I can’t think of a hot trendy restaurant-of-the-minute opening that has produced more wildly divergent views than Chizakaya, the new izakaya-style quasi-Japanese place which I wrote about a couple of weeks ago. The official review-reviews are still pending, but first people on LTHForum went gaga for it, then I and some others went and were much more mixed in our appraisal, then another critic said he felt I was if anything too kind, but then Kevin Pang went and tweeted rapturously about much of it. With each of these appraisals I’ve questioned my own views— was I too harsh? Was I too easily gulled by good company and not wanting to be the one at the table who said “watta loada crap?” Or am I just being too cynical now and missing its fine and true virtues? What do I think I thought, really?

One of the questions for me, certainly, was how seriously to take the izakaya-ness of Chizakaya— and some of that, from me or somebody, has apparently gotten back to the folks at Chizakaya, who have tweeted on that subject a bit defensively:

My intention was not to take an izakaya from Japan, cut it out and place it in Chicago.

Just because you have had a hot dog in NYC doesn’t mean you can come to Chicago and say our hot dogs are different and wrong.

That goes with us here. Its not what you think when you think of a pub? This isn’t an authentic izakaya? WOW. Pubs vary around the world.

Fair enough. My conclusion really boiled down less to wishing that Chizakaya was an authentic izakaya, than to wishing there was one, somewhere in Chicago. The idea behind Chizakaya— an American pub with a Japanese slant— is reasonable enough. It could result in a “Japanese” place the way, say, Mado is an Italian restaurant— it’s not an Italian restaurant in the normal meaning of the phrase, but in other ways it’s the most Italian of restaurants, because everything it does is influenced by Italian ways of thinking about food.

But by that comparison Chizakaya’s record was decidedly more mixed (of course, so was Mado’s two months after it opened). Some things took that Japanese influence and really ran with it in novel ways— like the hamachi sashimi with bone marrow, which made every fussed-over bite of sushi at the late Kaze seem punk. Others could have been served at any of our new meat-centric joints, but were very good in themselves, like the beef cheek skewers; and others would have been more at home at Fun-On-A-Stick in the Towne Pointe Ridge Mall. (I feel basically ashamed about paying even $3 for the bits of chicken skin on a stick; it’s like paying a dollar to be allowed to lick a Popsicle wrapper. Ironically, grilled chicken skin is actually one of the most typical izakaya dishes on the menu; but there’s something especially preposterous about the tweezer-sized bits of skin threaded onto a skewer at Chizakaya.) Generally, the stronger the Japanese influence got, the more interesting dinner was, so I hope Chizakaya continues to move in that direction— not of becoming more authentic in a rigid sense, but of delving deeper into the culture as it riffs on the idea of a Japanese izakaya.

Which still leaves me wanting an authentic izakaya, somewhere, though.

Fortunately a few have existed all along, if not in the city proper, out in the northwestern suburbs where there’s a concentration of Japanese companies and, of course, the area’s largest Japanese market, Mitsuwa. One of them, in a strip mall in Mount Prospect, is called Sankyu, which (in the evening’s only note of hipster irony) appears to come from the way Japanese say the English phrase “thank you.” Unlike the chic Chizikaya, Sankyu has a slightly worn family restaurant feel (at least on a quiet Thursday), not unlike some other homey Japanese spots I like such as Sunshine Cafe or Renga-Tei. Sitting cross-legged at the traditional floor tables knocking back sake, we felt straight out of an Ozu movie, and that feeling was only enhanced by the two women who were our servers, kicking off their clogs each time they knelt down at our table to serve us, endearingly clumsy in their use of English… what businessman could resist a warm, increasingly boozy evening in their sweetly welcoming and forgiving presence?

