of Julie’s attention upward toward bigger fish in the New York media pond, her story ultimately misses all the other cultural shifts and implications of blogging in the course of leading her to the exact same publishing climax Julia Child (or Shirley Maclaine or Doris Day or whoever) would have enjoyed 50 years earlier. Some readers send her food items, but there’s no sense of bloggy interaction with her readership; she never learns better from them how to pull off a technique in Child’s book, she certainly never invites a learned reader to join in any of the meals she makes for her same batch of old, pre-internet real world friends. (The real Julie in fact did have events to which readers were invited.)

In short, there’s no sense that blogging might not be a way to crack the old media world so much as a way to get around it— to build your own audience free of media gatekeepers and editorial interference, a new form of communication entirely in which writers and readers interact. For the movie Powell, there’s nothing about blogging that wasn’t true about using your trust fund to publish a “little magazine” in Greenwich Village back in the day— it’s just a way to try out for the only show that matters, the big publishing show in midtown Manhattan. The irony is that Julia Child, who found herself in Paris and became famous in Boston, is less parochial in the 1950s than the woman who has the whole internet at her fingertips in the early 2000s— but never once thinks that if she hates her tiny apartment over a pizza parlor and her careerist friends, maybe she could try Portland, say, and do her blog just as well from there. Julie and Julia offers a curious picture of the evolving media landscape in which you can now publish yourself to the whole world— but you still have to do it from the 212 area code to be anybody, just like in Shirley Maclaine’s day.

Posted in

Posted in