Southern cooking [is] the one legitimate cuisine in this country… right there on the same level with French cuisine bourgeoisie and Italian cucina casereccia— the sacred traditions, the incredible variety of regional dishes, the prevalence of fresh local ingredients, the distinctive cooking techniques, everything. —James Villas

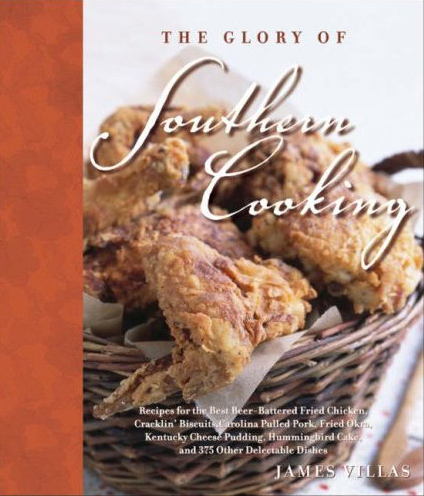

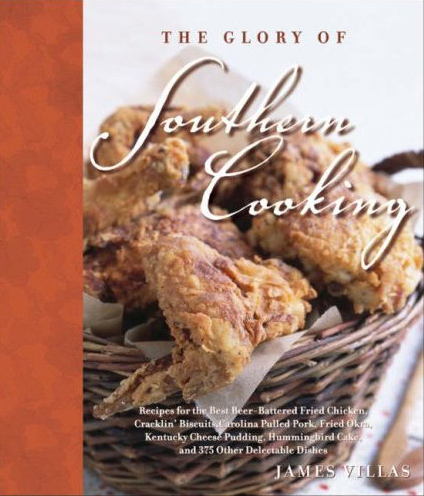

Not for James Villas the campy admiration for diner kitsch of the Sterns. When this food writer for Town & Country and compadre of Child, Beard and Fisher gazes into a waterfront shrimp shack, he sees a humble place as serious and timeless as a Tuscan guest-house. The Glory of Southern Cooking attempts to make an argument for Southern cuisine (from the Carolinas to Louisiana, anyway; Texas is exiled as its own thing, even as Cajun is embraced) being our great indigenous food tradition, meeting the most important criteria of European food greatness (as we’ve understood them since California in the 80s, anyway)—local, fresh and traditional.

Villas’ recipes only partly fulfill the traditional part—at least they include a fair amount of recently invented dishes from the likes of Frank Stitt, Paul Prudhomme and Paula Deen, and others Villas has doctored for modern tastes with a dash of heat or a splash of spirits. (The plainness of so many downhome recipes seems to demand tinkering from our more-flavors-the-better mentality, which those in search of authenticity must summon the will to resist.) Aiming to win a popular audience rather than shape an entire field of study, the book’s not as systematically thought-out or organized as, say, James Beard’s American Cookery, a truly magisterial survey. But neither is it downhome favorites for yuppies, and by focusing in particular on some of the older and nearly forgotten dishes Villas revives and documents here, especially from the least fashionable area of American cuisine, white society food of the 19th and early 20th century, one captures a fuller picture of a Southern cuisine that goes beyond the standard BBQ shack/soul food paradigm.

* * *

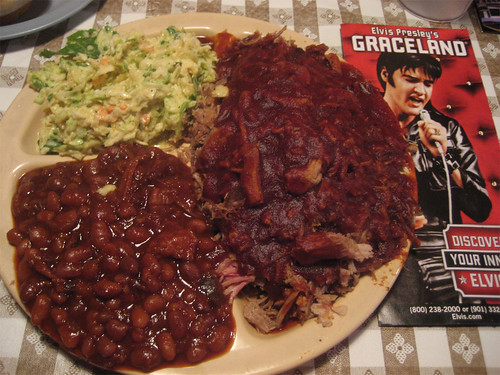

That at least was my goal when planning a meal built around some of the less obvious foods in Villas’ book. Having just taken a trip through Memphis and other nearby parts of the South, I didn’t have any intention of trying to outdo gastronomic temples such as the Les Troisgros of Nashville, Arnold’s, or the El Bulli of Lexington, TN, B.E. Scott’s at their own games. Here instead is what we had, beginning with the Cocktail Hour:

Pecan Cheese Biscuits, p. 19

These look like cookies but they are in fact savory short dough biscuits with parmesan and cayenne, bright and eye-opening in their spiciness, which Villas calls “the backbone of any respectable Southern cocktail party or tea.” He strongly urges good fresh pecans, which luckily I had just happened to spot at New Leaf in Rogers Park. Total made: about 45. Total left at end of evening: 0. Behind them in the bowl next to the burning-of-Atlanta-colored napkins are benne candies, basically a sort of sesame seed brickle, from Food For The Southern Soul. (Villas has a recipe for something similar, but I went for the $3.49 bag.)

