Another blogger, one with a paying gig, mentioned to me the other day that she was going to have to start doing video for her job. There’s an idea for a blog post from me if ever I heard one! Lots of journalists are doing video these days and lots of them, sad to say, are doing video that doesn’t live up to the polish and professionalism of their writing. So I thought I’d put down a few pointers about how to make a basically competent, interesting, well-enough-made video, based on the… well, I don’t even want to think how many hours I’ve shot by now, but I’ve created enough finished product to have made Lawrence of Arabia already, with a Bowery Boys movie as a chaser.

Note that these are not trying to teach you how to make videos exactly like I do stylistically, or even in a similar format but with your own style. This is strictly about basic pointers, self-preservation for getting something you can work with to make something worth showing in the end— on a consumer-level camera with no crew or any other form of professional support. And though food is obviously my example, the advice here is pretty much applicable to any subject which an ink-stained reporter might find himself suddenly charged with making video about. I will start with the three things you have to, HAVE TO, pay critical attention to, and then follow up with a few secondary pointers.

THE THREE THINGS YOU HAVE TO GET OR DO TO MAKE A VIDEO:

1. Visuals

No shit, Cecil B., you say. But it’s not enough to simply point your camera wherever your eye looks and think you’ll have a movie in the end. Basically you need to focus on actively getting three forms of visuals:

• Master shots

• Insert shots

• Money shots

For instance, if you’re doing interviews, then the interviews are the thing you need to get first; they’re your master shot, the shot that provides the framework for everything else. And to get that, you need to point your camera at the person talking. And keep it there until you get the whole piece. They will say “Watch while I do this” and then what you need to do is IGNORE their direction to move the camera and look at what they’re doing and keep it on them while they talk. Or, you need to make it clear to them that they have to stop talking while you get the shot. But what they’re doing will be an insert shot into this master shot. So get your master shot, then take the time to get your inserts, one by one.

Inserts, as noted, are the closeups of plates or action or whatever that you put into your master shot. You need these not only because people will naturally want to see what is being talking about, but because you’ll use them in editing to hide cuts and pace the piece. Don’t expect to get these on the fly; even the cameramen on Top Chef often barely manage to grab these before food is gone, you’ll often see one that’s borderline out of focus or whatever, because it’s all they got in the hurry of competition. Plan to take some time at beginning or end to systematically capture these and have a full library of them when you’re done. You’ll always wish you had more.

And money shots… no, it’s not just about food porn. A money shot is the cool shot that everybody remembers afterwards, the one that tells the whole story, almost, in a single image. When you get one you know it. When the guy at Sun Wah inflated a duck with a gas station air hose, I knew I had a money shot. When the whitefish fishermen were pulling rope from the water against a painterly sky like sailors in Moby Dick, it was a money shot. This is just a matter of watching for gold out of the corner of your eye… while you do everything else.

Do you really need insert and money shots while doing a 90-second standup interview with somebody? Well, no, I guess not. But anything more elaborate than that will benefit from even a little careful thought and artistry applied to making sure you tell your story with images as well as with words. And that’s the difference between you telling the story and some bystander merely capturing it with their cell phone.

2. Sound

Another no shit item, you say, but it’s critically important. Especially if you’re working on one of those little Flip cameras or something. You’ll be shooting under noisy conditions, guaranteed, so you need to know what it takes to get decent, audible sound out of whatever camera you have. So at least wear an earpiece to make sure you’re getting something— a pro would wear complete headphones and only hear the captured audio, but I usually do it with half a set of earbuds in one ear— and do what you gotta do, such as getting up close and, again, capturing the whole thing, don’t move the camera away if it means the mic will be moving away too.

Somebody once sent me some Flip video they’d taken of a chef at work and asked if I could help clean up the sound. The problem was, they’d shot the work, not the chef talking, and as a result, aimed the mic at the food the whole time, not at the chef’s mouth. Understandably, they’d focused on the visuals, but the result was that the audio just wasn’t there; there’s nothing you can do about it at that point. Know what you’re getting while you’re getting it.

