Since I’m going to an underground dinner tomorrow night, I had better finish up my own recent feast, previously chronicled (the country ham part) in this post.

I think I’m fascinated by Southern food because it’s the food heritage I never had. Southern food was on the periphery of midwestern eating when I grew up— Kansas may be more like Minnesota or Wyoming in many ways, but Oklahoma and Missouri are both strongly Southern-tinged, and so Southern influences often leaked over into Kansas diner food. It reminds me of childhood eating in little ways while having a rich and baroque folklore, exotic ingredients (crabs, cooters, okra, grits), colorful names and all the other things that desperately plain midwestern food lacked. When even something as common as biscuits and gravy seemed to summon up a whole Steinbeckian world of working-class joes and janes beyond my middle class growing-up, just imagine what the thought of crab shacks or hoe cakes portended.

There’s certainly loads of color to be had in a book like Charleston Receipts, the 1950 compilation of Charleston-area recipes which is said to be the oldest Junior League cookbook still in print. For starters, each chapter begins with a healthy dose of Negro dialect, and the recipes effortlessly cover the gamut from society balls and cotillions to downhome cooking of your catch in a cast-iron pot over a fire. There’s almost novelistic flavor even in things like the names of the contributors— one recipe is attributed to “Mrs. Serge Poutiatine,” a Charleston belle (nee Shirley Manning) who landed a Romanov prince. The recipes often show their origin in the era of canned vegetables, but it’s not hard to adapt them to their pre-Del Monte form.

So I took about half the recipes from Charleston Receipts, while most of the rest came from Edna Lewis’ and Scott Peacock’s The Gift of Southern Cooking, a more modern but generally authentic book not unlike the one I used at my earlier Southern party, James Villas’ The Glory of Southern Cooking. Here’s what we had, starting with appetizers:

• Punch. Green tea seemed to be the base for many punches in Charleston, and it was an interesting thing to try, the earthy flavor of tea standing out in what was otherwise a sweet and fruity punch.

• Cheese straws. Little twisted cookie or biscuit-like things with lots of cheddar in them, reputed to be inevitable at Southern functions (don’t have a funeral without them!) They taste exactly like Cheez-Its.

• Continuing that theme, one guest made pimiento cheese spread sandwiches:

• Spiced pickled shrimp. This was really tasty, you just basically make a mustard vinaigrette and pour it over some boiled shrimp the day before. I will make these again, and once we had them, I no longer regretted (as I had been doing) that I hadn’t done something with some more exotic sea creature.

• Another guest brought egg balls— I thought these needed an extra kick, dry mustard or something in the breading:

• Fried pickles made a return appearance:

There were other things, some smoked duck breast from a well-known supplier which another food writer brought by, a shrimp dip, some baked cornmeal mush things that Cathy Lambrecht had found in some book (they needed to be a vehicle for something else) and so on.

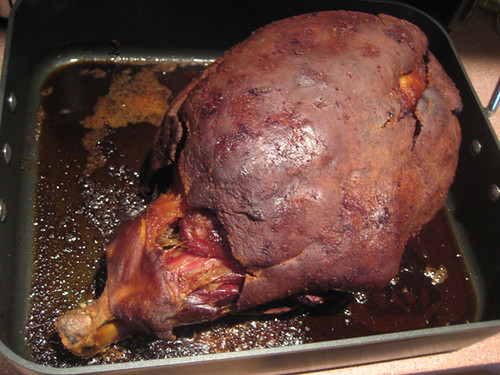

Following the appetizer, we had she-crab soup— actually we didn’t inquire into gender, just used the can straight from Costco— a simple soup (butter, sherry, butter and butter) that got raves even though I thought, so simple and basic, what’s there to rave about? Then, of course, the ham, previously discussed, served with turnip greens in a pot likker made from Paulina smoked butt and ham hocks.

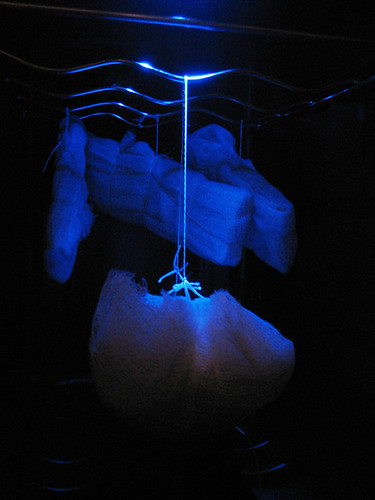

I believe, firmly, in many desserts and so we started with a Jell-O dessert called (wonderfully) a rum bumble, rum and a little rye mixed with cream and Jell-O. I actually made one batch of this and scrapped it, getting help from Cathy, fan of 50s cooking, as to how to mix Jell-O with cold things like cream without it turning grainy as the Jell-O hits the cold cream and instantly sets. Second batch (seen served here in Crate and Barrel tea lights) turned out perfectly.

Art and Chel Jackson (of podcast #7) brought molasses ice cream with a bacon cookie:

Finally, I was enticed by a recipe in the Lewis-Peacock book for what Miss Lewis regretfully acknowledged was known as Jefferson Davis custard. Two things set it apart: one was whipping egg whites separately from the yolks before baking it all as a custard, which made for a wonderfully light custard. The other was the fruit— can you name it?

The answer is: gooseberries. I’d bought them a year ago and frozen them, this was the perfect occasion to get them out and spend hours laboriously snipping off their hairy ends. The tart, tortillaesque gooseberries (no really; they have a discernable and often commented-upon tortilla-like note) and the sweet, delicate custard really went together beautifully.

The ham continues to give— I just made Navy bean soup with it— and the satisfaction of all these dishes as a collective journey deeper into Southern cooking was deep. If I start underground Southern dinners*, I’ll let you know.

* In a pig’s eye I’ll ever do that.

Posted in

Posted in