Shrimp Deviled Eggs, p. 11

Deviled eggs are to Southern receptions what chowder is to Northern clambakes… the special compartmentalized plates… are as important as the eggs themselves. As one hostess uttered to me not long ago, ‘Anybody who serves deviled eggs on a plain ole white plate is just… tacky.’

Well, I’ll have to take his word on Northern clambakes. David Hammond and Carolyn Berg brought these (and have also been cooking from Villas at home), and while normally I am no great fan of deviled eggs, the addition of shrimp and capers (and having the requisite plate, of course) lifted these into another realm entirely– and made a convert.

Pimento Cheese Spread, p. 2

Cathy2 made this, not actually from the recipe in Villas’ book (the very first recipe, in fact, showing how central pimento cheese spread is to the South) but using authentic Duke’s mayo (well known for its aphrodisiac qualities). In fact, it’s one of the few Southern things to have made it into my Kansas childhood repertoire, where it probably only ranked second to bologna as a sandwich filling. Here Louisa Chu demonstrates the proper method of scooping it up with Ole Salty’s potato chips, which Cathy found in Rockford.

Fried dill pickles, p. 22

Since having my first fried dill pickle at The Violet Hour, where I thought they would be kind of a bar stunt food like fried Twinkies (but was pleasantly surprised), I’ve devoted a great deal of thought to this item, and tried them wherever I’ve seen them. Two things I’ve noticed: the coating tends to be formidable, often bolstered with corn meal, and the Jewish deli-style pickles used are often way too salty, producing a metallic clang against the crunchy greasiness of the coating.

Villas’ recipe, which claims to be that of the restaurant in Tunica, MS where they were supposedly invented, the Hollywood Cafe (a claim much disputed, of course), solves the first problem by going back to basics– this is a buttermilk, flour and egg batter, simplicity itself. For the second problem, I considered several possibilities, including a sweeter bread and butter style. Then I remembered a jar of pickles I had from Wienke’s Market in Door County, shoved to the back of my fridge. I’d found them a bit bland by themselves when I’d opened them a while back. But sliced into thinner subspears, battered and fried– they were perfect, just salty enough but not the teeth-on-aluminum foil jolt a deli pickle would have been.

People must have agreed with my assessment, because I wound up frying pickles for the better part of 45 minutes until residual moisture from the dipped pickles had weakened my batter beyond usability. Villas makes no mention of a dipping sauce, but I winged something off this Emeril recipe and it was perfect– or at least would have been if, at that point, I’d have had some Duke’s instead of ungentlemanly Yankee Hellman’s.

Ocracoke Clam Fritters, p. 36

There were a lot of oyster recipes in the book I was interested in trying, but somehow I felt that the middle of a party was not the time to be learning a new and somewhat dangerous skill, prying open a jagged rock-like crustacean with my First Virginia Volunteers saber. Instead I settled for this simple recipe using canned baby clams, from the Outer Banks of North Carolina, battered in a dill-flavored batter with homemade tartar sauce for dipping. I made the batter a little too salty, but they were a hit too, belying my inexperience as a bivalvist.

Sazeracs, p. 413

Originally made with a French brandy called Sazerac-du-Forge, the drink was probably created around 1850 at the Sazerac Coffee House in the French Quarter, but by the end of the century, the recipe had been changed to include not only a dash of local Peychaud’s bitters but also American rye whiskey and a little absinthe… when the city’s famous Roosevelt Hotel (today the Fairmont Hotel) bought the Sazerac House in 1949, rights to the cocktail recipe were included in the deal.