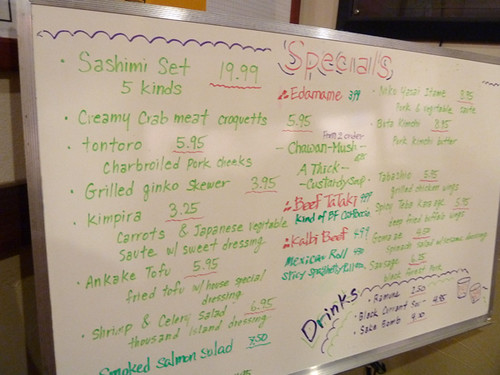

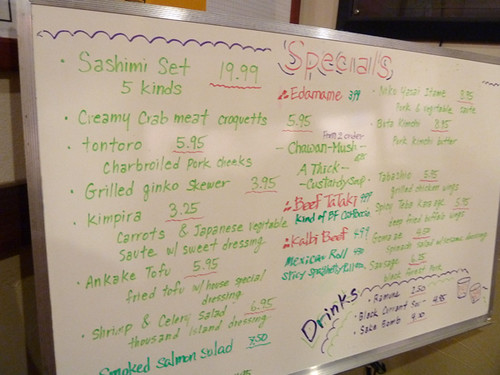

The only noteworthy mentions I’d found of Sankyu on LTHForum were from 2006, at which time the specials board was entirely in Japanese; now not only is it in English, but with internet-era user-friendliness, the paper copy in the menu actually marks some favorite dishes with a smiley icon. Many things were familiar enough from other Japanese restaurants to not seem specific to izakayas— agedashi tofu, goma-ae, etc.— but we managed to put together a group of dishes that seemed to fit the goes-with-a-lot-of-drinking, food on a stick profile. There were grilled whole smelt stuffed with their own roe, which you ate head to toe, and some little fried puffballs with octopus inside— Octodonut!— in a sticky puddle which screamed “supermarket steak sauce” as its main ingredient. When I ordered gingko skewers, our waitress raised an eyebrow and asked “You like gingko?” I said I had no idea, but for $3.95, how could I not order them, whatever they were?

I guess they were seeds, some sort of starchy globe, somewhere in flavor and texture between a lima bean and a bath bead.

Of course, there was meat. I ordered pork cheek, thinking it would be like the beef cheek at Chizakaya, though instead of tender braised meat it was flavorful, chewy grilled meat:

More tender meat came in the form of something described as pork cube, which turned out to be an unctuous hunk of pork braised in a sweet sauce, soft enough to pick apart with chopsticks (mostly).

As with the gingko, though, we were trying to go beyond the easily accessible things on the menu and order anything that seemed really unusual. One of the more surprising things on the menu— and probably a clue to Korean ownership, as is often the case with Japanese restaurants in Chicago— was something called “Pork Kimchi.” That in itself might not seem so odd— bits of sliced pork tossed in with kimchi. What was odd was the actual flavor of the kimchi, which wasn’t the usual red-hot sriracha-type sauce but a mysteriously funky, almost cheesy flavor. Cheesy as in, processed cheese food, a fake cheese taste. My dining companion and I both had to taste it and think about it for a moment, reach the point where we were sure we weren’t just imagining the flavor of, say, a Jeno’s Pizza Roll . But there it was, unmistakably and for real: kimchi with the taste of a boxed pizza-making kit from the 1960s. (NOTE: see explanation in comments. Evidently I need to eat more kimchi.)

Another strange taste experience came when we ordered deep-fried garlic. It came as a plate of little fried balls of irregular shape, a pile of them you could easily have believed was the testicles of some smaller animal. Our concern, of course, was that the deep-frying would hardly be enough to mellow the bite of raw garlic; so it was quite a surprise when they arrived so mellow that you hardly would have known they were garlic at all. Could deep-frying have taken the bite out of garlic that quickly? Even slow-roasted garlic seems to have more of a garlic sharpness left in it than these did. I wonder if they are some type of garlic known for, well, hardly tasting like garlic at all.

