Continued from here.

Carr Valley Cheese, LaValle

Carr Valley is apparently actually larger than Roth-Käse or any of the others we visited, but scattered across several plants, so it has the feel of a smaller cheesemaker— at least when you visit its original building, built over the decades around a core that dates back to the early 1900s. Unfortunately, Sid Cook, its master cheesemaker, was out of town and only made an appearance in a video dating back to 1996. But we had a nice tasting of everything from cheese curds to some award-winning washed rind cheeses; I particularly liked the cow-sheep-milk blend Benedictine, a triple cream called Creama Kasa and another called Casa Bolo Mellage.

We did learn one amusing factoid about cheese at Carr Valley: you know why the traditional colors for the wax casing on cheddar are clear or white for mild new cheddar, red for a more aged cheese, and black for sharp, very aged cheddar? Because if they sat around without selling for long enough, red will cover a white wax coating, and black will cover a red one….

Cedar Grove Cheese, Plain

Cheesemaking was already finished for the morning by the time we made it to Cedar Grove in the town of Plain (a bit redundant as a name for a place in the midwest, it seems to me). And hey, we’d seen cheesemaking already anyway, so owner-cheesemaker Bob Wills took us to see his other pride and joy: an elaborate water purification system which runs the waste water from the cheesemaking process (rich in nutrients, since it started as milk) through a series of tanks where natural processes purify it to the point where it can safely go into the drains. Interestingly, he says not only does it cut the costs of dealing with water on its way out the plant… it seems to have made everyone in his plant think harder about water and use it more carefully and less wastefully, cutting his water bills on the way in, too. And in the summertime, they come out here and snack on the tomatoes and grapes.

Wills is a strong advocate for cooperation between cheesemakers, and often allows other cheesemakers to use his facilities to make cheese and to experiment with new recipes, treating his plant as a kind of entrepreneurial incubator. (He contrasted the Wisconsin cheesemaking attitude with what he saw on a consulting trip to Honduras, where each family cheese plant was protected by armed guards.) He made it clear that letting Willi Lehner, say, work in his facility and observing him at work was as much a benefit for him as it was for Lehner.

We tasted some cheese at his counter— he just grabbed it from the fridge and started cutting it up— but to be honest, by this point I can’t remember what we had, other than a water buffalo mozzarella which he had just made for the first time. (The farm, the only water buffalo herd in Wisconsin, is right across the street.) The texture was too hard, but he admitted he’s working without actually having been to Italy to try authentic examples of the cheese, so keep an eye on this one, it will no doubt get better.

Otter Creek Farm, Avoca

I was especially excited to visit Otter Creek, since I’ve been buying their cheese at the Logan Square Farmer’s Market for some time (and wrote about it here). I didn’t know the half of it. The owner of Otter Creek, Gary Zimmer, is a tireless character preaching his style of farming, which to the extent that I could take it all in a rush of enthusiasm, seems to be organic, rotational farming carried out very intensively to ensure the presence in the soil of all the minerals necessary for health and growth… and involving moving the cattle around a lot so they’re eating the right nutrients at the right time of day and year.

The knock on organic farming is that it doesn’t yield enough to feed the whole world— a comment usually delivered by agribusiness types in a way that insinuates that organic proponents want to cause mass starvation. Yet Zimmer claims that he gets yields from his intensive organic farming that significantly improve on conventional agriculture; and seeing the operation, I’m inclined to believe it, it’s the very opposite of lackadaisical hippie farming. (I was under the impression that the farm was biodynamic, and asked about that— and got a quick response about how waiting for the perfect moon to plant under is no way to get the best yields.)

Zimmer’s manager in much of this is his son-in-law, Bartlett Durand, who also has a shop selling local foods nearby, and he treated us to a vertical tasting of their seasonal cheeses, produced from the milk at different times of year, in a tasting room consisting of a Packers blanket thrown in the back of his hatchback. This was the first time I’d tasted more than one side by side and you could definitely taste its evolution— from more floral in spring to more dense-tasting and sharp in fall. We also tasted their spring cheddar studded with ramps, which has a wonderful wild flavor to it quite different from the usual flavored cheese made with supermarket vegetables in it. One especially interesting thing we learned from him: happy cows don’t moo, mooing is basically grumbling. By that measure, Otter Creek is an unusually quiet and contented farm.

This Otter Creek Farm property (there are several) belonged to one of the architects from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesen. Could you guess from this barn?

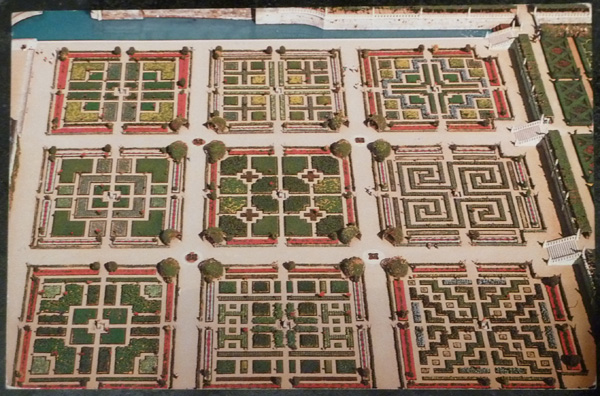

The last part of our cheese junket wasn’t another cheesemaker or farm— it was the Dane County Farmer’s Market held each Saturday around the capitol square. I’d always heard it was bigger and better than any of our Chicago markets, much as I love them. But I never realized how much bigger— any one side of the capitol square would make an exceptional market in Chicago, it was the first market that ever exhausted me before I exhausted it. We saw many of the cheesemakers we’d met or tried there, as well as an astounding array of produce vendors, sausage makers, bakers, doughnut makers, everything. It was really a revelation.

Trisha, a chef in our tour group, worked this day at L’Etoile, proving they really do shop the market as she pulled the official L’Etoile little red wagon.

Hook’s table, with easily 30 cheeses to sample.

Hammond buys cheese from Willi Lehner.

* * *

More posts from other folks on this trip:

Driftless Appetite: The New Rock and Roll

Madame Fromage: Otter Creek

And Cooking With Amy, hilariously, zeroed in on the same monster kohlrabi I did.

I will update this further as I spot stuff…

Posted in

Posted in