My sons have done 4H for three years. This despite the fact that we live in the heart of Chicago, which always prompts a chuckle from the auctioneer at the Lake County Fair when we show our lamb (“Not sure what kinda farms they got in Chee-cawger”). But they fell in love with the idea of raising an animal and winning ribbons for it many years ago, and as participants in the 4H program at Wagner Farm in Glenview (the last working farm in Cook County, now run by the park district) we have raised, and yes turned over for slaughter, three lambs, Triskaidekaphobia, Arachnophobia, and Ewe2. (Who was neither a ewe nor our second lamb, but the boys had just discovered rock and roll that year.) You can see some of the history of our experiences raising lambs in these videos— and in the accompanying story about protesters at Wagner Farm; not everybody is happy to keep a little piece of agricultural reality alive in Cook County.

This year they’re going to raise a pig. And because this is qualitatively different from raising a lamb, for reasons some of which will begin to be stated below, and the year promises to have several interesting features to it (including one very interesting guest speaker next month), I’ve decided to keep a chronicle here of our adventures with our pig from now until the fair in at the end of July. To read them all, click the “Our Season of Pig” link under Categories at right. Here’s the first one.

Swine Management 101

“Pigs are better. Pigs are smarter than lambs,” one of the girls in my car says.

“A crust of bread is smarter than a lamb,” another girl says.

We’ve driven so far out of Chicago that we’ve reached the point where towns and farmland alternate, the rhythm of passing KFCs and Merlin’s Muffler shops suddenly opening up to the blankness of the night sky. It’s pitch black at 6:45 pm, which means that not only do I not know where I really am, but wherever I am has all kinds of sinister associations from movies; we are one flat tire away from wandering into the wrong abandoned barn on a moonless night and being killed by the Children of the Corn. Add to this the fact that I don’t even have my own children with me, but someone else’s— for reasons of which boys wanted to all go together, and which girls didn’t— and the “what the hell have I gotten myself into” factor is ranking about as high as the time I lost my mountain-biking partner in the Gooseberry Mesa in Utah. (He later designed this blog, so he must have survived.)

Our destination is Woodstock, Illinois, which in daylight looks exactly like its quaint small-town self in the movie Groundhog Day, but at night is a dark void without feature or especially clear road signage. Finally with the help of a couple of phone calls, we find the McHenry County Fairground and I take the last parking space in the front lot, which requires driving my Prius up a mound of snow and leaving it parked nose in the air at an angle, like a pickup truck in an ad. Which is ironic since it’s about the only vehicle in the entire lot that isn’t a pickup truck. I’ve never felt as much of a fraud in 4H as I do at this moment.

We find the door and enter the large hall, which is painted a shade of green last seen on wood-paneled station wagons, and enter under the watchful eyes of past fair queens.

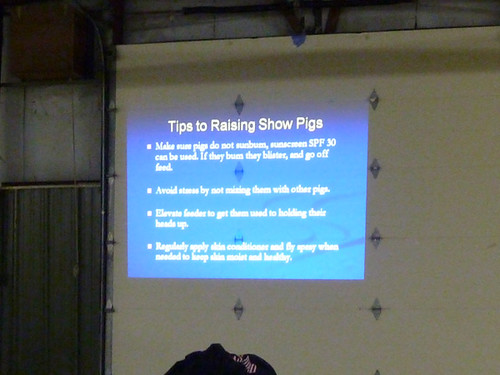

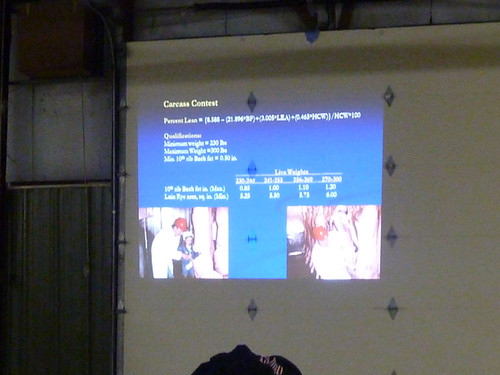

We are here for Swine Management, which is a required annual course for anyone raising a pig to show at the fairs in the state of Illinois. (There’s also an online test in ethics, which is good for life— not necessarily the most effective choice when it’s being mainly taken at the age of 10. This may explain a lot about the pretty awful state of industrial pork production.) The girls in my car, who’ve taken Swine Management before, have helpfully explained that it is the most BORING thing on earth, and the setup— a Powerpoint presentation given by a man with no P.A. system, who surely can only be heard by half the very large room— seems designed to drive home her point. Nevertheless, the 4H kids do much better than I would expect at paying attention to a fairly arcane agribusiness discussion of historical trends in pig design, selecting pigs for maximum profit, and feeding and caring for them in a way that will score highly with the judges and bring a good price at auction. I find it pretty fascinating too, as most glimpses inside an entirely different way of life are.

When I said pig “design,” I wasn’t exaggerating for comic effect. The first part of the talk is devoted to discussing the changes in pig body types over the years, which are something like the changes in cars over the same period— first round and lardy, then long and streamlined, then shorter and boxier, then more sleekly rounded around the shoulders and back legs. People who are put off by the idea of caring for an animal only to have it killed for meat act as if one day you have a pet and the next you have pork chops, but a discussion like this has nothing to do with pets— this is the pig as industrial product from the very start, selected for its efficiency as one interchangeable part in an industrial process.

Except, of course, in 4H it’s not. These are kids, raising one pig apiece, and I have to think my sons will form a closer and potentially more emotionally upsetting bond with this relatively more intelligent and personable animal than with the lambs who, as mammals go, were about as cold and blank as a lizard. 4H is creating modern farmers (in some kids, anyway, probably not in mine) by harkening back to an older way of farming that can’t really exist profitably any more. Like the ethics test, this one early experience of hands-on, personal animal husbandry will have to last a lifetime.

The protesters at Wagner Farm last year imagined that the kids were ignorant of what would ultimately happen with their animals. But when this slide depicting the inspection of hanging carcasses came up on screen, there was only the slightest murmur rippling through some of the younger kids in the crowd. Pigs are business, pigs are meat, and everyone here knows it, no matter how young they are. That’s the first difference between farm kids and city ones.

After the presentation, we went to the McDonald’s across the street, and the kids hungrily scarfed down the epitome of industrial food while talking eagerly of the season of the pig ahead.

Myles, deliberately making his deranged Children of the Corn face.

Posted in

Posted in