I suppose a comparison like this will inevitably lead to the question, so which is better, Hipsterkaya in the city, or Realzakaya in the burbs? The reality is, they’re too different to logically pair off, and who really needs to make an either-or choice, anyway? You know whether you want an urban hip meal in a new place, or a homey slice of authenticity on an otherwise bland suburban strip. Chizakaya’s chef comes from L2O and there’s obviously greater care and skill in the composition and execution of its dishes— sometimes to the point of preciousness, but certainly of a consistently haute-chichi level. Where Sankyu comes off about at the executional level of a good diner, as well as the portion sizes (and Chizakaya could have used a big hearty plate like, say, the pork kimchi, to avoid sending us out not-quite-full). Atmosphere is quite different and depends on what you want on a given night; price— well, three of us were not quite satiated for about $55 each at Chizakaya, and two of us were plenty full for $45 each at Sankyu.

The real difference for me came with one dish toward the end. In my writeup I described my vague disappointment that Chizakaya, good as it was here and there, hadn’t expanded my mind:

I had something else in my head, a place where deep-fried lotus root or pickled plums or such unexpected, alien-looking things would challenge me during my meal. And I’m still kind of eager to go eat at that place.

One of the last things we ordered probably should have been one of the first; it was the kind of palate cleanser-slash-eye-opener that would have set the stage for the meal. It was some kind of Japanese yam, cut into toothpicks— starchy, crunchy, like jicama. There was a sauce at the bottom of the bowl that looked like soy sauce but was brinier, almost tart, bracing [NOTE: see comments; it’s ponzu]; there was a quail egg, there was nori, there was some wasabi. And when you grabbed a bunch of the toothpicks with your chopsticks, it came up with a kind of alien-sliminess, leaving curving trails of slimy goo that stretched from the bowl, longer and longer until your mouth finally broke them and they sprang back. Hardly an appetizing thing to look at— and yet when you popped it in your mouth, the crunch, the briny sauce, the creaminess of the egg, the burn of the wasabi all combined to startle and then to amaze, to adjust your preconceptions about what food is. This was nothing like anything we eat in the west, it would surely turn off most people in five different ways, and yet my dining companion and I were both entranced by it, by its utter differentness and yet by its obvious success as a well-thought-out combination with, no doubt, centuries behind it.

Here was what I had come to the izakaya for: a meal of comfort food that, along the way, just happened to expand my universe and blow my mind.

Sankyu

1176 South Elmhurst Road

Mt. Prospect, IL 60056

(847) 228-5539

* * *

Sankyu having been the last meal of the quarter, it’s time for another list of the best things I ate in the last three months, which will then go into the semi-finals for my ten best list at the end of the year (previous quarterly lists here and here):

• Headcheese with chow-chow, Big Jones

• Tri-tip at Lillie’s Q preview event (photo above)

• Old Town Social’s cheese dog, MK’s snow cone, Green City Market BBQ

• Adam Seger’s Hum cocktail with lavender-jasmine tea, Reader party

• Pho at Pho 888

• Tete de Cochon, Longman & Eagle

• Doro Wat, Queen Makeda, Washington, D.C.

• Sliced pork and hush puppies, A&M Grill, Mebane NC

• This corn soup made with farmer’s market corn by me, about 10 times this summer

• Blueberry mint sorbet, Black Dog Gelato

• Beef shawerma sandwich, Taza Bakery (3100 W. Devon)

• Beef cheek skewer and hamachi with bone marrow, Chizakaya

• Three Little Pigs sandwich at Silver Palm, of which I tweeted: “Always looked like stupid excess. Actually very well made excess.”

• Peach blush (raspberry) jam made by Cathy Lambrecht and myself

• Pork skewers with fish sauce-palm sugar marinade winged by me when I couldn’t find all the ingredients in David Thompson’s recipe

• Panzerotti, pane panella, and tiramisu at Taste of Melrose (watch the video already!)

• That Japanese yam dish at Sankyu (see post above)

Posted in

Posted in