Many thanks to M’th’su for commandeering the business of making sazeracs, one of the oldest and still most harmoniously balanced American cocktails, even down to quickly making the simple syrup I’d forgotten to make during pre-party prep. In picking up supplies, he and I both were persuaded by the argument of a shelf display at Sam’s, which urged a house-branded rye made for exactly this purpose for them, they hinted, by the makers of a much more prestigious rye shelved directly above. I’m not sure if I’ve ever actually had a Sazerac before but I think I may have just found a new favorite, a little more unusual than the ubiquitous (if also harmonious and deeply venerable) Manhattan. (If nothing else, they fueled what has to be one of the world’s, or at least America’s, longest discussions of duck confit…)

* * *

Main Courses

Charleston Hobotee, p. 43

Innovative Charleston and Savannah chefs seem finally to be discovering perloo, awendaw, Huguenot torte, and any number of other distinctive dishes that once figured prominently in Carolina and Georgia Lowcountry cuisine. But, so far, not one seems to be even aware of this superlative curried meat custard that probably graced both breakfast and dinner tables during the plantation era… Served with glasses of semidry sherry as a starter to any seafood meal.

One thing I read or somebody told me that really struck me when I was in Barcelona was that much of Catalunya’s stubborn sense of separateness from Castilian Spain is rooted in the fact that for centuries, it was closer to Genoa or Naples than Madrid– in the way of traveling that mattered then, by ship.

Surely the same is true of what we now monolithically refer to as “the South”– until the railroad, at least, a port like Charleston would have had more frequent commerce with London than, say, central Kentucky. And London, of course, would have had commerce with all the world– not least India and other spice producing regions. Which explains how the powerful curry blast of a Charleston Hobotee comes to blow the doors off the stereotype of Southern food as comfily mild, white gravies over white starches.*

As you might expect from a 19th century dish, the recipe is purposefully vague in certain respects– you are free to start with a base of either beef, pork or veal, and all you are told about them is they should be “cooked.” I settled for pork shoulder in Alton Brown’s molasses brine, as being suitably Southern, and braised it with some onion and thyme until it fell apart. Mix the meat with curry, onion and some egg and milk-soaked bread, pour a custard over that and bake with a bay leaf:

One thing I have to say is: I just couldn’t buy the old American-style curry powder, one-dimensional McCormick with its taste of spicy ground phone books, which I grew to hate all those times my mom made curry dip for the artichokes she and my sisters loved and I loathed. Damn the authenticity, I had to use my good modern-tasting curry powder from Whole Foods. So my apologies if this actually tasted better than it was supposed to. (Though perhaps curries in 1850 were far better, even after a long sea voyage, than industrial ones in 1950.) I served it, per instructions, with an Amontillado (Alvear’s).

If there was a hit of the evening– well, along with Louisa’s buttermilk whipped cream in pro kitchen dispenser bottle– I think this was it, and indeed it would make a fine brunch dish. You can find the recipe by following this link and searching for either “hobotee” or page 43.

Maryland Terrapin Stew, p. 115

Perhaps no dish in Southern cookery was ever more relished or respected than the rich terrapin stews prepared in Baltimore’s ‘turtle-soup houses’ in the early nineteenth century—to such a degree that by the middle of the century, the stew had become the pride of the city’s Maryland Club and other elite social venues.

Where do you get a turtle these days? They went from being hugely popular to being hunted (fished? amphibianed?) nearly to extinction in the days of turtle soup a century and more ago. (Hence the mock turtle in Alice in Wonderland, with its calf’s head poking out of a tortoise shell.) I considered Chinatown, in fact Jazzfood and I poked around Chinatown Market for one one day, and no less a personage than Tony of Lao Sze Chuan gave me a few leads, but no luck. In the end I bought a turtle’s worth of meat partly butchered from Exotic Meats USA in San Antonio, filling out my minimum order with yak burger, antelope sausage and kangaroo brats. (I don’t know why my turtle said “Free Gift,” it certainly wasn’t.) The packet of recipes it came with includes “Roast Llama With Sweet Onion Sauce.” In case you’re wondering where to get that.

Cutting it down to the minced pieces spec’d revealed another reason for the decline of turtle soup: it’s very labor intensive. There are a couple of flaps of solid meat but most of it has to be sliced off thick vertebrae. I did this, slowly, and then tried making turtle stock out of the bones, an onion and a carrot. Two hours later… I had water that tasted like an onion and a carrot. With dinosaur bones in it.

Which is why a rich soup like this is nearly blood-clotting amounts of butter, chicken stock and sherry, with some onion, bits of hardboiled egg and the by now ubiquitous cayenne. Make the soup, and only then toss in the turtle meat– which frankly toughened as it went from ruby red to gray; I don’t know if I was supposed to cook it shorter or longer to be more tender, and I’m unlikely to find out from personal experience any time soon. Here was a perfect picture of men’s hotel dining circa the Chester Alan Arthur administration, the ideal soup to wash down six dozen oysters before the roast beef arrives on its platter, for a light dinner before going to see Lilly Langtry or Nellie Melba. In my case, it went with:

Grits, Ham and Turnip Greens Soufflé, p. 287

(I forgot to get a picture.)