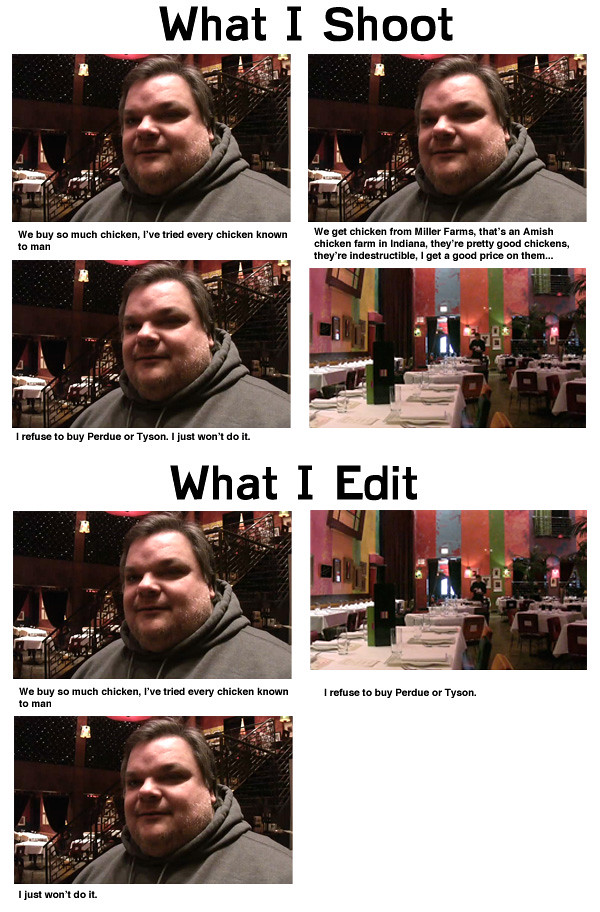

3. Edit, Edit, Edit!

It floors me when good journalists who’d sweat a print piece to perfection put a 5 minute unedited take up on the web. The falloff in viewership during the first minute must look like a black diamond ski run.

If someone’s making a blintz, we don’t need to see the whole thing from start to finish. Cut it down, cut to the interesting steps, cut down what they say to get to the heart of the matter, cut out the uhs and false starts and cover them with an insert shot. But cut, cut, cut, tighten, tighten, tighten, until you reach the point that there’s nowhere in your piece where you feel tempted to click to something else, and the whole thing surprises you that it ran seven minutes because it only felt like three or four. Editing is so easy in programs like iMovie, it takes no skill (I use Final Cut, which takes a little but is hardly rocket science). Your movie is made in editing the way your story only happens once you actually start typing; everything up to that point is just gathering raw material.

So those are the big three you can spend a lifetime getting better at. Here are some pointers based on experience, sometimes bitter, hardwon experience:

• Keep it steady, stupid… You can get by with some shakycam as you get your inserts, say, but if you’ve got a talking head, try to keep it as steady as possible. The best investment I ever made was $150 for this, I use it everywhere, but I also shoot handheld all the time… but try not to let it show too much. Steadiness in your master shot plus a more rough and ready style in your inserts cuts together very well and feels lively, yet won’t make anybody nauseous.

• …Especially if you’re using a Flip-style camera. The shotgun style of shooting handheld is natural for shooters and audiences. The idea of holding something shaped like a deck of cards is not; there’s still something alien to us as viewers about the way people shoot with that shape and weight, including a temptation to whip it around. Think of it as weighing ten pounds in your hand, and move it slowly and deliberately, like a barge. The video below was obviously shot with one, and it’s not a bad thing by any means, but I think you can just feel that it’s coming from something light and flimsy that jerks around too easily. Give it the heft of a big camera as you shoot.

• Vary your shots… especially if you’re using a Flip-style camera. There’s a temptation, especially with a small camera, to treat it like an extension of your eyes and shoot from your own perspective. Actually slightly below your eye level is often better because it makes your subjects a little heroic (unless it just makes them fat). But change viewpoint from time to time, including at different stages in your interview, just for visual relief. And get on top of the food and get it from whatever angle makes a great shot.

• Kill any background audio you can. Music will mess up your ability to cut, even if you don’t care about rights issues. It’s also distracting. If people are banging stuff, see if you can get them to take a break, or just go somewhere else. There’s no such thing as clean audio around food, and they’re not going to shut off a walk-in fridge for you, but do what you can.

• Clean your lens frequently. Food splatters, ’nuff said. I’ve discovered a glob on my lens just small enough to not show up on the LCD viewfinder more times than I care to remember. (Forget expensive lens cleaning stuff, get a lens cloth and a bottle of saline solution at the drugstore.)

• Script some interview questions ahead of time. You won’t remember everything while you’re worrying about everything else in a shoot. Also, you sound much better asking “How did you become interested in broccoli?” rather than “Okay, so I know— well, I read that piece that called you like the king of broccoli, not that you don’t do other, you know, like vegetables and stuff, and I was wondering— I mean, was there, you know…”

• Don’t talk over your interview subjects. Try to keep their speech as clean and whole as possible. Don’t have a conversation unless you really want your voice in there. Phrase a question, then let them talk and finish, completely. You’ll be glad you did when you’re trying to cut it.

• Don’t talk too much, period. If you have to explain everything with narration, it might as well be a print piece. I work hard at paring my setup down to as much haiku-like brevity as I can. It may not seem like it at first, but listen to the opening of my Chef/Farmer video, say, and see how quickly and briefly I set up a whole bunch of concepts about their relationship and the issues of scaling up artisanal farming. Then… I shut up for the whole of Mark Mendez’s part, and my voice only pops up a couple of times with David Cleverdon to pose questions. It’s not about me; I get my viewpoint in because I get final say on what they say.

• Don’t shoot too much. Steve Dolinsky said this and frankly, it’s one I don’t follow, because I’m not on deadline, and I can take two months to boil four hours of conversation into ten minutes. (I put long conversations on my iPod and listen to them while I cook or drive the kids to school, to find out where the best parts are without having to watch the same shot for four hours.) But if you have to finish your video in a day, exercise some editing control while shooting and get the key points down quickly from your subject so you have 20 minutes of raw footage to go through, not 6 hours (which is not at all unusual for me, but again, I’m not trying to make tonight’s 6 o’clock news).

• Charge your batteries and remember to pack them. Not that I ever made a bonehead rookie mistake like that, oh no.

Posted in

Posted in