Given the quantity of eggs used in this meal overall– at least 3 dozen– I didn’t really need to make another baked egg dish, but this was the one grits recipe that let me precook them and prep a dish I could just pop in the oven. It was damned good, though, I may make it again since I still have all the stuff. Stoneground grits (from the same place as the benne candies, no, they’re not whatever that trendy chef brand is), mixed with plenty of parmesan, cream and egg, with diced ham, blanched turnip greens and tabasco. Now this was comfy white starch.

Also served with this were:

Perfect Buttermilk Biscuits, p. 311

Accompanied by red pepper jelly (also from the benne candy link). People asked me if I made any of this stuff for practice beforehand, and the answer was mostly no, the success rate was probably a testament to how well-tested and foolproof these old recipes tended to be, compared to modern cookbooks full of things they just invented.

The one exception was biscuits– after ordering authentic Southern White Lily flour from Smuckers (who own or at least distribute two of the main Southern soft winter wheat flour brands, White Lily and Martha White), I pretty much made biscuits every night for a week, thinking of Evil Ronnie’s sage words on the subject of another Southern specialty. Over time, using up an entire 5lb. bag of fluffy soft flour, making well over a hundred biscuits, with some additional tips from Scott Peacock and Edna Lewis here, I arrived at my personal recipe– about 3/8 cup total fat, half my homecured bacon lard and half butter, to 2 cups flour and 1 cup buttermilk– and, just as importantly, learned how to just mix without smooshing them or kneading them. If they look good, well, they are good. (A little while later, at the dessert table, Seth Zurer said, “You’re a good cook but I think your real forte is that you’re a very good baker.” I will accept that, as a just compliment.)

You got pimento cheese spread on my biscuit.

* * *

Desserts

Lemon Buttermilk Chess Pie, p. 338, with Georgia Corn Custard Ice Cream, p. 379, and Chocolate Grits Ice Cream, from The Lee Bros. Southern Cookbook

There are only two ice creams in the book, somewhat surprisingly, so eager to get started a week before the party, I made a Georgia Corn Custard ice cream attributed to an unnamed faculty wife at the University of Georgia. You know, in high season, when corn is sweet and wonderful, it’s probably wonderful. In April, with corn out of a freezer case bag, not so much. Like I always tell Vital Info, you gotta eat local and in season to get the good stuff.

Desperate for a Hail Mary pass to save this part of the meal, I poked around other books and found this recipe for a very dark and rich chocolate ice cream with partly cooked grits for a little crunch, which the Lee Bros. (Charlestonian expats in New York) say was inspired by… a chocolate grits soufflé at Lutèce, the Manhattan four-star joint of the 70s and 80s. Of course. What could be more Southern? Oh well, at least it shows how Southern cuisine fits into the hoity-toity mainstream today.

Along with that I made a chess pie according to Villas’ recipe; until a few weeks ago the only ones I’d made, out of Camille Glenn’s Heritage of Southern Cooking (recently reprinted, get the old paperback cheap), had been plain flavored (that is to say, brown sugar and cream) and had formed a nice crust on top. Villas’ has buttermilk and lemon zest, which is fine, I think lemon zest comes awfully close to being almost any pie’s best friend, but it also had so many eggs it really formed a custard, not a crust, and also had some corn meal in the mix, which remains visible at the end. I cut the eggs down to get more of a thin and solid layer, and I like it just fine, but I may experiment with my own hybrid of the two recipes, I did like that almost cookie-like outer crust on the ones I used to make.

So that was what I made, although we also had coconut cake from Cathy from another Southern cookbook, which she may want to talk about:

and Louisa brought an all-edge brownie to serve with her buttermilk whipped cream:

and we even had a special surprise guest drop in unexpectedly straight from the airport whom we were all happy to see and offer a stiff drink and big plate of dessert to. So a great gathering of LTHers and, I think I can say, an interesting look throughout at a side of Southern cooking quite different in many ways from the stereotype, delicious as it undoubtedly is, of humble, stick-to-your-ribs soul (and country and western) food.

Posted in

Posted in